A special report from the Yuqui territory delves deep into the dreams, challenges, joys and sadness of one of Bolivia’s most vulnerable indigenous groups.

Indigenous Maasai people have been ordered to leave their homeland in Tanzania’s Serengeti Park for it to be turned into a hunting ground for tourists, a report highlights.

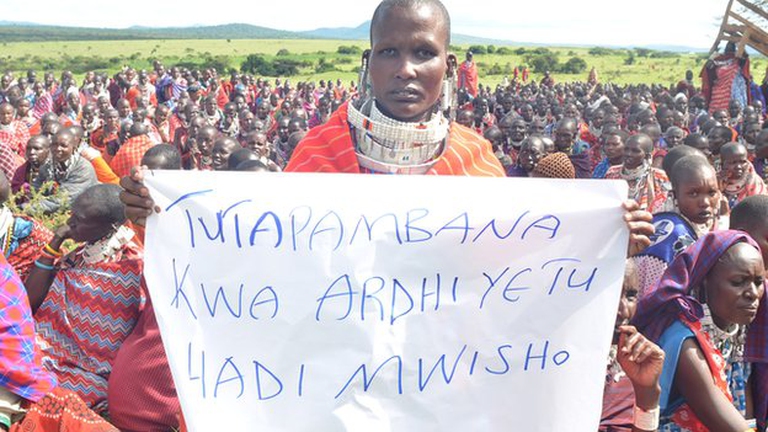

Maasai people from four villages in Loliondo, on the outskirts of the Serengeti National Park in Tanzania, famous for the annual wildebeest migration, are being evicted from territories they’ve occupied for thousands of years, according to an investigation by think tank the Oakland Institute, in a case of land grabbing. The Maasai represent one of the largest known pastoral groups worldwide, with about one million people roaming across southern Kenya and northern Tanzania, but “hundreds of homes have been burned and tens of thousands of people driven from ancestral lands in recent years to benefit high-end tourists,” the report highlights.

Tensions between the Maasai and the Tanzanian regime began in 1992, when the latter licensed Otterlo Business Corporation, owned by a senior official of the United Arab Emirates government, to organise hunting expeditions in Loliondo, a 4,000 square kilometre stretch of land on the edge of the Serengeti Park in northern Tanzania, near the border with Kenya.

For almost two decades the indigenous herding communities and foreign trophy hunters managed to coexist. Until 2009, when the Tanzanian regime imposed stiff laws that completely prohibited the indigenous people from farming and herding cattle within a 1,500 square kilometre stretch of the Lolondio Game Controlled Area, where licensed hunting is allowed.

On the back of these laws, armed agents swooped into the area, arresting and torturing its inhabitants and demolishing hundreds of homesteads.

Read more: LifeGate’s Manifesto on how to organise responsible travel

Not surprisingly, environmental and conservationist activist have cried foul. Despite tourism being a major revenue contributor towards Tanzania’s national budget, critics say the government has prioritised safari firms at the expense of indigenous communities.

“What is appalling to us is that the government has been reviewing boundaries and subsequently evicting communities in the name of conservation,” Hellen Kijo-Bisimba, head of the Tanzanian Legal and Human Rights Centre, denounces. “This really makes me weep because the pastoral lifestyle of these indigenous people will become a thing of the past,” she said.

She continued, pointing out that it’s shocking that the Tanzanian government can choose to sign what she describes as a death warrant for thousands of animals, in exchange for money. “The only reason there are still big cats and large game animals in the Serengeti National Park is because the Maasai are involved in the conservation process,” she concluded.

Since Otterlo was first granted 400,000 hectares of land for hunting, the government has mounted successive eviction operations. “The company has warned the area needs greater ecological protection because herds are increasing while water sources are drying up due to climate change,” says Auradha Mittal, executive director of the Oakland Institute. He also wonders why the Tanzanian government has chosen to side with a safari company who is encroaching on the customary land rights of the Maasai community.

Moreover, in defiance of past governments’ promises that the Maasai would never be evicted from their land, the report notes Serengeti Park rangers burned 114 bomas (traditional homes) in 2015 and another 185 in August last year. Along with other demolitions, local media report more than 20,000 Maasai have been left homeless.

Read more: Sustainable tourism, a practical guide

Tanzania’s Tourism Minister Hamisi Kigwangalla said he was aware that a hearing had begun in court in which the Maasai people have sued the Tanzanian government. “There are no human rights violations and the government has found a solution to the conflict in Loliondo that is acceptable to all sides, these NGOs are just cooking up stories,” he maintained.

Meanwhile, Tom Kuirrung, a victim of the ongoing evictions in Serengeti Park complained of police brutality, adding that he and his fellow cattle herders are so afraid of authorities that, “we flee when we see vehicles approaching because we think they’re hunters who have connived with the state to arrest and beat us,” in his own words. He described Kigwangalla’s assertions as baseless and ridiculous.

One Maasai quoted in the report said Thomson Safari, another hunting firm operating in the area, “has built a camp in the middle the village, blocking access to waterholes and fertile soils. Imagine this, a stranger comes and constructs a big building in the centre of your home; how can you feel,” reads their testimony.

“It’s frustrating because our livestock can’t go to the waterholes because we’re constantly beaten, arrested and sometimes threatened or tied-up and driven off by uniformed armed officers. Our cattle are dying and sadly there are no other alternatives routes for us to access streams or fertile land to cultivate,” the Maasai details.

The restricted access to land has made the indigenous people more vulnerable to severe famine during drought years, and all the appeals locals have made for the government to change policy, in response to a growing number of children becoming malnourished, haven’t been fruitful.

Read more: How agriculture and climate change are related: causes and effects

Responding to the findings through a press query, Thomson Safari rejected the accusations levied against it, saying: “Our company employs 100 per cent Maasai staff, allows cattle on the property to access seasonal water and we’re also working with local communities and the government to conserve the savannah in terms of improving access to water and formulating a sustainable grazing policy,” the company stated in an email.

It was also quick to shift the blame for this and past conflicts in the Serengeti on NGO activists. “These activists stirred up villagers and led to staff being assaulted by young warriors armed with clubs, spears, knives and poison arrows,” it complained.

The Maasai people who sued the Tanzanian government for the right to return to their villages, now occupied due to hunting activities, have asked a regional court to stop the government intimidating witnesses supporting their legal bid to move back to their ancestral land.

“What is shocking at this moment is that the government is trying to intimidate the villagers to withdraw the case. The police have gone back to the community, they’re summoning leaders and arresting them. So far about seven men have been charged with attending an unlawful meeting,” Donald Deya, CEO of the Pan African Lawyers Union, who is representing the Maasai community in court, said.

Siamo anche su WhatsApp. Segui il canale ufficiale LifeGate per restare aggiornata, aggiornato sulle ultime notizie e sulle nostre attività.

![]()

Quest'opera è distribuita con Licenza Creative Commons Attribuzione - Non commerciale - Non opere derivate 4.0 Internazionale.

A special report from the Yuqui territory delves deep into the dreams, challenges, joys and sadness of one of Bolivia’s most vulnerable indigenous groups.

The Yuqui people of the Bolivian Amazon fight not only to survive in the face of settlers, logging and Covid-19, but to preserve their culture and identity.

Jair Bolsonaro is accused of crimes against humanity for persecuting indigenous Brazilians and destroying the Amazon. We speak to William Bourdon and Charly Salkazanov, the lawyers bringing the case before the ICC.

Activists hail the decision not to hold the 2023 World Anthropology Congress at a controversial Indian school for tribal children as originally planned.

Autumn Peltier is a water defender who began her fight for indigenous Canadians’ right to clean drinking water when she was only eight years old.

The pandemic threatens some of the world’s most endangered indigenous peoples, such as the Great Andamanese of the Andaman and Nicobar Islands in India.

The Upopoy National Ainu Museum has finally opened. With it the indigenous people of Hokkaido are gaining recognition but not access to fundamental rights.

A video shows the violent arrest of indigenous Chief Allan Adam, who was beaten by two Royal Canadian Mounted Police (RCMP) officers.