South African court dismisses a major lawsuit by 140,000 Zambian women and children against Anglo American for Kabwe lead poisoning. A setback for affected communities enduring the lasting impact of lead contamination.

Watch the video reportage produced by LifeGate A journey through Fukushima to meet farmers, food producers and restauranteurs five years after the earthquake, tsunami and nuclear disaster that shook Japan in March of 2011. Instead of desperation and abandonment, what characterises the prefecture is a community of motivated, resourceful and committed people ready to get back on their feet.

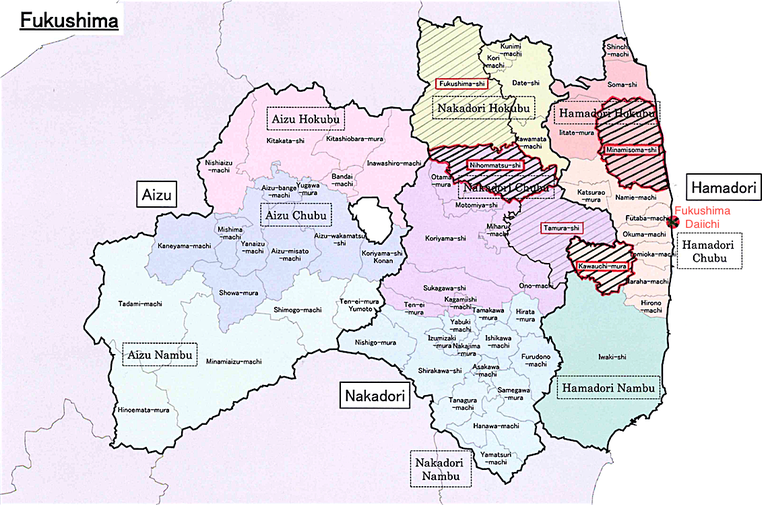

A journey through Fukushima to meet farmers, food producers and restauranteurs five years after the earthquake, tsunami and nuclear disaster that shook Japan in March of 2011. Instead of desperation and abandonment, what characterises the prefecture is a community of motivated, resourceful and committed people ready to get back on their feet. Whilst the rest of the world can’t let go of images of explosions at the Fukushima Daiichi nuclear power plant and fear of the spread of airborne and seaborne radioactivity, many residents are much more focused on the future than they are on the past.

However, they’re also worried about the marketability of their products – independently of the extent to which safety risks are real or perceived. The presence of radioactive caesium-137 and -134 and iodine-131 in soil and water raises serious health concerns, including increased risk of cancer. On the other hand, locals offer a reassuring message: inspections are systematic and radiation levels don’t surpass Japan’s legal limits. General foodstuffs (excluding specific products such as baby milk) can’t contain more than 100 becquerels of caesium-137 per kilo, compared to a limit of 600 in the European Union and 1,200 in the United States.

Behind discussions on the preventable nature of the disaster, the morbid relationship between energy regulators and TEPCO (the utility company that operates Fukushima Daiichi), and disdain for Japan’s intentions to continue pursuing nuclear development, are real people. Brave and intelligent individuals who, beyond our view, are working hard not just to survive a tragedy, but to build something new out of its ashes. Here are just a few of them.

Fukushima is home to over 150 hot springs, onsen in Japanese. Whilst tourism isn’t the economic lifeline it was before the earthquake, the prefecture receives visitors such as researchers inspecting radiation levels in towns like Nihonmatsu. We’re 50 kilometres from Fukushima Daiichi and just outside the evacuation zone that corresponds to the path of northwestern winds carrying radiation from the plant. Here one can take advantage of the warm and down-to-earth hospitality offered by local farmers such as Tatsuhiro and Miwako Ono.

The Onos used to grow mushrooms but are no longer able to due to contamination. They show images of the sizeable harvest they had to throw away in March 2011: the towering plastic bags are eerily reminiscent of the large sacks of contaminated soil that lie in clusters all over Fukushima (around 10 million in total). These are the result of the government’s decontamination efforts, aimed at reducing outdoor radiation levels to one millisievert a year (under normal conditions we’re exposed to double that on average) through the removal of topsoil. What will happen to the collected earth is yet to be decided.

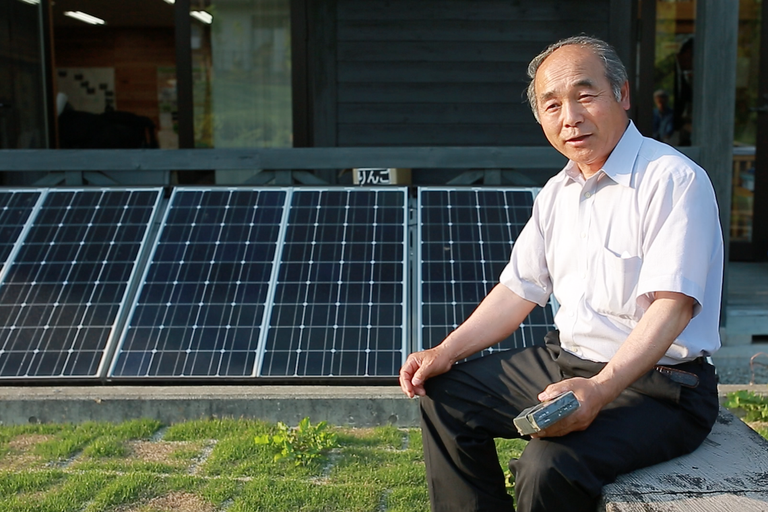

Since 2011, a lot has changed. The Onos cultivate tomatoes in a greenhouse above their home and rice in a number of paddies below it. The rice fields are lined with zeolite, a mineral that detoxifies from heavy metals, and adding potassium chloride so that the plants absorb it instead of caesium. All products are grown organically, as are those of adjacent plots thanks to an agreement between local farmers. Solar panels top the roof – the Onos highlight their desire for energy independence, understandable for Fukushima residents whose livelihoods have been shattered by the fallout of nuclear radiation from the power plant.

The NGO supports the Onos and other Nihonmatsu farmers in developing organic agriculture and homestay businesses, embodying the spirit of community action that ties many Fukushima residents. Whilst the government is legally bound to implementing decontamination efforts where radiation levels exceed 20 millisievert per year, communities are left to fend for themselves if they don’t (with the possibility of making a claim to TEPCO). Contamination has affected the lifestyles and livelihoods of all the prefecture’s inhabitants, but not everyone has the same access to government assistance, which will be discontinued next year. An invisible, arbitrary line divides who can make certain claims, such as those living in the official evacuation zones, and who can’t.

Yuukino Sato Towa has organised its own monitoring and clean-up efforts in the Nihonmatsu area with financial support from TEPCO. Since May 2011 it has coordinated an effort to monitor the radiation levels of many local products for a total of 9,000 inspected goods. Its main purpose remains promoting organic agriculture explains Secretary General Masatoshi Muto. It’s a way of encouraging sustainable and “clean” practices whilst increasing the value of Nihonmatsu-branded products, which can be bought locally and online.

Purple LED lights mask the florid green of stacks of leaf vegetables such as lettuce and Italian basil. This is KiMiDori Inc., Japan’s largest commercial hydroponic cultivation facility, a technique that uses mineral nutrients dissolved in water. It was opened in Kawauchi village – population around 2,500 before the earthquake, now 1,700 – in 2013 to give jobs to the residents returning after the evacuation order was lifted the following year. The community founded the enterprise with the government’s support, choosing hydroponic farming because it obviates the problem of using potentially contaminated soil.

KiMiDori counts 25 employees, some of whom are ex-Fukushima Daiichi workers. President Masakazu Hayakawa and engineer Maya Kaneko came from the capital Tokyo, around 250 kilometres away, to work here. 8,000 packs of lettuce and around 220 kilos of leaf vegetables are produced daily, sold in restaurants and local supermarkets. With an outstanding order of 100 kilos from a Tokyo chain, the plant is ready to expand and take on more staff.

Minamisōma is a coastal city only 20 kilometres from Fukushima Daiichi, where the Tōhoku earthquake and tsunami, as it is known in Japan, killed 469 people. It became a symbol of the destruction caused by the disaster after its mayor Katsunobu Sakurai posted a Youtube video asking the world for help, which resonated so profoundly that Time elected him one of the 100 most influential people of 2011. The city, once home to 71,000 people, currently has a population of 57,000. It is also the site of a research project conducted in collaboration with Fukushima and Niigata Universities in which over a dozen rice fields are being cultivated under different conditions to understand how to best mitigate the crop’s absorption of radioactive caesium. This is part of the Minamisōma farmland revitalization initiative.

Its president, Kiyoshige Sugiuchi, also heads the Canola Flower Project, located on the border of the evacuation zone. What was once a rice paddy lay barren after the earthquake. Now, these 35 hectares are cultivated with canola that is then made into an oil branded Yuna-chan, also used to produce mayonnaise. Sugiuchi explains that whilst caesium is absorbed by the plant, it isn’t found in the final product because the element doesn’t dissolve in oil. In addition, the company makes Tsunagaro Omoi soap in collaboration with the Japanese branch of cosmetics brand Lush. To Sugiuchi growing canola means planting the seeds of Fukushima’s future. It means making its products marketable again and offering work to its young — who have, as of yet, been weary of moving away from the lives and jobs they’ve become tied to in the last five years, and back to an area where businesses face extraordinary obstacles.

A plate of inaka-soba, “countryside” noodles made from locally-grown buckwheat (soba), served cold, dipped in a dashi and bonito broth. Once you’ve finished the noodles, pour sobayu, the water in which they were cooked, into the broth and sip, letting the warm saltiness percolate.

The noodles are handmade by Chef Shigeru Ide, who describes how he returned to the village – we’re still in Kawauchi, a few fields away from KiMiDori – only a month after the earthquake. He explains that soba production in the village used to be the second largest in Fukushima before the disaster. Now, five years on, business has contracted to 70 per cent of what it used to be. In response, the ancient tradition of soba-making, dating back to pre-Edo (pre-1600s) Japan, is being revisited to diversify production and thus, hopefully, attract new customers. So you can also munch on French soba galettes whilst sipping on a fresh and mildly peppery soba beer.

The fish served here is from adjacent Miyagi prefecture. Yet for most of the forty years of its operation the restaurant relied on the bounty of seafood caught off of the coast of Fukushima, no longer possible as the radioactive spillover into the ocean has caused continuing concerns about the radioactivity of fish. Owner Yamazawa Shigeru is a veritable sushi guru. He was among the first sushi itamae (cooks) to bring this delicacy to Europe. Here in the Odaka area of Minamisōma, the only part of the city where the evacuation order hasn’t been lifted (which will be lifted on the 12th of July), the restaurant’s main customers have been decontamination workers since it reopened in early 2016.

With a stern face, Yamazawa relives the day of the earthquake. Everything was shaking and people poured out onto the streets. He left Fukushima, not sure what was going on. Since returning and reopening the restaurant together with his son he’s back making delicious sushi, confident that thanks to locals’ support Urashima will maintain the standards of culinary excellence it has always been known for.

Yuko Hirohata founded a local newspaper, the Odaka Platform, to keep residents informed about the status of their town. She says this is important because everything has changed – and continues changing so fast. So much so that we shouldn’t call those who will be coming back to Odaka “returnees”, in her view, because this has become a “different place”. Rather, we should think of them as people who “choose” to live here.

She, like other Fukushima residents, wants the area to become synonymous with hope. The parallel with Hiroshima and Nagasaki is strong. The two cities, devastated by the atomic bombs that catalysed Japan’s surrender from the Second World War, are now thriving symbols of peace. The challenge for Fukushima residents is to change the world’s perception of this that is their home, from a place that evokes fatalism and fear, to one that inspires resilience and renewal. Because whatever you may think about what happened, why it happened and whether enough has been done since, the people of Fukushima deserve for their stories to be known.

Siamo anche su WhatsApp. Segui il canale ufficiale LifeGate per restare aggiornata, aggiornato sulle ultime notizie e sulle nostre attività.

![]()

Quest'opera è distribuita con Licenza Creative Commons Attribuzione - Non commerciale - Non opere derivate 4.0 Internazionale.

South African court dismisses a major lawsuit by 140,000 Zambian women and children against Anglo American for Kabwe lead poisoning. A setback for affected communities enduring the lasting impact of lead contamination.

Controversial African land deals by Blue Carbon face skepticism regarding their environmental impact and doubts about the company’s track record, raising concerns about potential divergence from authentic environmental initiatives.

Majuli, the world’s largest river island in Assam State of India is quickly disappearing into the Brahmaputra river due to soil erosion.

Food imported into the EU aren’t subject to the same production standards as European food. The introduction of mirror clauses would ensure reciprocity while also encouraging the agroecological transition.

Sikkim is a hilly State in north-east India. Surrounded by villages that attracts outsiders thanks to its soothing calmness and natural beauty.

Sikkim, one of the smallest states in India has made it mandatory for new mothers to plant saplings and protect them like their children to save environment

Chilekwa Mumba is a Zambian is an environmental activist and community organizer. He is known for having organized a successful lawsuit against UK-based mining companies.

What led to the Fukushima water release, and what are the impacts of one of the most controversial decisions of the post-nuclear disaster clean-up effort?

Nzambi Matee is a Kenyan engineer who produces sustainable low-cost construction materials made of recycled plastic waste with the aim of addressing plastic pollution and affordable housing.