By recovering clothes discarded in the West, Togolese designer Amah Ayiv gives them new life through his high fashion creations.

Two world-famous designers, Ross Lovegrove and Marcel Wanders, on the relationship between plastic and design. The stimulus for this conversation was offered by an exhibition at the past Milan Design Week inviting 29 designers to rethink their approach to this (now) demonised material.

During the last Milan Design Week in April, Rossana Orlandi presented the RO Plastic-Master’s Pieces exhibition to stimulate the design community to interrogate itself on the highly debated theme of plastics, promoting a more responsible use of these materials.

Dutch designer Marcel Wanders responded to the exhibition’s invitation with a message in favour of reusing (rather than recycling) plastic: he chose to display one of the elegant plastic water bottles designed by Ross Lovegrove in 2001 for Ty Nant, after having refilled it over 200 times in around three months.

We asked Wanders, considered the “master of aesthetics” advocating humanistic design thinking, and Lovegrove, pioneer in using technology in a way inspired by nature, to give us their view on the theme of plastics and design. Here’s what they told us.

Marcel Wanders, you chose to exhibit a disposable water bottle in the RO Plastic Master’s Pieces exhibition. Can you explain this choice?

MW: The exhibition suggests that we can freely use plastics without consequences as long as it is, or will be, recycled. I don’t want to recycle, I want to throw less away. I don’t believe there’s guiltless consumption. I disagree with Rosanna’s statement, there’s no guiltless plastic. Recycling ultimately legitimates consumption.

You’re one of the most provocative designers of our age, you design iconic objects and intelligent and sustainable products to bring inspiration to people’s lives: what do you think of plastic guilt?

MW: Modernism, still the most steering philosophy in design, considers the past irrelevant when creating the future, but what does that mean for the things we create today? It makes them irrelevant tomorrow. A world without past has no future. Modernism creates an endless stream of soon irrelevant and therefore disposable objects. Good design is an opportunity and therefore has the responsibility to combat waste, and there are many things designers do and can do better. We examine the materials we use in our designs more carefully. We’re creating knowledge and practices that make future products out of more intelligent materials while consuming less energy.

But investigating landfill shows that the larger part of products that we design are thrown away while still being functional. We don’t throw them away because they’re broken, we throw them away because our mindset is broken. It’s up to designers to proclaim and inspire for another relationship with our surroundings and behaviour.

Design is also expected to make people respect objects…

MW: Design and designers have the responsibility to influence the relationship between man and his manmade environment in a positive and holistic direction. For this task, designers can use their products, their speech, their writing or any influence they may have. Simply making things loved is a first fantastic ecological step. As designers we’re responsible for the technical and material consequences of our work, yet more than that, we have the responsibility to manipulate the psychological relationship our audience has with objects and their surroundings. In an age in which the pressure on physical resources is intensifying, it’s up to designers to come up with concepts that address the nature of our relationship with those resources.

We could say that there are no “wrong” or “right” materials, what is correct or not is behaviour. We need people to develop conscientiousness around plastics, rather than just reduce everything to the belief that it will all become ocean waste.

Ross Lovegrove, you’re one of the most innovative and unpredictable designers of our time. Do you think plastics are always evil, or simply misunderstood?

RL: Plastics are one of the most important contributors to civilisation from contact lenses, windows in aircraft, the packaging of blood and so on. So, removing intelligent use would be a disaster to our contemporary systems.

What must be addressed is the mindless and limitless production of cheap goods mainly in China and Asia, from toxic toys to cosmetic packaging, consumer durables like toothbrushes, lighters, flip flops, yogurt cartons, plastic bags and so on. We have to revert to using alternative materials that biologically conform to their use and lifespan so that they form part of a sustainable ecosystem. We had the Stone Age, the Bronze Age and now we have a Plastics Age … materials with their technologies which have kept pace with man’s evolution and population growth.

Lovegrove, should we always blame recycling as something that “legitimates consumption” as Wanders says, or should we just think about it under a different lens and explore new opportunities?

RL: I totally agree with Marcel and he’s made a very intelligent point in the debate. Recycling should be an integrated part of single-use material consumption, at a cost shared between the manufacturer and consumer.

There should be a UN of resource drawdowns and the monitoring of profiteering via a United Nations of Industrial Ecology. The problem should be dealt with at the source and not by volunteers collecting rubbish from beaches, waterways etc.; this is very empathetic but again legitimises the problem.

Do you believe design could make disposable objects last longer?

RL: Design can make things last shorter or longer depending on its own ecosystem. But it’s the sheer volume of online purchasing exacerbated by ease of consumption via Amazon, Deliveroo etc. that’s becoming a disease, the force of which goes against the tide of intelligent progress. In China they can even order a coffee online!

Wanders, what changes will occur in the near future?

MW: Recycling objects is a solution as well as a threat. There’s nothing recyclable about a great antique cabinet. Its fundamental functionality or dedicated craftsmanship, its embedded values or the timeless beauty it sustains, these qualities don’t make it recyclable, but make it live now and forever. Are we able to make the antiques of the future today? I don’t know, I’ll try. We need to build, educate and inspire our audience.

Do you think we’ll be saved by rigour and functionality, or by beauty?

MW: “If poetry is about love

and art is about love

and theatre is about love

and if opera is about love…

why do we think design is about…

functionality?” (one of his favourite quotes, editor’s note)

And if love was a country, beauty would be its ambassador.

View this post on Instagram

Lovegrove, if you had to design the Ty Nant bottle again today, what would you do differently?

RL: If I had to design a PET water bottle again I would either ensure that every last drop of water could be emitted, as nobody ever talks about the amount of water that gets held hostage in our landfill system. Or make my Ty Nant bottle thicker and stronger with a filter so that it naturally becomes reusable.

Wanders, if you had to design a water bottle, what would you do?

MW: I would, like always, search for the true human need behind the question. The true need is clean water and the certainty in having it. In the First World, instead of a bottle I would show my audience the sheer amount of water taps around them that can refill their reusable bottle. In other areas, I would build more taps or even clean the water first. People don’t need disposable bottles, they need water.

Do you think we may continue using plastic water bottles in the future?

MW: We won’t use disposables because they’re use-less. We’ll reuse items because they’re use-full.

Lovegrove, many of your projects represent the perfect dialogue between nature and technology, like the Bamboo Bike for Biomega. Many others, like the Supernatural Chair, have plastic at their core. Do you think these types of projects will still represent you in the near future?

RL: My Bamboo Bicycle for Biomega was just a symbolic gesture towards changing our mindset towards mobility, it never really made an impact commercially. It was design to break the perception of design as always being high-tech and urban, thus bringing in a very sustainable message from more modest tropical origins. My Supernatural Chair for Moroso used less than half the material of its nearest competitor via gas injection and the organically essential lines of its form. The holes weren’t intended as decoration but to liberate its mass from unnecessary amounts of material, a principle I practice in design.

Ultimately, it’s about delivering a subtle message about limiting excess, not a prescriptive one, but just there as a mandatory part of my own process. I like a “fat free and fit” design, but that’s all relative to emergent aesthetics and typologies … but these principles applied to high volume industries such as the automotive, aerospace, consumer electronics, portable device ones, etc. are extremely important. Not so much grounded in residential products and furnishings.

What’s your best project using plastic?

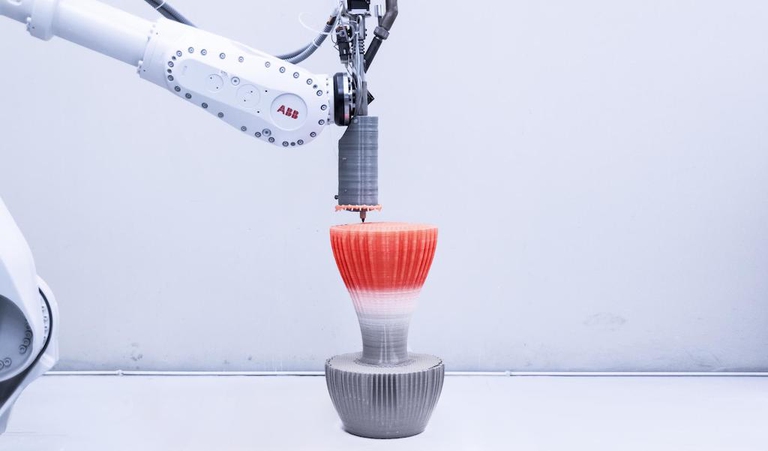

RL: I’m currently involved in the pioneering of the 21st Century revolution in additive technologies: 3D printing to achieve a sincere trinity between material mass, function, time and energy. This field I believe is the natural and economic antidote to quickfire mass consumerism, replacing ubiquitous dull disposability with a new value system that yields biodiversity and intelligent resource use across the board from biotech, to aerospace, to automotive and even products closer to the consumer food chain. The illustration I give for the moment is my work for Nagami, a Robotic 3D printing startup in Spain of which I’m the main design consultant. Nagami is involved in furniture, lighting, objects and interiors all using state of the art software and robotics.

Wanders, you describe yourself “shaping the design industry”, discovering new materials and pushing the boundaries of how things are made and used. Projects like the O2SafeAir mask, the world’s first made from all-natural materials, or Wattcher, the energy monitor you designed in 2009 to track domestic electricity use, embody your attitude towards innovation and stimulating awareness. What’s your most representative project aimed at pointing out new behaviours?

MW: In the inflight service we designed for KLM’s business class, we replaced the disposable plastic bowls with a ceramic bowl. This keeps the content of the food fresher, is more economic and prettier, and saves a huge amount of CO2 due to its lower weight on every flight. The weight alone already made an immense contribution to KLM’s sustainability promises. The disposable bowl was set in a controlled ecosystem where all bowls were recycled and reused. After an independent investigation in a plane we were able to prove to KLM that water in their planes boils around 89 degrees Celsius. With that information we were able to convince the airline to replace their plastic disposable coffee service with a more lightweight and prettier biodegradable one. Behaviour is supported by convictions. And convictions are more dangerous enemies of truth than lies, as Friedrich Nietzsche taught us.

What’s your favourite material, if you have one?

MW: Grey mass. Our brain. That’s the only material that counts in the world.

RL: Human living skin.

What message would you share about the future of plastics with our readers?

MW: I’m proud to be part of a community of creators who are considering and re-considering the results of their professional actions. My goal, like many others, is to fight our current throwaway culture. We’re aware of our actions and we share the responsibility to improve our long-term positive relationship with our man-made surroundings. Only then will we have a positive long-term relationship with the world.

RL: “Life on a planet comes of age when it first works out the reasons for its own existence”.

Siamo anche su WhatsApp. Segui il canale ufficiale LifeGate per restare aggiornata, aggiornato sulle ultime notizie e sulle nostre attività.

![]()

Quest'opera è distribuita con Licenza Creative Commons Attribuzione - Non commerciale - Non opere derivate 4.0 Internazionale.

By recovering clothes discarded in the West, Togolese designer Amah Ayiv gives them new life through his high fashion creations.

All catwalks in July will be broadcast online: after Paris, it’s Milan Digital Fashion Week’s turn. And the biggest beneficiary is the environment.

The book Fashion Industry 2030 aims to contribute to reshaping the future through sustainability and responsible innovation. An exclusive opportunity to read its introduction.

From fashion to design, from architecture to construction, biomaterials and their applications are constantly multiplying. And designers are responding to this revolution in many different ways.

A new study on linen, presented at the Milano Unica trade show, highlights the material’s numerous advantages and low environmental impact.

Victor Papanek spearheaded social and sustainable design based on political awareness rather than consumerism. A biography of the author of Design for the Real World.

Getting people to consume less is important, but it’s not enough. There has to be a cultural shift, and design is likely to have a key role in transforming our approach to plastics.

A journey to discover leather tanneries in Dhaka, the capital of Bangladesh, among terrible working conditions, pollution and laws left unenforced.

Yona Friedman is a visionary and innovative architect and theorist. We met him during the inauguration of the installation he made in occasion of the Milan Design Week.