Why is water important? Glossary: instinct and matter

The impact humanity has on water, how water influences our lives, the stories of who is protecting water, and all the useful actions that can change its future. In ten words.

Reading time: 43 min.

“Are we 100 percent sure that we live on planet Earth?” Perhaps, as NASA now calls it, what we inhabit is actually an Ocean World, where the water that covers about three quarters of the surface is a symbiotic element for every living thing.

The vastness of water is one of our planet’s two lungs, producing half of the oxygen in the atmosphere, and is the network of warm currents that regulate the climate. Water is the foam of the waves that swirls around us as we swim, each stroke replicating the formula of an ancient spell and reinforcing the age-old connection of we humans to this vast world, which today is threatened by the climate crisis and pollution. In this respect, the leading question written by philosopher Simone Regazzoni in the opening pages of his essay ‘Ocean’, sounds like an invitation: it is time to really understand things, to call them by their name and to act for positive change.

This is what the glossary of water is for. It is where we translate ten key words for interpreting phenomena such as drought and the current water crisis into clear, comprehensive language. It is also where we listen to the experiences of the people who battle every day for social inclusiveness through water sports or who have regained their mental and physical balance on a surfboard. And lastly, the glossary is a map we can use to try to find our way towards possible solutions for the protection of the marine, ocean, river and lake environment. It starts on 22 March with the word “change” at the centre of World Water Day 2023, and ends on 8 June on World Oceans Day. Welcome to Planet Water.

n. [deriv. to change]. – Changing, changing oneself: change of home, of season, of temperature; to make a change, especially to habits; change in state of bringing together matter. In sociology, social and cultural change, the alteration of mechanisms within the social structure, characterized by changes in cultural symbols, rules of behaviour, social organizations, or value systems.

According to the most recent UN report , in 2020 about 2 billion people were without access to safely managed drinking water and almost half the world’s population lives without access to safely managed sanitation and hand washing hygiene services. Sadly, these numbers look set to increase, compounded by climate change and population growth. Unless action is taken, now.

It is precisely the urgency of accelerating positive change regarding the ongoing water crisis that is the theme of this year’s World Water Day (WWD), celebrated on 22 March every year since 1993. The goal to reach – still very distant – is the one established in Sustainable Development Goal 6 on water and sanitation of 2030 Agenda of the United Nations, in other words to ensure universal access to drinking water, sanitation and hygiene, and to protect water-related ecosystems.

The problem is also relevant to Italy, where the Po River is running dry and the Apennines are without snow. “We need to think about how we can adjust course, make the necessary change, and bring about a cultural shift that will allow us to reconsider the value and importance of water for our Planet, especially in the light of the now clear knowledge that we are losing this precious resource”, explains Stefano Laporta, President of the Italian Institute for Environmental Protection and Research (ISPRA) and of the National System for Environmental Protection (SNPA). “In order to quickly move towards more sustainable management of water resources, it is essential to have a comprehensive overview of the subject. In addition to our role as researchers, at ISPRA we also help to spread awareness and convey correct messages to the public in order to educate them on more sustainable use of water.”

One of the first major steps at the institutional level is the re-establishment of the UN 2023 water conference that will bring together the international community at the United Nations headquarters in New York from 22 to 24 March. This is the Second World Water Conference, an extraordinary event that will be held 45 years after the first conference, which took place in 1977 in Mar del Plata, Argentina.

But government commitment is not enough, what we need is for the community to mobilise. Water has an impact on everyone’s life, we all have to act: institutions, individuals and business.

“The most important thing a company can bring to the table is a mindset. In 2022, we embarked on a journey that will take us to B-Corp certification and Benefit Company status by 2024. We are well aware that no one can change the world on their own, not even a company like ours, which has water in its genetic make-up. By the same token, we know that those who – like us – live inside and for water sports have, by definition, a special relationship with the element of water and a heightened awareness of its importance. Every single sustainability project, if stand-alone, may not have a significant impact, but in the end all the rivers flow into the sea.” This is how Giuseppe Musciacchio, deputy CEO of the arena brand describes the company’s approach to change, distilled in the Planet Water project manifesto: “It is a non-place, where everyone who has an emotional connection to the water element can rediscover themselves. Planet Water is everywhere, but above all it is inside each one of us, because every single person can have a different intimate relationship with water. It is the element where we win, we lose, we train, we relax, or we play and have fun, whether we are young or old.”

One of the main outcomes of the UN 2023 conference on water will be the adoption of voluntary commitments that will be compiled in the Water Action Agenda, created to show the global community the nature of the commitments made and provide an opportunity to monitor progress and impacts over time.

Like the hummingbird, the tiny, tenacious animal that symbolises World Water Day 2023, each of us is called upon to do our part to “put out the fire”. One drop at a time, together.

Choose your actions from the World Water Day list. Here are some:

- Save water: Take shorter showers and don’t let the tap run when brushing your teeth, doing dishes and preparing food. Report water leaks.

- Eat local: Buy local, seasonal food and look for products made with less water.

- Be curious: Find out where your water comes from and how it is shared, and visit a treatment plant to see how your waste is managed.

- Protect nature: Plant a tree or create a raingarden – use natural solutions to reduce the risk of flooding and store water.

- Build pressure: Write to your elected representatives about budgets for improving water at home and abroad.

- Stop polluting: Don’t put food waste, oils, medicines and chemicals down your toilet or drains.

- Clean up: Take part in clean-ups of your local rivers, lakes, wetlands or beaches.

protection

n. [the act of protecting]. Defence, guardianship, preservation of a right or a tangible or moral asset, and their maintenance and regular use and enjoyment, not only by an individual but also by a community.

For Mariasole Bianco it was love at first dive. A wild child forever in the water during holidays in Sardinia with her parents, then a 15-year-old girl bewitched by scuba diving, then a marine biologist, now a leading voice in Italy and abroad for the protection of the marine environment and sustainable development.

We talk to her about the second word in our water glossary – protection. “For me protection means preserving life, and you can’t talk about water without talking about the ocean. Seen from above, it looks like just an endless blanket of blue. But when you dive in, you start to learn about its enchanting creatures (still largely unknown) and its vulnerability”, she explains.

Confronted with oceans that are increasingly polluted by plastic and chemicals, recklessly exploited by fishing and tourism, and whose biodiversity is threatened by oil exploration, the scientist has decided to roll up her sleeves and travel the world to make people realise how extraordinary these bodies of water are. And to shake us out of the inertia that stops us from doing anything. “We don’t talk enough about this apathy that we have to the natural world around us. It’s really a very important step to facilitate this reconnection to the sea, discovering its wonders and learning about them, because it triggers that feeling of belonging and love that then drives us to take action.”

One of her most recent achievements as president of the not-for-profit association Worldrise is the creation of the first local marine conservation area in Italy. 1,300 metres of coastline on the Golfo Aranci, in the north-east of the island of Sardinia, which will finally be preserved.

It’s so important to reconnect to the sea because it triggers that feeling of belonging and love that then drives us to action.

Mariasole Bianco, marine biologist

There are many protected marine and coastal areas, where human activities, such as fishing and tourism, are now regulated to ensure the protection and long-term preservation of nature and its ecosystems “Our insurance policy for the future” is what Ms Bianco calls these. And off the coast? The Wild West still holds sway. Or at least it did until the turning point on 3 March 2023, when an agreement was reached to adopt the landmark Treaty of the High Seas to protect the ocean. The area outside the 200-nautical mile zone (about 370 kilometres) that belongs to no one state, but is subject to the “principle of freedom of the seas” is called the high seas. And every state is free to do what they like in the high seas – fishing, research, crossing it. These areas beyond national jurisdiction cover nearly two-thirds of the world’s oceans but only one per cent of these two thirds is currently protected.

So why is this treaty so important? “First and foremost because it took us twenty years to achieve it,” comments Ms Bianco. “Secondly, because it lays the legal groundwork to establish marine protected areas (MPAs) on the high seas, which until now have been treated as no-man’s-land, stretches of sea where biodiversity is protected with a view to sustainable development.” This treaty is also key to achieving the goal of protecting at least 30% of the ocean by 2030, in terms of both land mass and marine ecosystems.

“Lastly, it is a true landmark treaty because it sends a message of hope in cooperation between states. As David Attenborough said in his memorable COP26 Climate Summit Glasgow speech, “If working apart, we are force powerful enough to destabilize our planet, surely, working together, we are powerful enough to save it.” Working together, powerful, and quick – towards the next word in the glossary, which will be time.

It will be possible to swim in the Seine again. This news unites sport, love of water and protection. In fact, 100 years after swimming in the river was banned, the mayor of Paris, Anna Hidalgo, has announced that she intends to make the river safe for swimming in time for the open water swimming and triathlon competitions at the 2024 Olympics. The goal is to clean up three-quarters of the pollution, improve wastewater treatment capacity to prevent sewage from pouring into the river, and open bathing establishments along the river: “If we reach this objective of reducing pollution by 75 percent, then it should be possible to swim in the Seine”, said the prefecture of Île-de-France.

time

n. [lat. tĕmpus -pŏris, a voice of uncertain origin]. The impression and representation of the manner in which individual events follow one another and are related to one another (whereby they occur before, after, or during other events); this fundamental impression is, however, conditioned by environmental factors (biological cycles, the succession of day and night, the cycle of the seasons, etc.) and psychological factors (the various states of consciousness and perception, memory) and differs historically from culture to culture

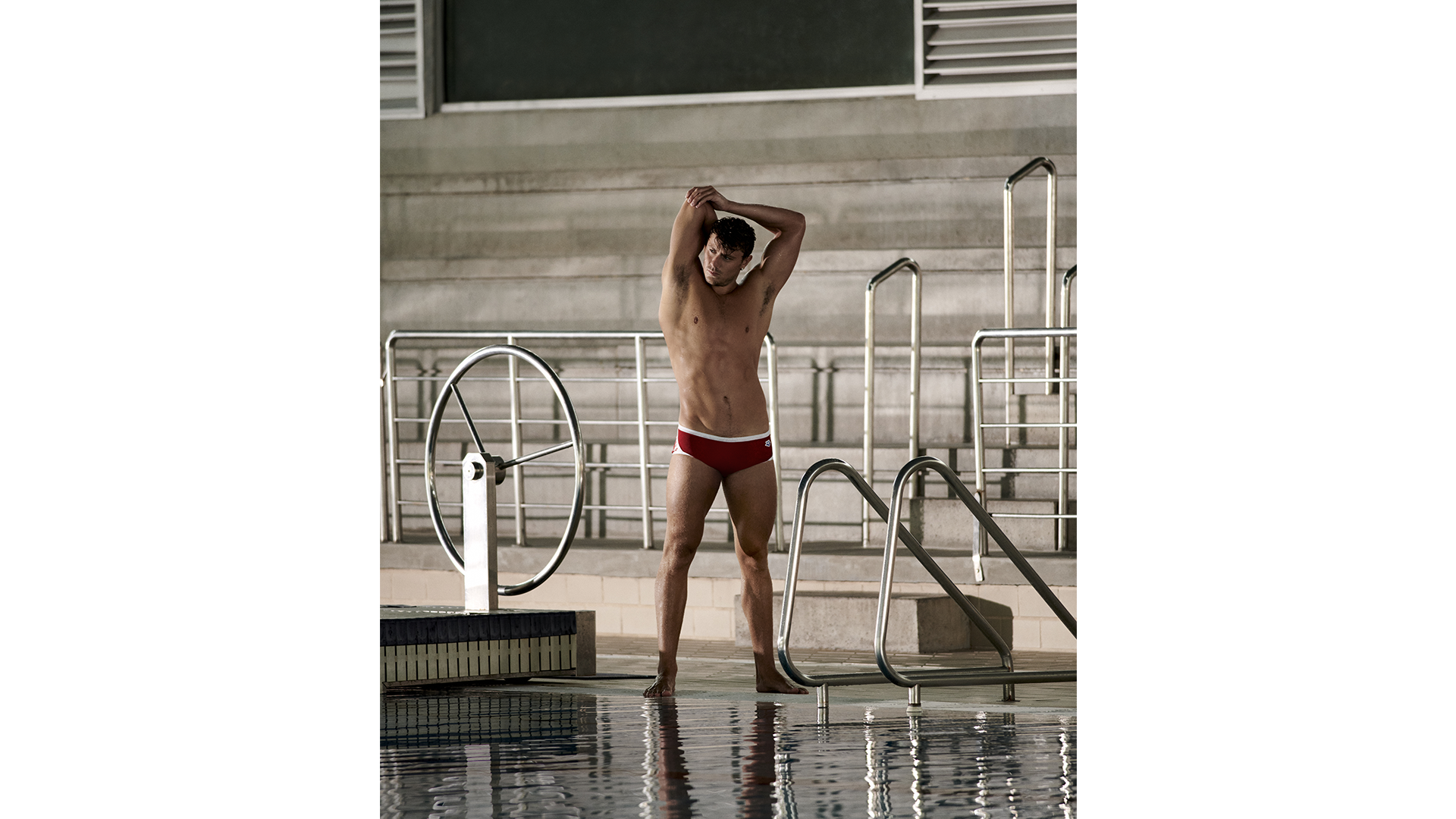

“I have probably spent more time in the water in my life than out. I consider it my natural habitat. It makes me feel alive!” On his Instagram profile, breaststroker Nicolò Martinenghi never misses an opportunity to share the deep passion that ties him to the water and to talk about his exceptional relationship with time.

The first Italian to break through the 59-second barrier in the long course 100m breaststroke, when he was still a young hopeful, Martinenghi, known as “Tete” achieved this at the 2020 Tokyo Olympics (held in 2021 due to the pandemic). His time of 58”33 won him the bronze and broke his own record. At least until the World Championships in Budapest 2022, where he won gold with a time of 58″26. In the 100m breaststroke – his speciality – he now holds both the World and European championship titles, which he will defend at the World Championships in July in Fukuoka, Japan.

“My time at the World Championships was pure joy,” he smiles over the phone. “Because I raced with my head as well as my body. Then I swam the same time at the Europeans, where I might have expected to improve it. But that is still my target time, the time I set myself to achieve and start from.” Tenacious, clear-sighted, mature. He no longer needs to play the envelope time: “Before a major event, my coach Marco Pedoja would write down the time he expected me to achieve and open it when the race was over. It was very stimulating for me, it pushed me to exceed my limits. Now that number is enough for us to think about. And then before the World Championships we had told each other that this wasn’t a race to set a time. It was a race to win.”

Swimming is the most meritocratic sport in the world – your time is the deciding factor; I race against the clock.

Nicolò Martinenghi

Man does not live by the stopwatch alone. Certainly not Martinenghi anymore. When he is training, while he’s swimming in the pool, the ticking of the hands is now white noise: who cares how long it takes? Only the strokes count, the breathing, the distance to cover, the detail to perfect. One last question, before our time runs out. The ancient Greeks used two words to define time: Chronos to indicate quantity, the passing of the minutes, and Kairos to refer to its qualitative nature, namely the ability to do the right thing at the right time. Which definition do you think best suits you? “The second one for sure. I don’t just quantify time with a stopwatch. I also live it every day outside the sport and the world of swimming. Doing the right thing at the right time is my philosophy.” Speaking of timing and common sense, if there is one thing that cannot wait any longer, it is the practical commitment of politicians, governments and institutions to tackle climate change. It might seem like a triple somersault to go from the record times of an Olympic champion to the environment, but it isn’t: of course, water plays a part.

Seven years to save the oceans

The latest warning comes from the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC). Protecting 30 per cent of the oceans by 2030 and net-zero carbon emissions by 2050 are just two of the most urgent goals to save the Earth from irreversible catastrophe. Yet, one hundred years feels like an eternity. For example, we find it hard to imagine how the sea can change in the next century any more than it has done in the last fifty million years, under the blows of ocean acidification, plastic pollution and the overexploitation of its resources. As Icelandic author and activist Andri Snaer Magnason insists in his book On Time and Water, “how can we act with the same urgency to protect the foundations of life for our loved ones in 2050, 2060 or 2080?”

One answer comes from the scientific community, which believes that at least 30 per cent of the oceans should be fully protected by 2030. The value of marine sanctuaries, i.e. areas completely free from human exploitation, is widely recognised as not only protecting key habitats and species, but also enabling their recovery and fostering their resilience.

30×30 A blueprint for Ocean Protection is a report that shows how it is possible to design a planet-wide network of high seas protected areas. The blueprint is the result of a collaboration between leading academics led by a team from the University of York in the UK, with the aim of providing a useful tool for institutions. In this respect, the agreement on the protection of the oceans, reached on 4 March, marks a historic turning point, rekindling hope.

Drought and a lack of snow in the mountains are two of the most obvious and visible phenomena of ongoing climate change. For the past few years, they have also had a direct impact on European countries and affect the supply of freshwater that we use for drinking, washing, growing fruit, vegetables and cereals, and producing energy. We now face the prospect of a 40% shortfall in freshwater supply by 2030, with severe shortages in some water-constrained regions of the planet. This is according to the report published by the Global Commission on the Economics of Water: “We need a much more proactive, and ambitious, common good approach. We have to put justice and equity at the centre of this, it’s not just a technological or finance problem.” explains Mariana Mazzucato, Italian economist and a lead author of the report.

current

n [countable – plural currents]. The steady and continuous movement of water in the same direction; ocean current; warm currents; swimming against the current ≈ flow. ‖ river, rapid.

It’s Sunday February 5th. On the Antarctic Peninsula, a day like any other is about to be a day to remember. Barbara Hernandez is standing, poised, on the edge of a dinghy. She looks up and through the fog catches a glimpse of the towering contours of the Chile Bay glaciers. Abruptly she dives in: the water is freezing cold and the 37-year-old Chilean is wearing only a swimming costume, swimming cap and some goggles. When the thermometer reads 2 degrees, every stroke is a mammoth undertaking, even if the international press and everyone back home (Chile) call you the Ice Mermaid: “I didn’t really feel cold at first, the hypothermia only kicked in towards the end. But I savoured every single moment of this swim. I feel at home in the water and this was my dream.”

In the end Hernandez swam two and a half kilometres in the company of a penguin. “It was incredible!”, her eyes sparkled. The longest distance ever swum in the Antarctic, without a wetsuit or protective grease and she dedicated her second Guinness world record to environmental protection: “The warm and salty currents that are melting the polar ice caps are one of the most serious effects of climate change and this is causing unimaginable imbalances on the entire planet. Seeing the Antarctic Peninsula without snow was a real shock to me. Although we don’t get many pictures from Antarctica, all our plastic, waste and CO2 are destroying this continent.”

The ACC plays an irreplaceable part in keeping the world’s ecosystems stable and in regulating the climate on earth. A 2021 study concluded that it is likely accelerating sea ice melt in the region, not good news by any means. Because if the Antarctic Circumpolar Current accelerates due to so-called “heat pockets”, the carbon dioxide absorbed by the oceans could rise from the depths to the surface. This way, the oceans, which absorb almost a third of the excess heat in the atmosphere, could end up being a source of carbon dioxide and the Southern Ocean’s capacity to absorb CO2 would be reduced.

I’ve learned to love the water not for the medals but for what it stands for.

Barbara Hernandez

The conversation about it is still too little, particularly where it counts. Which is why Hernandez is swimming her peaceful battle: “I think that with our commitment, mine, my team’s and that of everyone who loves nature, we can create a new current of thought. Public opinion is critical for defending the environment. There is so much we can do to show our connection with what is happening on our Planet. We have an obligation and a duty to try to preserve these beautiful landscapes. But we must join forces, without borders.”

Antarctica is melting faster than expected

The Amundsen sea, the fastest-growing region of Antarctica, four times the size of the United Kingdom, has lost more than 3 trillion tonnes of ice in the last 25 years. If all its glaciers were to melt, the global sea level could rise by more than a metre on average across the planet. Another important finding is linked to this: the Antarctic ice shelves could melt 20 to 40 per cent faster than expected. The culprit is apparently a small ocean current that is not usually taken into account in forecasting models, precisely because of its small size. David triumphs over Goliath because, unlike mountain glaciers, Antarctic glaciers melt from below. And if we do not do everything we can to preserve them, they will end up as nothing more than a memory.

memory

noun [from the Latin memor meaning “mindful” or “remembering”]. In general, the capacity, common to many living organisms, to store more or less complete and lasting traces of things learned and retained from their activity or experience and their responses (information relating to events, images, sensations, ideas).

The first time Florent Manaudou entered the pool, he literally hit rock bottom. The swimming teacher held onto a pole submerged in the water and the young pupils had to climb down it as deep as possible. “I was three years old and I didn’t know how to swim. So, it wasn’t easy. But then things got better,” he jokes.

Now the French swimmer is 32 years old, with many of those years spent winning medals in the world’s most prestigious competitions, including the Olympics. Something that runs in the family, given the career of his sister, former swimmer Laure Manaudou. It is natural to assume that his fondest water-related memory involves a place on the podium, like the gold medal in London in 2012. What a cliché. “The thing I would most like to remember has nothing to do with anything like that. What I really want to keep in my mind forever is how I feel every time I get into the water – the sense of peace, tranquillity and that indescribable silence.” Nothing could be truer or more universal: as the marine biologist Wallace J. Nichols – known for his studies on blue spaces and the human mind – argues, water shuts out the hubbub of land-based noises and this fosters a kind of meditative state in people.

“It’s impossible to forget that feeling of water against your skin. Do you have any idea what it’s like to move on dry land for someone like me, two metres tall and weighing a hundred kilos? In the water I feel light in every way, like a dolphin.” Maybe partly because he missed his aquatic weightlessness, he returned to competing in the pool in 2019, after a three-year break dedicated to handball. The next challenge will be qualifying for the world swimming championships in July. To be tackled with energy, acumen and respect. “Sometimes we forget how mysterious and unpredictable water is, calm and powerful at the same time. When I swim, it’s not just about being strong and pushing through the water, it takes intelligence. With water, you have to be kind.” A kindness that water reciprocates, as we will see in a moment, helping us to shake off troubled memories.

I would like to always remember how I feel when I get into the water – the sense of peace, tranquillity and that indescribable silence

Florent Manaudou

Water can help you overcome traumatic memories

If you suffer from anxiety or stress, also linked to past trauma, water can really help you. Although the publicity surrounding the restorative power of “blue spaces” – the sea, coastal areas, but also rivers, lakes, canals, waterfalls, even fountains – is less common than for green spaces, science has agreed for at least a decade that spending time in contact with water is good for your physical and mental wellbeing.

On the strength of this knowledge, the team from Rome-based not-for-profit association Sport Senza Frontiere (Sport Without Borders) set up the emergency action called “Sport di Prima Accoglienza” (Initial Reception Sport) aimed at supporting the minors and mothers who arrive in Italy from Ukraine via the humanitarian corridors, bringing with them traumatic memories of the conflict. “We believe that the element of water can be their “friend”,” the association explains, “a tool to help them cope with and prevent any post-traumatic disorders, a space where they can keep down the constant level of alertness in which both mothers and children live, an element that can boost motor skills and self-confidence, and that can foster the process of social inclusion for these people who have been living here for only a few months and who are still struggling to integrate socially, also because of the language barrier.”

Against this, the sound of the water in an empty seashell has no need of an interpreter. When you are facing the sea and the ocean, you feel joy and dizziness and an odd sensation of having been there before. Maybe because we spend the first few months of our lives in the water of our mother’s womb. Or maybe it’s because – millions of years ago – life left the ocean and moved to land only because every organism was able to take part of the ocean with it. “The cells forming every living organism continue to live under the original marine condition,” argued physiologist René Quinton in the 19th century. He claims that we are all a “living marine aquarium”. And it’s comforting to remember this.

oxygen

noun [from French (principe) oxygène, “acidifying constituent”, coined by French chemist Antoine-Laurent Lavoisier in 1779). The most common and abundant chemical element in nature, as molecular species, O2. The proportion of oxygen by volume in the atmosphere is 21 percent. It is found in the air, and in combined form, in water, in numerous minerals in the earth’s crust, in many inorganic compounds and in a large proportion of organic ones; a chemical that has no colour, taste, or smell, and that is necessary for breathing and, therefore, for life.

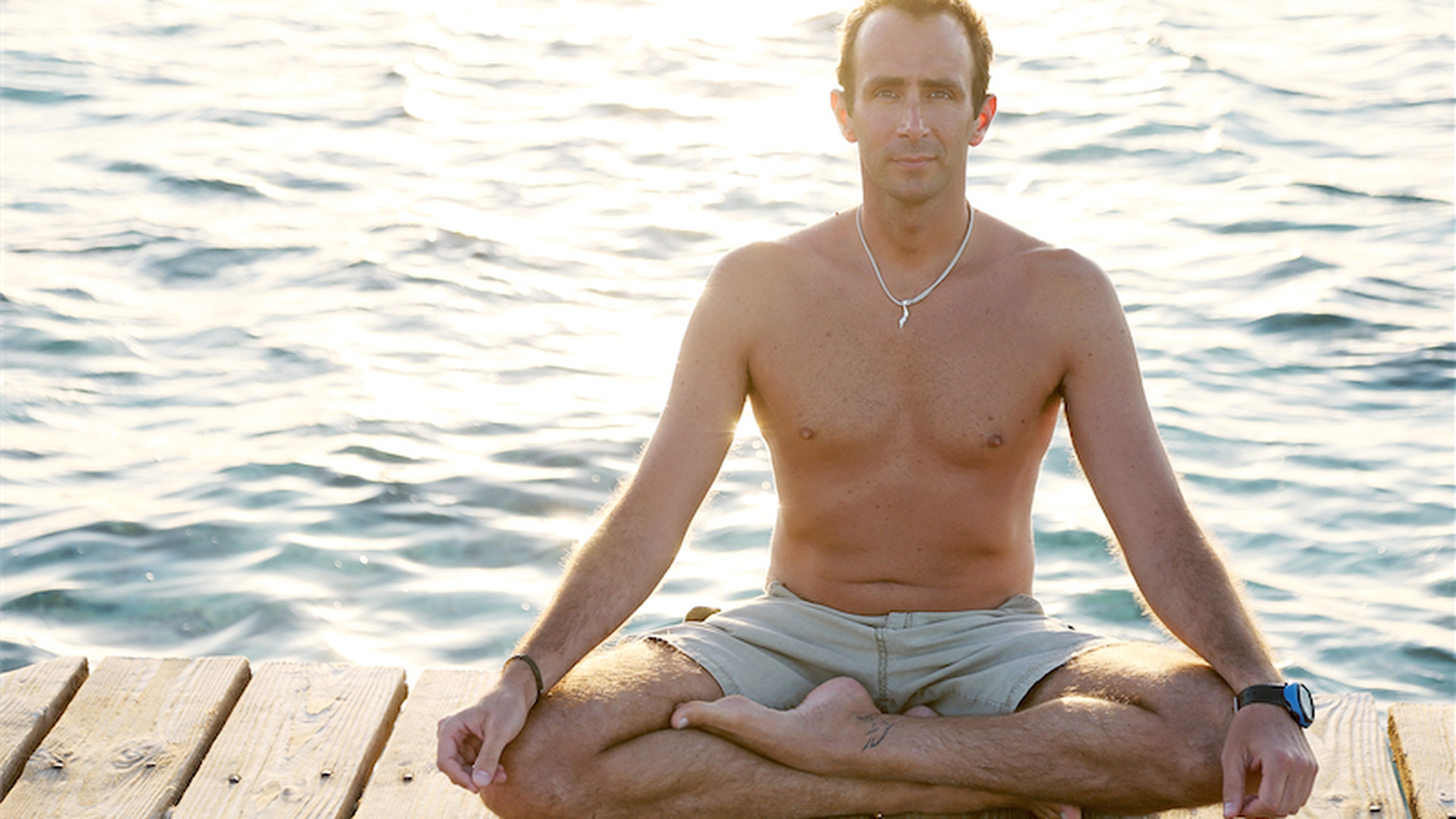

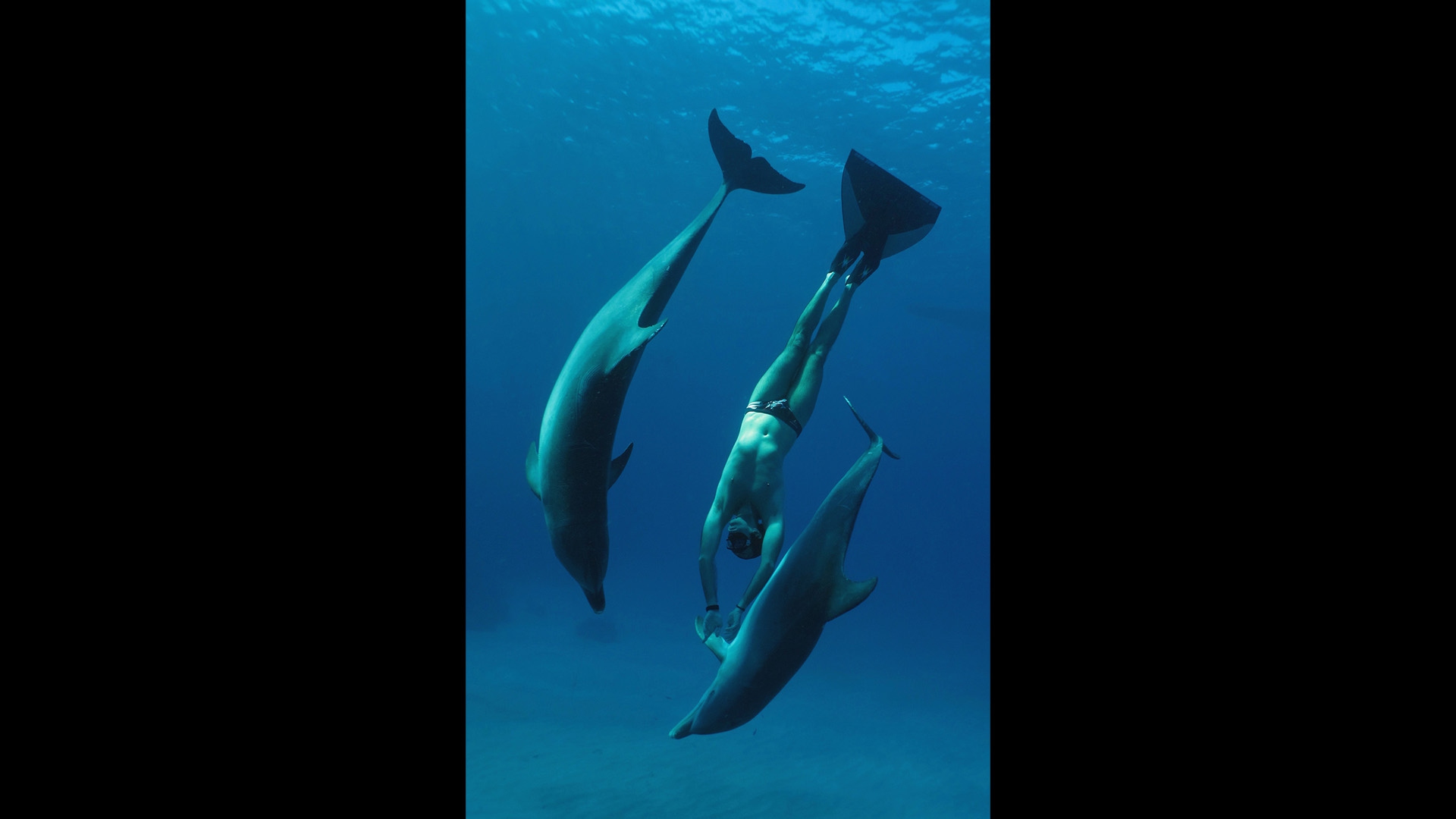

Darkness in the hall. A cone of greenish-blue light flashes on the screen and a creature from the abyss enchants us with its dance, set between two magnificent dolphins. That creature is Mike Maric, freediving world record-holder, doctor and coach to many Olympic medallists, whose life is celebrated in the docufilm Broken Breath. In short, just the person to talk to about water and oxygen.

“The word oxygen conjures up two concepts for me: the first is life, because oxygen is the element on which our very existence on earth depends. Without oxygen we could not exist. The second is water, meaning the sea, because 70 per cent of the oxygen we breathe comes from the oceans. Basically, we should be saying thank you to water every two breaths we take.”

His sensitivity to this topic stems from his past as a competitive freediver, someone who holds their breath when diving underwater as deep as they can, constantly challenging themselves to push beyond their limits. Today, eighteen years after the dramatic event that forever left its mark on his whole life and career (he lost a great friend at sea), Mike Maric teaches people to listen to themselves, to breathe properly in order to live better, providing training in apnoea and breathing for mental and physical wellbeing. The feeling of pleasure that comes from the conscious pause between an inhale and an exhale is very reminiscent of yoga techniques practised out of the water, “but this element gives us an extra edge,” Maric points out. “It sets us up for relaxation, it slows down our metabolism and heart rate. Water is much more of a friend to us than we think.”

A one-way friendship, judging by the dramatic data of recent decades. Because if the water in the oceans is the planet’s blue lung, we are stopping it from breathing. From the nineteenth century to the present day, the ocean has absorbed billions of tonnes of greenhouse gases produced by humans. Had it not been for the seas, since the 1970s the temperature on Earth would have risen by 36°C, instead of the actual 0.55°C. Who could have survived in such a world? Today, however, the vessel is full – the sea is much warmer than it used to be and consequently has less and less oxygen.

Every time I free dive, I experience a kind of moon landing. I lose my earthly dimension completely. I feel like water in water.

Mike Maric

Already in the first week of April we sadly beat a record. Data from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration – the US agency responsible for ocean and atmospheric studies – showed the average temperature at the ocean’s surface has been at a record high of 21.1C – beating the previous high of 21C set in 2016. And the millions of fish that suddenly died in an Australian river as a result of an abnormal heat wave, which reduced oxygen levels, are yet another casualty in the devastation wreaking havoc on marine life worldwide.

Sadly, though, while heat is the main cause of ocean deoxygenation, it is not the only one. After all, we have known for a number of decades that discharging synthetic chemical fertilisers from farming into the sea triggers an overgrowth of algae, which are large consumers of oxygen, to the detriment of other species. “The oceans are losing their breath. Fish are now becoming shadows of plastic and this pains me greatly,” Maric concludes. “Nature will soon be only in black and white and we will be leaving the future generations a very poor legacy. My call is to not lead the selfish life of today and to embrace altruism. We know what needs to be done. So, let’s get it done.”

Warmer, depleted oceans mean more frequent hurricanes, including in the Mediterranean (Mediterranean tropical-like cyclones are often referred to as medicanes) and food shortages. Drastically reducing greenhouse gas emissions now and addressing what is already in motion are the only viable choices for our survival.

wave power

also called ocean wave energy. Electrical energy generated by harnessing the up-and-down motion of ocean waves. It is categorised as what is known as alternative and renewable energy, and is considered the most constant because, unlike the sun and wind, the sea is in continuous motion.

There are waves that produce the energy needed to turn on electric switches. And others that can instead make you smile. The difference lies in how we interpret the expression wave power. What does this mean? In technical terms – as it says in the box above – it means converting the incessant movement of the sea into electricity. But if you put the same question to a surfer, or to an Olympic freestyle gold medallist and open water bronze medallist like Gregorio Paltrinieri, another world will open up to you.

“When I swim in the sea, I feel like I’m in a completely different dimension than on earth. I feel like I’m in space. Allowing yourself to be gently rocked by the waves is an indescribable feeling,” says Greg. Rediscovered lightness after a “short circuit of the soul” experienced in the months leading up to the gold medal victory at Rio de Janeiro in 2016. “At the time, before Rio, I was winning everything. And everyone started to take it for granted that I had gold in the bag. I felt like I was carrying a weight, the weight of water. After that experience, my journey lightened up a bit – I gained a lot of experience and my approach to competition improved, also thanks to the sea. In open water, you have to be creative, ready to make on-the-spot decisions and face the unpredictable.”

After his successes at the European and World Championships, the champion set his sights on the Paris Olympics and devised a new challenge linked to open-water swimming, at the same time raising awareness about protecting Italy’s seas and beaches. “A friend and I came up with the “Dominate the Water” project in 2021. This race is open to anyone and everyone – our aim is to convey passion and respect for the water through sport. That’s why we collaborate with associations dedicated to safeguarding these ecosystems. It’s important to know the impact of our daily actions on the environment – it makes you a participant and responsible for what happens.”

When I swim in the sea, I feel like I’m in a completely different dimension than on earth. Allowing yourself to be gently rocked by the waves is an indescribable feeling.

Gregorio Paltrinieri

Sea, waves, surf. Do you like surfing? “It’s probably my favourite sport!”, confesses Paltrinieri. “It makes me feel so free – it’s rare to experience quite the same rush of adrenaline as when you catch a wave and stand up on the board. Every single time, it leaves me slack jawed with excitement.” A mix of joy and wonder that everyone can experience.

The surfing army fights for inclusion and mental and physical health

If you get around in a wheelchair or suffer from depression, being physically active is paramount and yet it can often prove to be a mammoth undertaking. Let alone if it involves braving the churning waters of the Atlantic Ocean. That’s why Tom Butler founded Coastal Crusaders, a Community Interest Company based in Cornwall, UK which offers young people with disabilities or mental health issues motivational, supervised opportunities to participate in a range of ocean activities, including group surfing lessons. This school is just one of the many organisations operating around the world in what is known as surf therapy.

While increasing evidence demonstrates the effectiveness of surf therapy, and the benefits of this sport discovered so far are common to many outdoor sports, especially water sports, there has been limited exploration as to how it achieves its outcomes. Compared to other sports, riding waves seems to deliver an invaluable extra dose of fun, self-esteem and a sense of belonging, as we can read in the numerous studies listed on the website of the International Surf Therapy Organization. In particular, a University of Edinburgh report highlights two aspects – attempting to catch increasingly difficult waves helps reduce the perception of failure and encourages peer support. One wave after another, like Forrest Gump’s chocolates, you never know what you’re going to get. The thing that really counts is working together to build the confidence to get back up, carried along by the power of the waves.

confine

noun – [from Latin confine, neuter of confinis “bordering on”, from assimilated form of com “with, together” (see con- + finis “an end”]. A line separating one country or state from another; something, often natural that shows where one area ends and another area begins (such as a coastline, a mountain ridge, or a river).

In all her photos, her radiant smile, long blond hair and medal next to her face portray Jessica Long as the quintessential successful swimmer. Over her career, which began when she was only ten years old, she has won 29 paralympic medals (sixteen gold), and is the second most successful athlete ever in a single sport. Much more than others, Jessica Long knows what it’s like to win by overcoming inner boundaries and those instilled by society in people who, like her, have no legs from the knee down or were born with other forms of disability. “Before I dive into the pool, people see me as a girl with a disability, they think about medals, labels. In short, they have their own ideas about me. But when I enter the water, I break every barrier and remind people that you can do crazy things, even without legs,” says Jessica.

From an orphanage in Siberia to the backyard pool of her adoptive parents in Maryland, to world championship podiums and the commercial about her life screened during the Super Bowl, the redemption of the woman often referred to as “Aquawoman” also serves to mark the fine line between the improbable and the possible. As long as you have the courage to step over it, and face the obstacles. “For a long time, as a swimmer, I identified with my wins. Identity is a difficult barrier to overcome in all fields, not just in sport. I struggled to realise that I love swimming but that what I do does not define who I am. I want to be recognised as an inspiration, a good teammate, not just for my gold medals.”

I feel light only when I’m in the water. Swimming gives me the freedom to feel empowered in my body.

Jessica Long

From a story of water that loosens our innermost knots, it’s not all that complicated to switch registers. Because this precious resource can become a useful picklock to reach another kind of peace, especially when it flows beneath the land of two or more neighbouring countries.

Border waters are a key to peace

On 27 August 2019, Armenian photojournalist Anush Babajanyan was confronted with an almost miraculous scene: a hot spring emerged from the dried-up bed of the Aral Sea on the border between Uzbekistan and Kazakhstan. An unexpected treat for the women immortalised in the shot, which is now making the rounds of the world along with the other magnificent shots from “Battered waters”, the 2023 winner of the Long-Term Project Award in the world’s most famous photography competition – the World Press Photo.

Tajikistan, Kyrgyzstan, Uzbekistan and Kazakhstan: Anush Babajanyan’s work documents four Central Asian countries struggling with the climate crisis and lack of coordination over the water supplies they share. Cross-border water management is a common problem, when 40 per cent of the world’s population live near river and lake basins shared by at least two countries. And this percentage rises if we add the sharing of underground aquifers.

Geopolitical experts see this as a veritable time bomb of possible water wars, especially right now, when food and water insecurity is increasing worldwide. According to the Global Early Warning Tool developed by the Water, Peace and Security (WPS) partnership, millions of people could soon experience violent conflicts over the supply of resources, water first and foremost. Which is also why the United Nations developed an important practical guide. Because despite everything, transboundary water resources “provide opportunities for cooperation and promotion of regional peace and security as well as economic growth.”

One virtuous example of water resource management is the case of the Senegal River. This majestic waterway represents a 1,800-kilometre lifeline for farm production in a mostly desert, densely populated region. Complicating matters even further is the fact that the river flows through three different countries – Mali, Mauritania and Senegal – and its tributaries flow along a fourth country, Guinea. Yet, the diplomatic approach of optimal distribution among users has ensured peaceful management. The Senegal River has a long history of water cooperation among the basin states (dating back to colonial times) and some 13 international agreements have been signed. In 1972, the Organisation for the Development of the Senegal River (OMVS) was created and has been monitoring the course of the river, regulating power grids and industrial development. And Mauritania, Mali and Senegal share ownership of the dams.

Hydro-inclusiveness

neologism. Hydro [from Ancient Greek ὑδρο- (hudro-), from ὕδωρ (húdōr, “water”)]. – Word-forming element in compounds of numerous learned words and scientific terms, derived from Greek (hydrophobic, hydrophilic), or formed later (hydroplane, hydrotherapy), in which it means “water”. Inclusiveness noun. The capacity to include as many people as possible in the enjoyment of rights, activities, processes and actions; more generally, the inclination, tendency to be welcoming and non-discriminatory, deliberately including people who might otherwise be excluded or marginalised as a result of judgement, prejudice, racism and stereotyping, such as those having physical or intellectual disabilities or belonging to other minority groups.

“I realised early on that there weren’t many people who looked like me in this sport. I was five years old and one day I was playing with a white kid after swimming class – he told me he hated me because I was black. I remember it like it was yesterday.” Simone Manuel is now 26 years old and a freestyle champion; she made history as the first African American woman to win gold in an individual swimming event (Rio 2016). But it’s outside the pool where she has achieved some of her most courageous victories, by raising her voice and taking action on such taboo subjects as systemic racism in the world of swimming.

Apart from the competitiveness, the numbers are impressive. About 64 per cent of African American children don’t know how to swim, against 47 per cent of their white counterparts. And according to the Swim England, the sport’s governing body in the UK, 95 per cent of black adults and 80 per cent of black children in England do not swim, and only 2 per cent of regular swimmers are black. This is an alarming statistic with life-threatening implications, because staying afloat isn’t the same as riding a bike or playing tennis. It is an essential skill to prevent the danger of drowning and being a member of an ethnic minority is one of the factors associated with an increased risk of drowning, also according to the World Health Association.

In the poignant You Tube documentary “Head above water” – well worth 15 minutes of our time – the American swimming star speaks up on another issue that is still too often silenced, the mental health of athletes. Before the Tokyo 2021 Olympics, Simone was diagnosed with overtraining syndrome, which occurs when an athlete isn’t given adequate recovery after repetitive intense training. She experienced depression, anxiety, and sleeplessness. And when she talked about this in a press conference, things didn’t go the way she hoped they would. “People said that I was distracted by all my other sponsor obligations, and that’s why I didn’t perform well. That I became lazy and my success went to my head. It’s really hard to be vulnerable in that space.”

When I felt like quitting. I thought about Cullen Jones, Tanica Jamison, Sabir Muhammad, and Maritza Correia McClendon. Their stories taught me that my dream should never be limited by the assumptions of others.

Simone Manuel

Now that she is back on track, Simone says she is ready to take her “black girl magic” to the Paris 2024 Olympics. Where more good news is in store, to do with water and inclusiveness.

Swimming is also a question of gender

On 22 December, World Aquatics (formerly FINA, the international swimming committee) and the International Olympic Committee took a huge step towards inclusiveness. For the first time in Olympic history, at Paris 2024, men have been given the go-ahead to participate in the artistic swimming competition.

And the comments weren’t long in coming. The athletes in particular had plenty to say, heralding the decision as a milestone in the history of swimming and sport in general. Why? The USA’s Billy May, the first male World Champion in artistic swimming and revered star of the discipline said it well. “The inclusion of men in Olympic Artistic Swimming was once considered the impossible dream.” The fact is that while artistic swimming has been on the Olympic programme since 1984, until now – at Paris 2024 – it has always been a female-only sport.

Historically, men haven’t been considered the ideal fit for this sport, because they are many times physically heavier and often less flexible, so it is harder for them to float. Yet some male artistic swimmers have begun to break the stereotypes that surround them, while also conveying the beauty of masculine elements in the sport. As Giorgio Minisini, spearhead of the Italian team, explained to CNN. “Being a man doesn’t mean that you have to be a certain kind of man. Being a woman doesn’t mean that you should be a certain kind of woman. You can be whatever you want.” It’s also thanks to athletes like him that we’re seeing change at Paris 2024. Ten teams and 96 athletes – who will “sink or swim” (like in the French film, Le Grand Bain) – will be competing for gold in the artistic swimming competition at the Olympic Aquatics Centre.

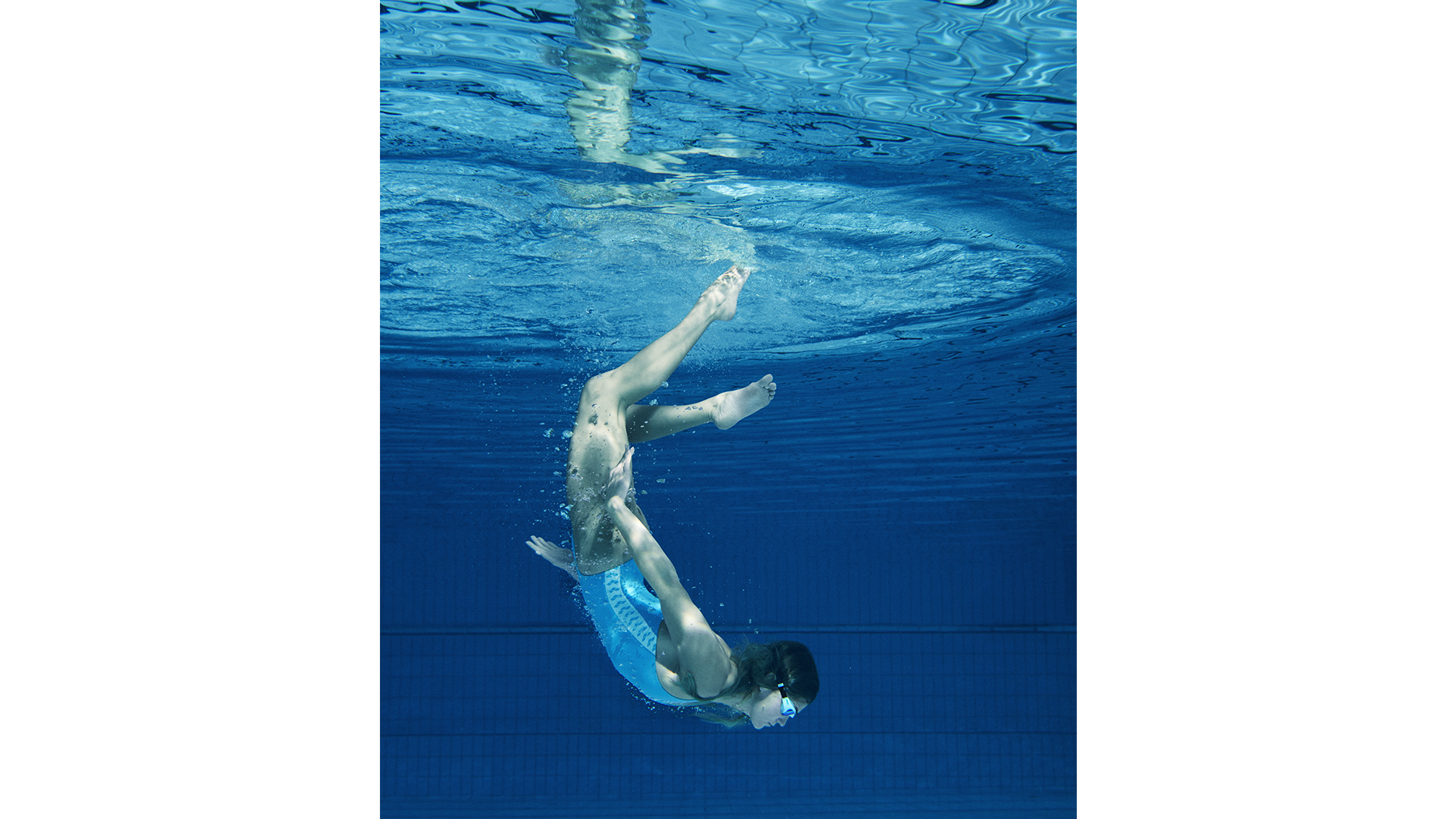

dives

singular dive – noun [from a merger of Old English dufan “to dive, duck, sink” and dyfan “to dip, submerge”] – To descend or plunge headfirst into water: a plunge in the bath; a jump into water with your arms and head going in first; an act of swimming underwater usually while using special equipment (such as a snorkel or air tank); a usually steep downward movement – a submarine submerging; underwater sports testing both endurance and depth.

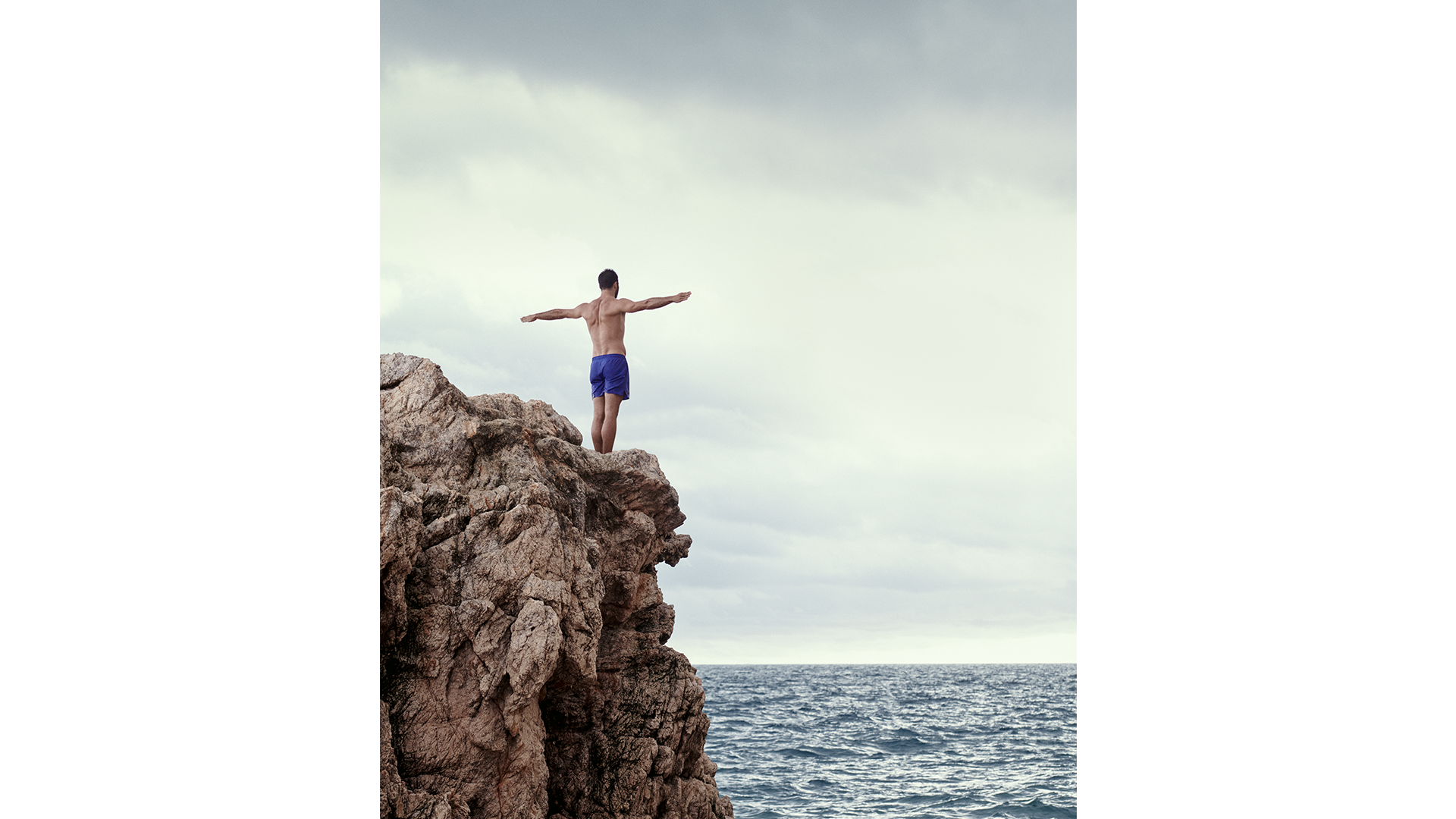

Ellie Smart thought she was done with diving. Born in 1995, a lifetime spent training in Kansas (her homeland) and California, the Olympic Games as the focus of her umpteenth dive. Then the disappointment. “I didn’t qualify for the Rio 2016 Games, so I gave up,” she says. But that’s where the fun really begins.

In her early twenties she took part in a high diving competition almost as a joke. Twenty metres above the sea, somersaults in the air and a final dive into the blue: just watching the cliff divers on YouTube gives you the shivers. “It was like I unlocked a whole new level of myself. I could have continued diving, or I could have become a doctor, a lawyer, or anything else, but that dive unleashed an incredible potential that I honestly didn’t realise I had.” Sunken treasure, pirate of the soul.

The word “dive” makes me think of the expression “to attempt the impossible”. Anyone can jump off a diving board – facing your fears is the most rewarding thing in the world.

Ellie Smart

Nowadays, from Polignano to Beirut, from the Philippines to Greece, Ellie travels the world as a professional cliff diver, and at the same time, she is involved in cleaning beaches with her Clean Cliffs project: “Unfortunately, plastic pollution is a common problem in these beautiful places. I wanted to leave a positive impact, so I started to organise some beach clean-ups,” Smart explains. 2023 will be the year of the big leap, with a global tour and a series of events open to all. What will you be doing on 8 June, for World Oceans Day? “I’m hoping to organise a mega beach clean-up, of course.”

The Oceans, first and foremost

On Planet Ocean, the tides are changing, and that’s good news. The theme chosen by the United Nations for World Oceans Day 2023 on 8 June describes an unstoppable and, hopefully, irreversible phenomenon: tides are changing, as we can see from the increasing number of people fighting to finally put the protection of the sea first.

Testament to this is the High Seas Treaty, that lays the groundwork to ensure the protection and sustainable use of marine ecosystems, to put an end to the disastrous actions perpetrated in this lawless ocean, and well documented, for example, by the investigative journalists from The outlaw ocean project. This is confirmed by grassroots initiatives like those of Ellie Smart and biologist Mariasole Bianco, who we met at the beginning of this dive into the words that tell the story of water. The goal is to protect 30 per cent of the oceans by 2030. That’s just around the corner, and scientists from the International panel for ocean sustainability, who came to Brussels from all over the world in April to stress the need for a strong link between science and policy to provide scientific data for the sustainable management of the oceans.

8 June 2023 is a very important date: the official UN conference in New York, which you can watch live, will be where the seeds of the near future are sown.

Dives is the term that concludes this glossary. But diving into what? Here, right where we are right at this moment in time. Clouds, rivers, rain, lakes, water vapour and ice crystals: from earth to sky, we live in a “shell” of water, the hydrosphere. We owe half of the oxygen we breathe and 70 per cent of what we are to water. Our fate is bound up with that of the sea. Granted, a storm is brewing. But the last word hasn’t been said yet.