Kyoto’s premier photography festival, Kyotographie, grows in stature with the launch of a new music festival, Kyotophonie, held in the spring and autumn.

Survival, multiculturalism, plastic islands. Musician Grey Filastine recounts his adventure aboard the Arka Kinari, which set sail in 2019 and spent much of last year adrift in the Pacific because of the pandemic.

Unlike most artists who have made a commitment to environmental rights often merely for publicity, Filastine & Nova have made this their existential calling. The duo spent years decrying social injustice and the climate crisis through experimental music and performances in extreme locations, like Java’s sulfur mines or the Calais Jungle. Now, US producer Grey Filastine and Indonesian singer Nova Ruth have left it all behind in pursuit of a dream: to set sail across the world, creating travelling shows, without causing pollution.

As a teenager, Filastine was part of Seattle’s radical environmentalist group Earth First!, and later took part in anti-globalisation protests as a percussionist for the Infernal Noise Brigade. After experiences in Northern Africa, Turkey, Europe, and Asia, Filastine met Nova in 2008, during a tour headed for Australia. The couple, both activists and artists, have never been apart since, except for visa or green card reasons. They’ve shared stages and life experiences alike. In 2019, the pair sold their home, took out a loan, and launched a crowdfunding campaign so that they could buy and restore a sailing ship. In Rotterdam, they found a 23-metre schooner that was originally built in 1947. This vessel was structurally and aesthetically similar to their ideal ship, the traditional Indonesian Pinisi, which Nova’s ancestors from the Bugis ethnic group used to sail in.

The ship was renamed Arka Kinari, from the Latin verb arcere, meaning “to hold off or defend”, and from the Sanskrit kimnara, a half-human, half-bird musician, guardian of the tree of life. It was conceived as a return to slow touring, a “subversive, immersive and partially submerged” platform from which to raise the eco-alarm, living a nomadic life in an ever more porous, borderless future. Powered by renewable energy, Arka Kinari also functions as a stage for live music and multimedia performances, with images projected onto the sails. The message is about the possibility of a decarbonised world, resilient in the face of climate change, and committed to protecting the last true commons: the sea.

Equipped with solar panels and a seawater desalination system, Arka Kinari set sail from Rotterdam port in September 2019, headed for Indonesia. The crew, in addition to Filastine and Nova, counts seven members from various countries, including the UK, US, France, and Portugal. This close-knit, multicultural team was forced to break apart during the journey because of the pandemic. Arka Kinari’s route, designed to avoid Somali pirates and the war in Yemen, involved crossing the Atlantic, passing by the Canary Islands, Panama and Mexico. A performance was scheduled for each of these three stops.

At the end of February 2020, Nova had to fly back to Indonesia from Mexico to try to arrange papers for the crew’s arrival by sea, a more complex task than had been anticipated. Meanwhile, Arka Kinari began its journey across the Pacific, heading towards Hawaii. The crew were already aware of Covid-19, but they had no idea that over the coming months every country and island in the world would be closing its borders. The global lockdown was especially troubling for the multi-national Arka Kinari crew.

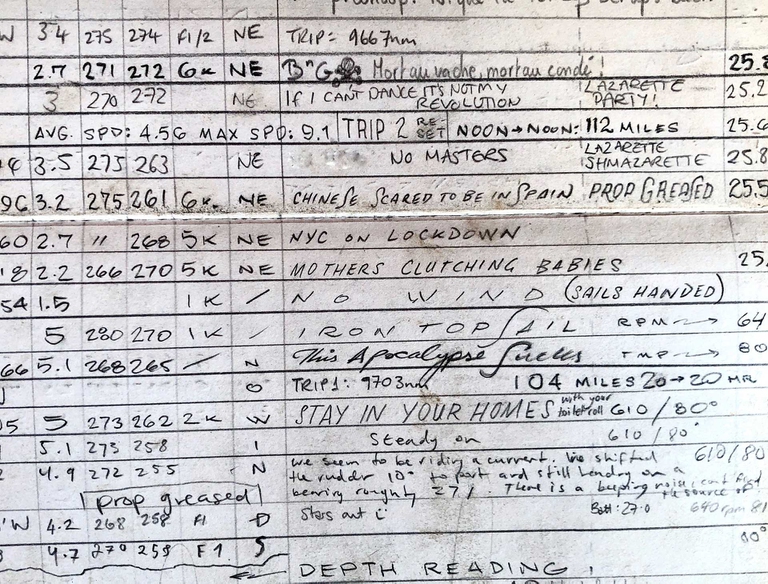

For four months, between March and June, the ship was stuck at sea, and wasn’t allowed to land anywhere. Despite much negotiation, it was denied access to Hawaii, the Marshall Islands, Kiribati, Palau and all of Micronesia’s islands. The crew received no response from the Johnston Atoll and other more-or-less deserted sites used by the US as nuclear testing sites and chemical dumping grounds. Food supplies were beginning to dwindle, fishing wasn’t consistent and typhoon season was fast approaching. It was a race against time. Turning back was impossible, the winds and currents unfavourable. Filastine and his companions faced lonely day after lonely day, in survival mode, clinging to hope, slow satellite connections and an iPhone, after the failure of the ship’s navigation system.

On 30th June, Arka Kinari was finally given permission to land in Guam, part of the Mariana archipelago, a US territory. The crew stayed there for 40 days. Over the following two months, the journey continued, passing through Sorong, in Papua New Guinea, and ending in Bali, where it had to be interrupted for the rainy season. We took this opportunity to interview Grey Filastine about their adventure.

How did you and Nova come up with the Arka Kinari project?

Through our last album and performance, called Drapetomania: An Emergency Exit from the Anthropocene. Arka Kinari is that emergency exit. It’s also our exit from the commercial structures of the music industry, which were never a good fit for our art or ambitions. We struck on the idea of touring by ship partly through the romance of the sea and partly through the cold calculations of an engineer. It’s our answer to the question: how can touring performers move their work around the world without consuming so much fossil fuel? We wanted to do something bold and symbolic, but also practical and real. Basically, to match our method to our message.

To what extent has the pandemic affected the project?

When the pandemic was declared nearly all of the world’s borders were closed, restricting all movement. Almost everyone was locked inside a country, inside their homes. But the pandemic caught us mid-Pacific, so we ended up locked outside of civilisation. The six months that followed were challenging and insecure for everyone, but also unique, spent moving as slowly as possible across the ocean and searching for uninhabited islands.

Incredible…

It might sound idyllic, and at times it was, but at other times it was risky and frightening. We were finally allowed to enter Indonesia after months of negotiations by the Indonesia-based team. Arka Kinari was built as an example project of resilience and alternative methods to tour culture in a transformed world, but we didn’t know it would happen so soon. We’ve accidentally built a project that can actually continue to tour and perform even during these new circumstances. We’re a tiny quarantined world that doesn’t need to pass through airports, petrol stations, taxis or buses. And we perform for audiences in outdoor ports, where there’s plenty of space for social distancing. So, for us just like everyone else, the pandemic has been costly, difficult and dangerous, but it came with a strange twist at the end: unlike everyone else we still have mobility and can actually fulfil our mission.

You’re now settled in Bali. What are the happiest and worst moments you experienced during this one-year adventure?

Bali isn’t our destination, just a pause during the rainy season. Being located near the centre of the archipelago, it’s the easiest place to do repairs and crew changes. Arka Kinari really heightens the dynamic range of life: the low moments are worse than anything I’d ever experienced, and the same for the highs. The worst moments are easy to identify but still hard for me to speak about. Real disasters are only cooked with a complex set of ingredients, so I’m taking my time to write the tales. They’ll probably take the form of a podcast series. But I can share some of our “simpler” challenges: a storm in the Bay of Biscay, early in the voyage, badly damaged the ship and my confidence; a container ship in Colombia nearly ran us over; the Mexican customs agency almost seized the ship; we were refused assistance or re-provisioning by a number of island nations in the Pacific. The happiest moments aren’t so easy to name. It should be the hero’s welcome we received in Indonesia, which literally included red carpets, processions of dancers and drums, flower petals strewn along our path. But those kinds of high-intensity ceremonial moments are always more surreal (or hyperreal) than happy. Happiness comes in subtle ways. I think for all of us on the long Pacific crossing happiness often came on our solo night watches. Every night we each have a two-hour shift alone with the stars, the moon, the sparkling bioluminescence generated by our bow wave, the wind, the temperatures. It’s like a full sensory ASMR, and it’s the best possible moment to listen to music, or simply to think.

How much plastic waste did you see throughout the Atlantic and the Pacific Oceans, even in the most remote islands?

Sadly, I can confirm that the rumours are true. The most remote islands on Earth are littered with plastic debris. These objects are rendered more freakish and surreal by the lack of context: a single Croc shoe, a sun-deformed doll head, rainbows shapes on bright bottle caps. There was so much random trash on these islands that we made a pastime of arranging it into patterns, making pollution art. Our ship isn’t big enough to haul all that trash back to civilisation, and there’s no place for it to go anyway. By design, our route avoided the major gyres, these convergence zones of plastics in the high seas, but we did sail through a gyre in the doldrums just north of the equator. It was an enormous soup of trash, which took us about half a day to get through.

What should humans do to survive the disasters of climate change?

Ideally, we humans would abandon the extractivist model, reduce consumption and slowly draw down our numbers. This is unlikely since we love to buy shit and make babies. The next best plan is resiliency. Not individual “survivalist” resiliency, but constructing cultures of resiliency based on solidarity. If anything, the pandemic should have taught us that mere survival isn’t enough, we need to thrive to make life worth living – and we don’t thrive alone.

Which are the most effective green energies now and in the near future?

The technology is out there and the possibilities are well documented. But it’s not as simple as changing our personal consumer lifestyle choices or installing solar panels on our rooftops. These are honourable things to do, and they set good examples, but ultimately we can’t unfuck the situation without deep systemic change. To use a tech metaphor, we’re living inside a dysfunctional operating system: patches and updates might be helpful to muddle through in the short term, but ultimately we must rip out the bad code at the root. Many would name this shitty operating system capitalism, but the root of the problem is much older and deeper. It emerges with the idea of human exceptionalism – our god complex – when we shifted from being a part of nature to believing that we’re lords and all else exists to serve us.

What are the differences between the anti-globalisation protest movements at the end of the 1990s and those of today, like Greta Thunberg, Fridays For Future or Black Lives Matter?

In between these we also had the massive global movement of 2011, which included linked and mutually inspired uprisings like the Arab Spring, 15M, Occupy Wall Street, Greece, Turkey, Brazil and beyond. Global protest movements are like the cicada, going underground for a period of dormancy then emerging once a decade to make a lot of fucking noise. It’s a noise that bends the arc of history towards justice, but it’s slow and piecemeal work, each generation giving it 100 per cent, taking risks and making sacrifices for tiny incremental gains. But there’s a dangerous counter-attack underway, we’re living on the edge of falling into a new dark age with populists and religious extremists on the rise.

Is living for a long time in a limited space and with an international team a sort of small-scale experiment of a globalised world?

We leftists like to insist that a diverse cultural mix is always better, but the truth is that there are advantages and disadvantages to mixing people from different cultures. Shared language and cultural background make many tasks easier and outcomes more predictable. Conversely, a mix of people will have more friction but generate hybrid ways of thinking, new pidgin languages, new food and most importantly, in my line of work, new music. Fascists, the lazy and many older folks prefer the former, I prefer the latter.

Has your perception of the world before and after the pandemic changed, both as a human and as an artist?

Honestly, I’m not very surprised. Anyone tracking the destruction of the natural world should be anticipating food stress, scarcities and mass migrations, but it turns out that a virus was the first big event. But we’re resilient creatures, it seems we can adapt and normalise anything, including being locked in our homes for months. As always, we can react with compassion or with selfishness, and we’ve seen a rise in both responses. This has created an even larger political divide, most visibly in places where people are poorly educated – like the United States. I made an artistic sacrifice to launch Arka Kinari as the logistical and physical work of building such a project has sequestered years of effort which would have gone into producing music or videos, but it seems to have been the right decision.

How much has your taste in music changed during this journey?

Long periods of isolation at sea, plus the mood of the pandemic, have completely transformed my listening. And it seems I’m not alone. Most electronic music and hip hop, or really anything with beats and bravado – basically, anything I would’ve formerly deejayed – is now unlistenable. Pop song structures now sound crass or even naively “pre-covid”. I now crave long-form compositions: classical (Western or Indian), Qawwali, avant-garde and minimalist composers, or noise and ambient music. For me, this raises the question of what I’ll end up making, performing, or DJing in the coming years, and if there will be an audience for whatever strange form that music will take.

What are your plans after the rainy season?

After the rainy season, we’ll resume our mission: touring the performance, giving workshops. 2021 will be entirely in Indonesian waters, but 2022 might see us range out to other countries in the Asia-Pacific. There’s no final destination but, if we ever do make it back to Europe, perhaps we’d end the project in the Mediterranean. That’s when and how I might move back to Barcelona. But that would be years from now.

What lessons have you learned from this experience?

Decelerate. Take the time to do things of quality. Nature has the final say.

Siamo anche su WhatsApp. Segui il canale ufficiale LifeGate per restare aggiornata, aggiornato sulle ultime notizie e sulle nostre attività.

![]()

Quest'opera è distribuita con Licenza Creative Commons Attribuzione - Non commerciale - Non opere derivate 4.0 Internazionale.

Kyoto’s premier photography festival, Kyotographie, grows in stature with the launch of a new music festival, Kyotophonie, held in the spring and autumn.

The small state of Mizoram in northeast India has a thriving handicraft industry, with artisans making a living by selling products made from bamboo.

Many British cultural institutions have ended their relationship with oil giant BP in recent years, thanks to pressure from activists and the public.

Communities across India are celebrating Durga Puja, a festival that stands as an example of the communal unity which is under threat in the country .

Through stories of encounters between humans and animals, Our Wild Calling offers a way out of an age of solitude. We speak to author Richard Louv.

Chinese filmmaker Chloé Zhao made history, becoming the first Asian woman to win an Academy Award as well as a Golden Globe for Best Director for Nomadland.

A list of some of the best films on ethical and sustainable fashion shown at past editions of the Milan Fashion Film Festival.

“For there is always light, if only we’re brave enough to see it”. Meet Amanda Gorman, the young Black poet who capitvated hearts at Biden’s inauguration.

The winner of the 2020 FTP Prize for Sustainable Art, created to highlight the need for environmental awareness in contemporary art, has been announced.