The Louise Michel is the humanitarian rescue ship saving lives in the Mediterranean. Financed by the artist Banksy, it has found a safe port in Sicily.

Travelling across the new route used by migrants to cross the Balkans and reach Trieste in Italy, a reportage that documents the social, economic and political changes of the countries along the way.

The wind blows in Trieste, like in the best clichés. “The weather will be good tomorrow,” Paola says. She’s from Trieste and has been living in Bosnia Herzegovina for 15 years. The imposing Habsburg-era port is next to the train station. Some buildings were renovated, like warehouse 26, which was added to the museum unit, whilst others have been left neglected over time. Some migrants are taking shelter in a silo inside a building near the arrival and departure railway tracks. A young afghan man, no older than 20 years old, isn’t happy about strangers or journalists entering the area: “What do you want? Do you want an interview? Do you want a scoop?”. Four shacks built with scraps, hidden from passersby’s gaze, Trieste is one of the stops in the long journey. A “waiting room” before heading to Germany, France, Northern Europe and other Italian cities.

A thirteen-day walk following the tracks of migrants: 180 kilometres south the wind has disappeared, the language spoken is Serbian-Croatian, the nation is Bosnia. Bihac and Velika Kladusa, facing the south-eastern Croatian border, two cities where migrants stop to rest. Thick forests surround the suburbs and the border is a few hours away. “I want to go to Spain, I want to be a nurse”, “Germany, yes, Germany, I can have many jobs there”, “I have friends in Brescia, we’ll see from there”: they’re from Pakistan and Afghanistan, they’ve crossed Iran, Turkey, Greece, Macedonia, Serbia and reach the former student dormitory in Bihac, the base camp, before leaving once again.

The rigid Balkan winter is coming. Migrant parties leave for the woods every day. A little more than 13,000 people have chosen to pass through Bosnia on route towards the West this year. The numbers are official, provided by the International Organisation for Migration (IOM), but trafficking causes a quiet chaos with regards to the figures. “We think the numbers are 15 per cent higher than those registered”: Peter van der Auweraert, IOM coordinator for the Western Balkans, confirms the difficulty in understanding the actual magnitude of the phenomenon.

The simplest border to cross out of the three is the one between Bosnia and Croatia, lined by hundreds of kilometres of forest. It’s the former frontline of the Bosnian war. “They pass through here, I can hear them talk in Serbian-Croatian. They say: ‘there’s police there, you can’t get through’,” Amir, a 70-year-old man from Bihac, suggests that migrants are helped by locals when they move on the tracks towards the border. “I retired 20 years ago, my wife ten years ago. We built a nice house in the forest with our money, I found my door open many times and it was often damaged – he goes on –. I’m saying: you’re welcome if you need water, food and a bed, but I don’t know what my reaction could be if you behave like this”. Bosnian civilians really do own weapons, a heritage of the war. According to the Small Arms Survey, published on the 18th of June, there are 31 firearms every 100 inhabitants. “I protected this house for four years and now I have to continue doing so in times of peace, I don’t know, I invested money here, I’ll protect my things,” Amir concludes.

There’s a latent contradiction in locals’ statements. One the one hand, the memory of having to escape and being considered “migrants” themselves remains just below the surface. If anger caused by isolated destructive behaviours endangers coexistence the memories are what keeps everything together, avoiding conflict.

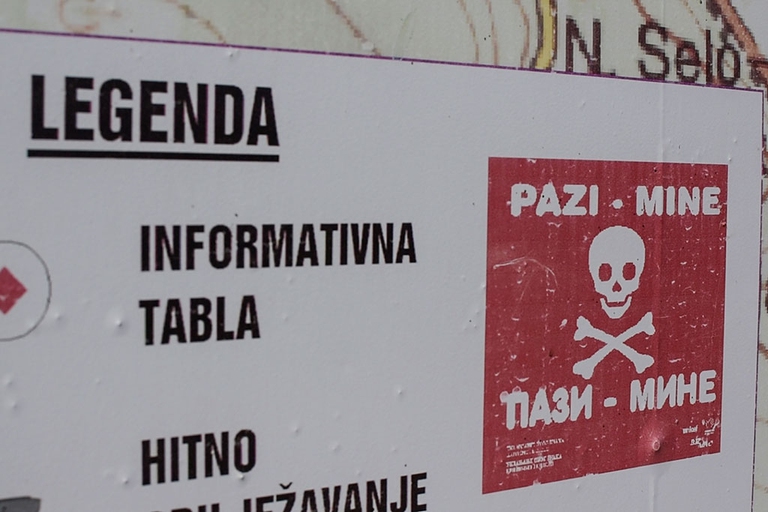

After passing the mines that infest the border and the threat of wild animals, we enter Croatia, which is probably the most dangerous part of the journey. The stories of violence by border police are a consolidated memory for the more experienced people, and a ghost for the others at their first attempts. Avoid Karlovac and other urban areas, follow hidden tracks or change clothes to blend in and take buses that get close to Slovenia. Even the locals can be a problem: “They call the police as soon as they see us, and they come here and arrest us in 10 minutes,” Hassan, 20 years old, from Pakistan tells us. You’re lucky if they think you’re a tourist.

The Kolpa is the natural border that separates Croatia and Slovenia. A breath-taking view as green hills meet the water, whilst groups of foreigners get ready for rafting. The Ljubljana government began erecting a barrier on the river in 2015. Barbed wire, nets, fences and locks to stop the flow of migrants entering the country. One of the many border crossings is in Kupi: the bridge, customs, two offices and you’re in the Schengen area. “It wasn’t us, you’ve got to ask them,” a policeman pointing to his Slovenian colleague tells us. “We have nothing to say about the migrants that get through, you should speak to our superiors in Ljubljana,” the Slovenian officer replies.

The Kolpa runs across the path towards the East. The barrier is without interruptions, separating the road from the water. “The river is dangerous if you don’t know it well. Some migrants have died trying to cross it,” Paola explains. The Kolpa is placid, but the cold and currents are real threats, especially on rainy days: one of the waiters who works in a restaurant along the road tells us, “yes, I’ve seen migrants cross the river, we helped them. I even heard of some children who died in the north”.

Ljuba lives with her husband in Fara, a small town on the shores of the Kolpa. The couple manages a bed and breakfast immersed in nature. “Seeing this fence makes my heart ache,” she says showing us the access points to the river blocked with closed locks, “a few months ago they came with bulldozers and erected this fence. They changed our lives and our relationship with the river without even asking”. There’s anger and frustration in Ljuba’s words. She lives with the beauty of this place and pureness of the Kolpa day to day. “Their only achievement was trapping us. They didn’t stop the migrants from crossing, but the access for locals and tourists that is the basis of our livelihood is blocked,” she concludes. “We think this is the government’s fault – Valentin, Ljuba’s husband who was also the mayor of Kostel, says –. I was born here, what could this barrier possibly mean to me? It complicates and separates relationships between people and damages the interaction with the other side of the river”.

After a two-hour drive and 150 kilometres to the west we reach Capodistria, perched on the homonymous gulf. The port city is one of the points from which migrants access Italy. “Of course I’ve driven migrants to Italy, what should I do? Ask them for identification? I’m not a policeman, they’re clients, they ask me to go to Trieste, just like you, should I refuse?,” the taxi driver who is taking us to Trieste tells us. After a 20 minutes drive we can see the marvellous Unità Square in Trieste, we’re already in Italy. The Ministry of the Interior has intensified checks at border crossings since the beginning of this past summer, including deploying police departments from the city of Padua and modern technologies in order to identify license plates. As Paola returns towards the centre of Trieste, she says: “As you can see, two out of three crossings are totally unguarded and even if they wanted to supervise every single road that brings to Italy, the terrestrial boundary is unmanageable, too many kilometres and too many forests”.

Laura and Michele live in a residential neighbourhood in Trieste, on the first floor. In the last few weeks, they decided to help two groups of Iranians who were struggling to cross from Bosnia to Italy. “Ignoring this reality would mean looking the other way, getting used to the screams that come from the other side of the border would be the death of culture, civilisation and humanity,” Michele says. The couple from Trieste specifies that in the last few weeks they’ve only helped people they already knew. “It seems cynical, but we had personal relationships with some of these people, and when someone you know needs a hand, you can’t hide,” Laura concludes.

Reza is sitting in the living room between the bookshelf and framed photos. “I was scared on the thirteenth day of our journey. The rain had soaked all my clothes. Without Laura and Michele’s help I would’ve never made it to Italy”. Reza is now in Germany, his original destination. “They caught me 16 times, in Croatia and Slovenia, they beat me but as you can see, now I’m where I want to be,” Reza writes in a chat.

On the 17th of September in Sochi, Russian president Vladimir Putin and his Turkish counterpart Recep Tayyip Erdogan agreed on the institution of a demilitarised zone in the town of Idlib, in Syria, temporarily avoiding an offensive that could’ve caused another humanitarian emergency and a new flow of refugees towards Turkey and Europe. If 2018 was year zero for the “new” route through Bosnia, possible geopolitical changes in the near future – not only in Syria – would give way to an unstoppable phenomenon. When faced with the facts, even with the deterrent of violent expulsions, which have yet to be officially confirmed, the border is still full of holes. Bosnia’s stability will be on the line in 2019, a country that stands on uncertain legs but more generally speaking, the European Union and its ability to keep borders safe will be under scrutiny, a predominant political issue in the three countries affected by the new route: Croatia, Slovenia and Italy.

Siamo anche su WhatsApp. Segui il canale ufficiale LifeGate per restare aggiornata, aggiornato sulle ultime notizie e sulle nostre attività.

![]()

Quest'opera è distribuita con Licenza Creative Commons Attribuzione - Non commerciale - Non opere derivate 4.0 Internazionale.

The Louise Michel is the humanitarian rescue ship saving lives in the Mediterranean. Financed by the artist Banksy, it has found a safe port in Sicily.

Venezuelan refugees are vulnerable to the worsening outbreak in South America: while coronavirus doesn’t discriminate, it does affect some people more than others.

In the midst of India’s coronavirus lockdown, two dozen people lost their lives in a desperate bid to return home: migrant labourers forced to leave the cities where they worked once starvation began knocking at their doors.

Behrouz Boochani returned to being a free man during the course of this interview. The Kurdish writer was imprisoned by the Australian government in Papua New Guinea for six years.

The Global Compact for Safe, Orderly and Regular Migration was signed by 164 nations in Marrakech. This is what the non-binding agreement that encourages international cooperation stipulates.

The winners of the World Press Photo 2019 tell the stories of migrants in the Americas. From the iconic image of a girl crying on the border between Mexico and the United States to the thousands of people walking from Honduras towards a better life.

The Semìno project is a journey of discovery through different countries’ food habits, offering migrants employment opportunities and allowing us to enjoy the properties of vegetables from all over the world.

The countries hosting the most refugees aren’t the wealthy, Western ones. An overview by NGO Action Against Hunger reminds us that refugees and internally displaced people are far from being safe.

The solar plant in Jordan’s Azraq refugee camp has started to produce energy, allowing Syrian refugees in the camp to have electricity in their tents. It’s the world’s first refugee camp to be powered by renewable energy: a 2MW plant managed by the UNHCR and financed thanks to the Brighter Lives for Refugees campaign launched