The climate impact of the U.S. Gulf of Mexico’s oil and gas production could be higher than government inventories indicate.

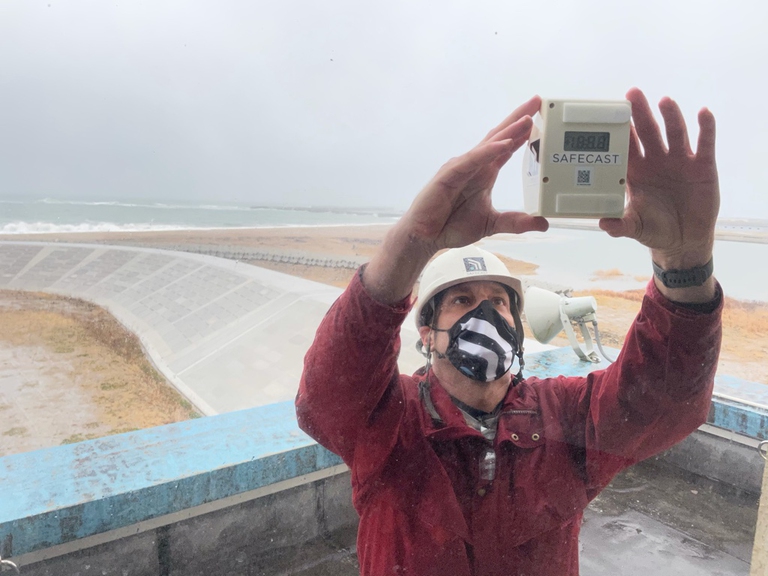

“None of the information from the government and TEPCO should be trusted unless it’s independently verified,” says Safecast’s Azby Brown. We discuss what lies behind Japan’s decision to release radioactive water into the ocean with the researcher and transparency advocate.

The announcement came on 13th April. The Japanese government said it had officially decided to release over one million tonnes of treated radioactive water into the Pacific Ocean starting in two years’ time. The water, currently stored in tanks on land, is used to cool the Fukushima Daiichi nuclear power plant’s reactors. The plant is in the throes of a complex decommissioning process following the intense damage it suffered as a result of the earthquake and tsunami that hit Japan on 11th March 2011. The decision to release the contaminated water was met with strong opposition from environmental groups, which lament the risk to human health posed by radionuclides such as carbon-14, local fisheries cooperatives, who fear reputational damage due to the presence of tritium (another radionuclide) in the water, and neighbours South Korea and China.

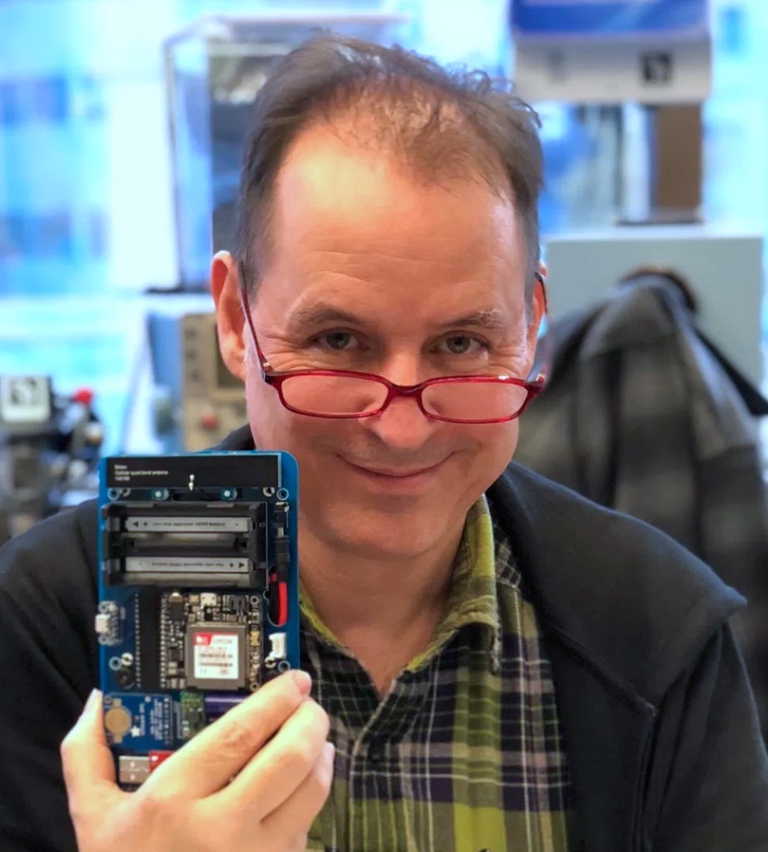

“We feel the decision was made years ago,” says Azby Brown, lead researcher at environmental monitoring organisation Safecast. Brown’s background is in architecture and art, and in 2003 he founded the KIT Future Design Institute, an independent research laboratory in Tokyo that closed in 2017. When the earthquake, tsunami and nuclear “triple disaster” hit Japan – where Brown has lived since 1985 –, he became involved with Safecast, a non-profit that began monitoring, collecting and openly sharing information on environmental radiation in the aftermath of the calamity.

Safecast has since expanded its reach, openly sharing data on radiation as well as air quality collected mainly by volunteers all over the world. When it comes to understanding the consequences of the Fukushima nuclear accident, it has become a key source of reliable and independent information. In the ten years since the disaster, Brown, together with Safecast, has been advocating for better knowledge and transparency in dealing with the disaster’s fallout. In conversation with him, we try to understand why the Japanese government has decided to go ahead with the release of treated radioactive water even in the face of such vociferous opposition.

Should we be worried about the release of contaminated water from Fukushima Daiichi?

It’s all conditional on whether TEPCO (the Tokyo Electric Power Company, which owns Fukushima Daiichi and is responsible for its decommissioning, ed.) is able to get rid of the other radionuclides besides tritium and even carbon-14, dilute the water and release it little by little over many years like they say they’re going to do. If so, I don’t think we would have much concern in terms of health risks – it’s not that there’s no risk, but it would be pretty small. But given these caveats, there are things we need to know more about.

Off the French coast, the La Hague nuclear fuel processing plant has been constantly releasing tritium for decades. There’s a lot of monitoring of water, marine life and terrestrial environments. The monitoring programmes are pretty transparent and also include citizens’ groups such as ACRO. Even organisations like the French Institute for Radiological Protection and Nuclear Safety, which has some of the best research on this, says that we still don’t know enough about organically bound tritium, which is a component of the tritium being released.

I don’t think we need to be worried or stop eating fish or anything like that, but we need to keep an eye on whether (the Japanese government and TEPCO) will do what they say they’re going to do. Overall, it’s a large amount of tritium and there are still a lot of other radionuclides in the water, including strontium-90, ruthenium-106, iodine-129 and cobalt-60. And TEPCO has such a bad record of transparency, including disseminating false and deceptive information. Even if you might say that the tritium won’t be much, there’s enough strontium-90 that would be a real concern. That bioaccumulates, has a long half-life, and would go into the fish and seabed. This is something we need to be concerned about, to make sure it doesn’t happen.

You’ve recently written about how the water release could set a dangerous international precedent. In what way?

In 2011 there was the precedent of the release of quite a lot of contaminated water from Fukushima Daiichi in order to make room for even more highly radioactive water. There are international treaties and International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) guidelines that stipulate things that should happen before, during and after any kind of transboundary release of nuclear material. But none of these treaties and agreements are binding or specifically say that you can’t release water into the ocean from a source that’s on the land. This is a big problem. Our greater concern is the precedent that this could set for even less transparent and habitually worse offenders.

Quite a few nuclear power nations could be tempted to defy opposition from their neighbours and release radioactive material to the ocean freely, using the Fukushima example as a precedent. What is to prevent the Russian Federation from unilaterally releasing radioactive liquid waste into the Arctic Ocean or the Sea of Japan? Or China into the Sea of Japan or the South China Sea? Or the United Arab Emirates to the Persian Gulf?

How would you describe the relationship between TEPCO and the government?

The Japanese government is TEPCO’s major shareholder. Over the years, the Japanese Nuclear Regulation Authority has pressured TEPCO many times, but they’ve also recommended TEPCO to dilute the water and release it. The government has supported this plan since the beginning. We’ve characterised it as a kind of kabuki dance (“political theatre,” ed.). When TEPCO is asked whether it wants to release the water, it answers that it’s up to the government. And the IAEA has also recommended it. So, TEPCO and the government both say the IAEA says it’s the thing to do.

We’ve been following this issue since the beginning and are constantly pointing out problems of transparency and communication, including in the way policies are set and decisions are made. Even in this case, it’s not really clear who made the decision. Maybe it was Japan’s Prime Minister Yoshihide Suga, ultimately. He’s hitched his wagon to this.

You’ve pointed out TEPCO’s lack of transparency. Can we trust the Japanese government instead?

There’s no environmentally clean solution to this problem. It’s about what’s going to be the least bad: and maybe there’s a strong argument that diluting and releasing the water is the least objectionable. People like Ken Buesseler of Woods Hole Oceanographic Institute (in the United States, ed.) believe they should first keep the water in tanks for 60 years or so, so that radioactivity declines significantly. The government says it investigated storing it long-term in stronger tanks (and therefore less susceptible to the risks posed by natural disasters, ed.) but I’m not convinced they examined the possibility thoroughly. There’s no detailed investigative report.

Here you get into government bureaucracy dynamics, where nobody has any incentive to do more than they were ordered to do. With the water issue, I think it was decided years ago. It was a done deal and they tried to shape public opinion to accept it.

In terms of trust, back in 2018 I was talking to people at TEPCO, the government, fisheries and other researchers. I especially wanted to know what was in the water besides tritium. I asked TEPCO engineers, and they gave me data that showed only tritium. In September that year, it became known that the water treatment system (the ALPS radionuclide removal system, ed.) wasn’t working well, especially at the beginning, and there were a lot of other radionuclides in the tank-stored water (including above-limit levels of strontium-90, cobalt-60 and ruthenium-106, as Brown points out in a recent commentary, ed.). I was really angry. I’d asked them nicely, kindly, directly several times and every time they’d lied to me.

Why did they lie? Who made them? Who was trying to keep that information from becoming public? I just don’t know, to this point. The misinformation comes from high up and the communicators have to decide what their responsibility is when they realise that they’re being lied to by their bosses. None of the information from the government and Tepco should be trusted unless it’s independently verified.

The ALPS system does, in fact, appear capable of removing all radionuclides of concern except tritium and carbon-14 when operating at top condition, but it’s dangerous to assume that all 1.2 million tonnes of water currently being stored, as well as the similarly large additional quantity expected to be generated, will be effectively treated to the required rigorous standard without fail over the course of decades.

What about the government and TEPCO’s competency in dealing with the issue of the radioactive water?

We should continue to be sceptical of the government’s and TEPCO’s competency to do this stuff well. So much of Japanese government communication is intended to camouflage a lack of competency. They don’t want to make promises that can be politically painful later, so they make vague ones: “We’ll do our best do reduce these risks as quickly as we can, such as to get the additional radiation dose rate in Fukushima down to 1 millisievert per year”. Where’s the plan? Show us the plan. The real concerns of the people come last.

The decision to release the water has been made in the face of strong opposition. In what way has it been “unilateral,” as you’ve described it?

Who does the government consider stakeholders? Stakeholders should be defined very broadly, inclusively and internationally. The language is there in the agreements, etcetera, but it still isn’t binding. In Japan, the fisheries cooperatives have been considered a major stakeholder. There have been releases of water from Fukushima Daiichi over the years from two specific sources. One is the bypass, wells uphill of the reactors that capture groundwater before it reaches the reactor area. That water is treated, tested and if it’s okay, it can be released. Then there are the subdrain wells surrounding the reactors. The fisheries cooperatives agreed that they wouldn’t protest release from these sources if there was testing by third parties. So, they’re not against water being released, but it’s this water that will be released (starting in two years’ time, ed.) that contains a specific contaminant that they’re concerned about because of what the public thinks and how it’s going to affect their market.

You have to involve people in the process of evaluation, so they can decide whether or not they want to accept it. Safecast’s position is that people are free to reject it even for reasons that may not seem scientific. In this case, the fisheries were so strongly against the water release, and then the government made the decision anyway. And then what happened? The IAEA said it’s fine and the United States government agreed. Japan can now say the decision wasn’t unilateral.

Considering that the government wants to restart other nuclear reactors in Japan, would you say that the country’s anti-nuclear movement, which gained significant momentum in the aftermath of the 2011 disaster, ultimately failed?

Even if a majority of the population opposes nuclear power, this stance doesn’t get translated into energy policy. There was so much soul searching after the disaster… but almost nothing changed in a big picture way. However, a lot has changed at the grassroots level. There are pretty vigorous environmental networks in Japan and lots of alternative things being tried in the areas of food, energy, forestry or water. Concerning the nuclear restarts, it’s worth nothing that many prefectural and local governments are prepared to oppose the central government by blocking them.

Returning to the release of water from Fukushima Daiichi, you’ve indicated the need for a “robust impact assessment and verification process”. How close or far are we from this being achieved?

Very far in terms of an impact assessment, at the moment. In recent documents, there’s mention of what (the government and TEPCO) consider an impact assessment, which is actually a dispersal model: they modelled where the tritium would go in the ocean – note that they’re only assuming tritium. That’s not a full assessment, it’s simply a dispersal model. The IAEA published a report last year pointing out that they hoped to see more complete environmental assessments. It would’ve been easy for the IAEA director, when he made his announcement after the water release plan was officially announced, to say that they’re prepared to support the plan once they’ve seen a full environmental assessment. Why don’t they do that? Because there is none.

We believe that fully transparent independent monitoring and oversight of the environment must be done prior to, during and after any such release to ensure that the process is acceptable to the global community.

In terms of the monitoring, the IAEA – which is an international body that has its own networks and laboratories – said that they’re going to be involved. I’m saying, open it up to everybody: independent researchers, groups in Japan and elsewhere. The monitoring data needs to be timely and open. They should’ve started setting this up years ago, because no matter what they were going to do, they were going to need environmental assessments and inclusive monitoring.

They have about two years now to set it up, and the first challenge is going to be to persuade the IAEA, Japanese government and other governments that this needs to be done. People not just in countries on the Pacific Rim, but other ones too, can request their government to demand to be a part of this process.

Siamo anche su WhatsApp. Segui il canale ufficiale LifeGate per restare aggiornata, aggiornato sulle ultime notizie e sulle nostre attività.

![]()

Quest'opera è distribuita con Licenza Creative Commons Attribuzione - Non commerciale - Non opere derivate 4.0 Internazionale.

The climate impact of the U.S. Gulf of Mexico’s oil and gas production could be higher than government inventories indicate.

ReconAfrica hunt for oil and gas threatens vital waterways home to the world’s largest elephant population and endangered wildlife

Despite environmental warnings, the Tanzanian government is set to build a dam in the heart of the Selous Game Reserve, a UNESCO World Heritage site.

Researchers from the IFM at Deakin University in Victoria, Australia have tested a novel method for removing silicon from used solar panels.

The Congolese government is allowing energy firms to bid for access to its vast oil and gas reserves, risking terrible ecological and climate effects.

The US government has approved ConocoPhillips’s controversial Willow Project to drill for oil in Alaska’s National Petroleum Reserve.

Environmental activists say the EACOP pipeline will damage Uganda’s iconic fragile ecosystem and the livelihoods of tens of thousands of people.

The EU has banned the sale of new petrol and diesel cars and vans from 2035. From then on, new cars and vans sold in the EU must run on other fuels.

Environmental activists have accused Eskom of emitting toxic chemicals that are costing thousands of lives and changing rainfall patterns.