South African court dismisses a major lawsuit by 140,000 Zambian women and children against Anglo American for Kabwe lead poisoning. A setback for affected communities enduring the lasting impact of lead contamination.

Recovering a sustainable use of the soil is essential for our future, and that of biodiversity. During his Italian visit in occasion of the Seeds&Chips Global Food Innovation Summit in Milan we talked to Edward Mukiibi, Vice President at Slow Food International and Coordinator of Slow Food Uganda Activities. Mukiibi is an agronomist born and raised

Recovering a sustainable use of the soil is essential for our future, and that of biodiversity. During his Italian visit in occasion of the Seeds&Chips Global Food Innovation Summit in Milan we talked to Edward Mukiibi, Vice President at Slow Food International and Coordinator of Slow Food Uganda Activities. Mukiibi is an agronomist born and raised in Uganda, where he works with farming communities and young people to revitalise traditional farming techniques to face the challenges ahead. Indeed, his mission is to defend and promote African biodiversity. Here’s what he told us.

Read more: Sam Kass, the ex-White House chef talks about his fight to make healthy food accessible to all

Going back to the soil (and to a sustainable use of it) is key to the future of people and biodiversity. What is the People4Soil petition you’re supporting at Slow Food and why is it crucial?

Soil is a living thing. It is home to a lot of life and biodiversity. I think the moment we stop feeding the soil, we will stop feeding ourselves: we have to feed the soil to feed us. The soil has to be fed, has to be taken care of, we don’t need to pollute it. It is a non-renewable resource and if we continue to pollute it and destroy the soil system and its biodiversity, it will be too late. Soil is the foundation of many civilisations: many people’s lives come from the soil and many communities are being built on it. That’s why we need to protect this non-renewable resource.

Another European Citizens Initiative you’re supporting aims to ban glyphosate. What do you think about this herbicide – which is the most widely used in agriculture?

Glyphosate is widely used but isn’t a necessity in our production systems. It’s a kind of lifestyle that destroys the environment and biodiversity, that creates dependency and also binds many people to the big companies that supply it. It doesn’t only destroys weeds but also other forms of life – like the millions of insects in the soil, the bees, which are one of the most important things that have ever been created on Earth.

Also, it isn’t true that wild plants are useless. Some of the plants that grow by themselves have a lot of advantages for the ecosystem. For example, there are plants in our African traditional farming system we use as soil fatigue indicators: when they grow in your garden you know what the soil is suitable for. In certain communities we don’t have high-tech mapping systems, so small-scale farmers depend on plants. If you have an industrial mono-crop system that uses a lot of glyphosate in the end certain species or types of crop will stop growing.

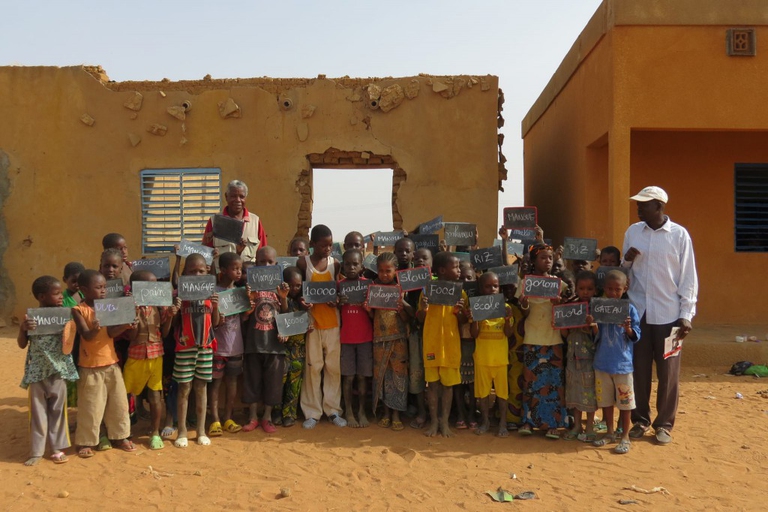

Let’s talk a bit about you. You’re working in African communities and schools with the 10,000 Gardens in Africa project – and with your own project, Developing Innovations in School Cultivation. What are these initiatives about?

The 10,000 Gardens in Africa project is developed by us, the people of Africa, who are supporting the Slow Food philosophy and believe that even Africans deserve access to good, clean and fair food. We came up with this project to revitalise our farming systems which have been there for us and are typically made for or tailored to the harsh African environment.

This project also helps us to preserve our traditional and local knowledge. It helps to reconnect the old generation to the young one because there are women and men who can teach children about local biodiversity, the local farming system, about managing the soil and overcoming drought. This is the knowledge we need to bring down to the new African generation.

Also, Africa being a young continent in terms of demographics, we need to reconnect young people with the land. Many times we lose our lands because there is a claim that people aren’t using the land so they give it to investors from China or anywhere else. In the end, communities lose out. But when we reconnect young people to reduce rural migration, when we reconnect them with land through this project, we’re able to build a community that understands the real value of growing our own food, of using the land we have.

The 10,000 Gardens in Africa project tries to fix all these things. Slow Food raised support for it, helped us extend it to many countries bringing the good news to communities that have lost a lot in their own activities.

The Developing Innovations in School Cultivation project has started to reshape the attitude of young people towards farming. We grew up in a farm with my mother but at school a lot of things made us hate farms. Many schools in Africa use farming as a form punishment. For example, if you don’t speak English but speak your local language instead, you’re sent to a farm for punishment. So we had to create something more positive, more educational, more motivating and more interesting. I came up with this idea, we started working on it by talking to young people to bring them back to the farm. So young people are allowed to work with the land, innovate, come up with different techniques and revisit traditional ones. If you give them space, they become innovators.

I don’t believe in totally creating new things. I believe there are some old traditional practices that are very good and promote agroecology [an approach that adopts a holistic view of agriculture], but we need to revisit or update them to reach present challenges. We’re working in a few schools with this project. We didn’t receive enough funding to scale out but we hope to do so. We need innovations to promote and scale out agroecology. We need people investing in sustainable agriculture, shortening the food chain, producing local plant-based soil additives, working with young people where they raise money and invest.

How can local and sustainable agriculture be the solution in an ever globalised world?

Everyone comes from a local community. So the challenge is on us to rethink and rebuild an economy around us, supporting local farmers, local vendors and farmers markets. This is how we can connect these small dots. Before acting globally we need to start acting locally. I think that we should start by ourselves – by meeting farmers at local markets and giving them feedback about their products. Locally, we have the connection between the consumers and producers. If we connect these dots the global question will be answered. This doesn’t mean we have to stop buying in supermarkets because we also need to talk to big chains to start creating shelves where local farmers can put their products. We need to influence them. It’s a big advocacy job. We need to lobby for this, advocate for this, in order to create this kind of connection. Step by step we can do it.

Siamo anche su WhatsApp. Segui il canale ufficiale LifeGate per restare aggiornata, aggiornato sulle ultime notizie e sulle nostre attività.

![]()

Quest'opera è distribuita con Licenza Creative Commons Attribuzione - Non commerciale - Non opere derivate 4.0 Internazionale.

South African court dismisses a major lawsuit by 140,000 Zambian women and children against Anglo American for Kabwe lead poisoning. A setback for affected communities enduring the lasting impact of lead contamination.

Controversial African land deals by Blue Carbon face skepticism regarding their environmental impact and doubts about the company’s track record, raising concerns about potential divergence from authentic environmental initiatives.

Majuli, the world’s largest river island in Assam State of India is quickly disappearing into the Brahmaputra river due to soil erosion.

Food imported into the EU aren’t subject to the same production standards as European food. The introduction of mirror clauses would ensure reciprocity while also encouraging the agroecological transition.

Sikkim is a hilly State in north-east India. Surrounded by villages that attracts outsiders thanks to its soothing calmness and natural beauty.

Sikkim, one of the smallest states in India has made it mandatory for new mothers to plant saplings and protect them like their children to save environment

Chilekwa Mumba is a Zambian is an environmental activist and community organizer. He is known for having organized a successful lawsuit against UK-based mining companies.

What led to the Fukushima water release, and what are the impacts of one of the most controversial decisions of the post-nuclear disaster clean-up effort?

Nzambi Matee is a Kenyan engineer who produces sustainable low-cost construction materials made of recycled plastic waste with the aim of addressing plastic pollution and affordable housing.