Three people putting the protection of the planet before themselves. Three powerful stories from Latin America, the deadliest region for environmental activists.

The Bakken or Dakota Access Pipeline (DAPL), an underground oil pipeline project in the United States, is owned by a network of oil and pipeline companies, joint ventures and holding companies. After Trump revived it in January without the consent of the Sioux indigenous tribe affected by it and flouting environmental laws, many investors both from the US

The Bakken or Dakota Access Pipeline (DAPL), an underground oil pipeline project in the United States, is owned by a network of oil and pipeline companies, joint ventures and holding companies. After Trump revived it in January without the consent of the Sioux indigenous tribe affected by it and flouting environmental laws, many investors both from the US and abroad have urged banks to either support rerouting the pipeline or divesting from it. The project is highly controversial because it would affect the Standing Rock Native American reservation between North and South Dakota, violating tenets of the UN Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples including the right to health, to water and subsistence, free prior and informed consent, protection against threats to sacred sites including burial grounds, treaty rights and cultural and ceremonial practices.

Energy Transfer Partners, company that owns a diversified portfolio of energy assets in the United States, and its subsidiary Sunoco Logistics currently own almost 38.25 per cent of the pipeline; MarEn Bakken Company LLC, a joint venture between Enbridge Energy Partners and Marathon Petroleum Company, owns 36.75 per cent of the pipeline; and a subsidiary of energy manufacturing and logistics company Phillips 66 owns the remaining 25 per cent of the project.

In March, Dutch bank ING Groep became the first out of the seventeen banks to offload its debt from DAPL, selling 120 million dollars in loans from the Dakota Access pipeline. A few days later, Norway’s largest bank DNB issued a statement that it was selling more than 331 million dollars in loans to build the pipeline, which is close to 10 percent of the cost of the project. Norway’s largest private investor Storebrand, with 68 billion dollars in assets, sold 34.8 million dollars worth of shares in DAPL of Phillips 66, Marathon Petroleum Corporation and Enbridge on the 1st of March. The divestment was a “last resort” measure after Storebrand attempted (unsuccessfully) to influence the pipeline’s route by directly reaching out to the companies. Other investors like mutual fund Odin Fund Management also decided to sell their shares worth 23.8 million dollars in companies connected with the pipeline in November 2016. Similarly Swedish bank Nordea banned investment in Energy Transfer Partners, Sunoco Logistics and Philips 66 from its portfolio after the companies declined any form of dialogue to create an alternative pipeline route and German bank Bayern LB is also reportedly seeking to divest from the pipeline.

We hope that our actions and the actions of other likeminded investors in either divesting or calling for an alternative [pipeline] route will make some sort of an impact. The signal effect shouldn’t be underestimated. Even if it’s too late for Dakota Access, the very fact that there is so much noise and so much protest will make companies with future projects take more seriously indigenous peoples’ rights and environmental concerns. (Matthew Smith, Storerand head of sustainability)

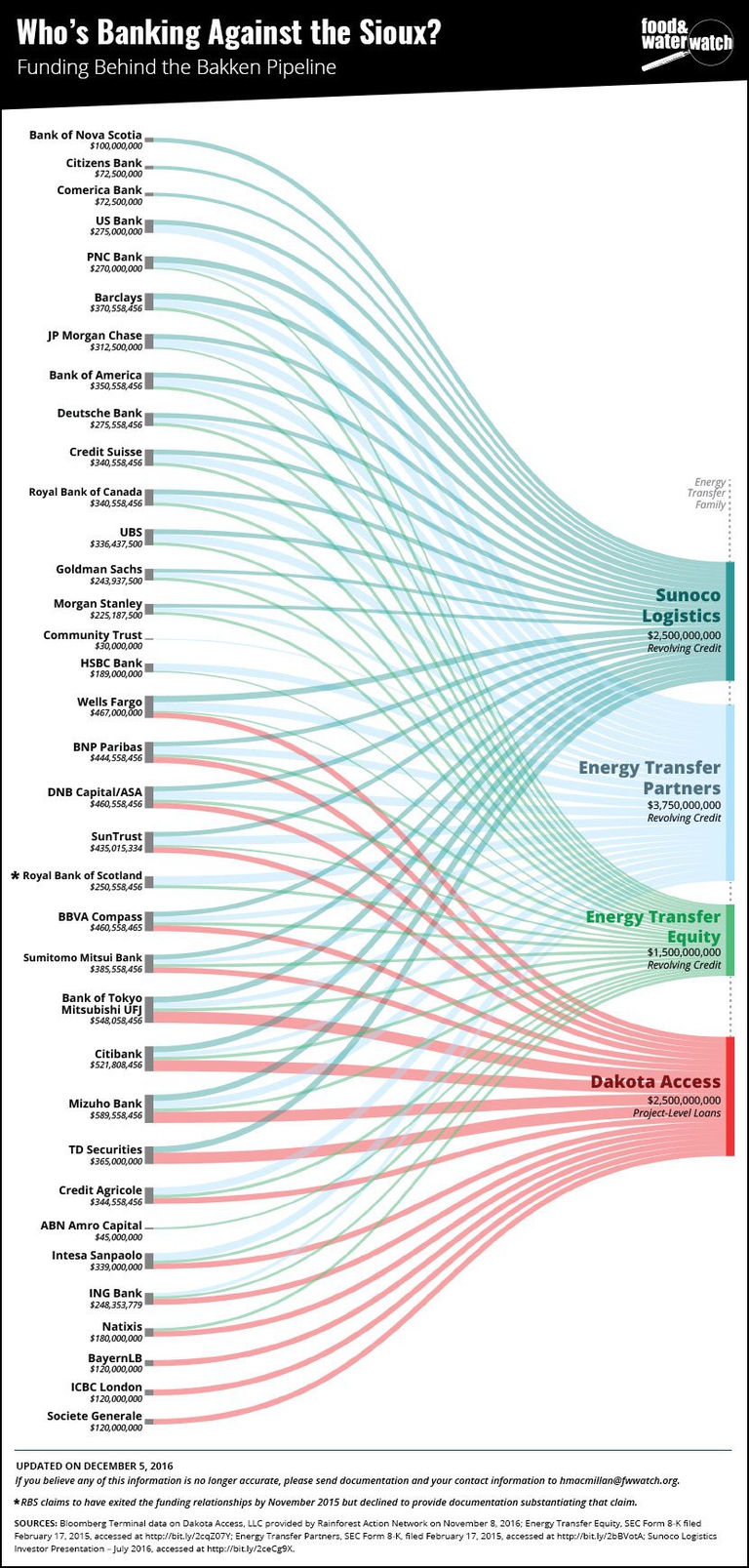

In February a group of around 120 investors with a combined 653 billion dollars in managed assets told the banks financing DAPL that the project should be rerouted away from the Native American reservation. These included CalPERS, which manages the largest public pension fund in the United States, as well as asset management firms and religious organisations. In the statement investors expressed their concerns: “If DAPL’s projected route moves forward, the result will almost certainly be an escalation of conflict and unrest as well as possible contamination of the water supply”. The banks it was addressed to include:

Under the Defund DAPL slogan activists have campaigned for individuals and institutions to move money out of the banks funding the pipeline. This resulted in Seattle city council voting to not renew its 3 billion dollars worth contract with Wells Fargo over the bank’s involvement. The Californian city of Davis has also divested from Wells Fargo after its council unanimously voted to find a new bank to handle its finances. Other cities including San Francisco, Santa Monica, Boulder, Minneapolis, Philadelphia and Portland are reportedly considering similar measures.

The Defund DAPL campaign estimates that individuals have pledged to withdraw more than 70 million dollars from financial institutions doing business with the pipeline’s owners. Another significant way to divest money from companies associated with DAPL is OpenInvest, a tech startup that has designed a feature that automatically pulls companies funding the pipeline out of your investment portfolio rebalancing it with new investments.

Surprisingly many of the banks funding DAPL (including ING and DNB who were previously financing the project) are signatories to the Equator Principles (EPs), the global best practice standard for assessing and managing environmental and social risks in project financing. In November a consortium of civil society groups including Bank Track wrote an open letter to the EP Association expressing concern that 13 Equator Principle Financial Institutions (EPFIs) are involved in a credit agreement with Dakota Access LLC and Energy Transfer Crude Oil Company LLC to borrow up to 2.5 billion dollars for the pipeline’s construction and an additional 8 EPFIs are providing further credit to the project sponsors. This is contrary to Equator Principle 5 on stakeholder engagement that specifies that, “projects with adverse impacts on indigenous peoples will require Free, Prior and Informed Consent“.

Lawrence Summers, ex-chief economist at the World Bank, once stated in an infamous memo, “the economic logic of dumping a load of toxic waste in the lowest-wage country is impeccable and we should face up to that”. Applying the same rationale to poorer areas in the United States, it is clear that banks and investors associated with DAPL continue to give importance to corporate profits over human rights. However in the face of staunch and unprecedented protests against the project, involvement in this project may not make much business sense. Banks with financial ties to the pipeline may lose customers as well as creditors and face long-term brand and reputational damages resulting from consumer boycotts and potential legal liability. The investors who are the major shareholders in these banks may also be impacted by the reputational and potential financial risks. Though it might be too late to stop DAPL, it might nonetheless prove to be significant in deterring companies from investing in projects violating indigenous peoples’ rights in future.

Siamo anche su WhatsApp. Segui il canale ufficiale LifeGate per restare aggiornata, aggiornato sulle ultime notizie e sulle nostre attività.

![]()

Quest'opera è distribuita con Licenza Creative Commons Attribuzione - Non commerciale - Non opere derivate 4.0 Internazionale.

Three people putting the protection of the planet before themselves. Three powerful stories from Latin America, the deadliest region for environmental activists.

Influential scientist, activist and author Vandana Shiva fights to protect biological and cultural diversity, and against GMOs.

Kimiko Hirata has blocked 13 new coal plants in Japan, but she hasn’t done it alone. The 2021 Goldman Prize winner tells us about her movement.

The Goldman Environmental Prize, the “green Nobel Prize”, is awarded annually to extraordinary activists fighting for the well-being of the planet.

We talk to Shaama Sandooyea, activist and marine biologist from Mauritius onboard Greenpeace’s Arctic Sunrise ship in the heart of the Indian Ocean.

Arrested for supporting farmers. The alarming detention of Disha Ravi, a 22-year-old Indian activist at the fore of the Fridays for Future movement.

Water defender Eugene Simonov’s mission is to protect rivers and their biodiversity along the borders of Russia, China and Mongolia.

Chibeze Ezekiel, winner of the 2020 Goldman Environmental Prize for Africa, is fighting to guide new generations towards a renewable future.

Leydy Pech, winner of the 2020 Goldman Environmental Prize for North America, is the beekeeper who defended Mexican Maya land against the agro-industry.