A group of experts in Tokyo suggested pouring radioactive water from Fukushima into the open sea. A marine biochemist explains the consequences of this absurd decision.

Japan is the first country to experiment mining deep-sea hydrothermal vents. These hostile yet unique habitats are rich in life and precious minerals, leading to interest in both researching and mining them.

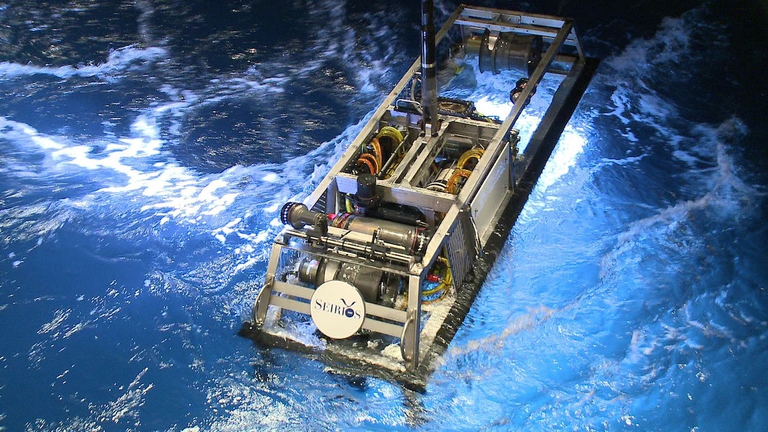

Hydrothermal vents are a relatively recent discovery dating back to the late 1970s: around 500 are estimated to exist globally and up to now limited scientific research has been conducted on them. These chimney-like structures form when underwater volcanoes release magma and minerals into near-freezing seawater, which then solidify into the iconic shape. They’ve been found to be a rich source of minerals such as gold, zinc, nickel and copper, all useful to the production of electronics. The constantly rising demand for these has led some countries to begin investing in deep-sea mining technology. This year Japan became the first nation to successfully mine zinc and other minerals from deep-sea vents, confirming the possibility of exploiting this untapped source.

Read more: Seabed mining, it could be coming to an ocean near you

Scientists have discovered that hydrothermal vents are the natural habitats of an abundance of endemic wildlife supported primarily by a specific type of bacteria known as chemoautotrophic. Each vent has been shown to present a unique ecosystem inhabited by creatures withstanding extreme pressure, high temperatures (370 degrees Celsius and above), toxic materials and total darkness, living off the energy formed by the chemical processes triggered by these unique formations. Thanks to the highly specialised bacteria larger species such as zooplankton, shrimp and tubeworms thrive in these harsh conditions, which can support even larger creatures such as siphonophores, crabs and even octopuses.

It’s begun: first large-scale mining operation launched in the oceanhttps://t.co/2DAeTtRMY3#deepsea #deepseamining #seabedmining #japan pic.twitter.com/gl2ikCjZVs

— UCSB Benioff Oceans (@UCSBenioffOcean) 27 settembre 2017

According to a review published in the American Geophysical Union the life span of these fascinating geological formations is varied: with some vents appearing to last centuries and even millennia, and others being repeatedly destroyed by volcanic eruptions. Incredibly, such vents have been observed to reactivate and begin spewing out materials a mere decade after total devastation, with fauna coming back to populate these volatile neighbourhoods.

Read more: Calling all ocean lovers, it’s time to act against seabed mining

Since mining would involve crushing and grinding rock with machines to then be sucked up into ships floating above water, the most immediate environmental impact would include the degradation of hydrothermal vents. Additionally, similar operations such as Carmichael in Australia, a coal mining project set to threaten the Great Barrier Reef, adopt a filtering strategy whereby the desired materials are sifted out of the remaining 90 per cent of unwanted debris, which is then placed back down into the sea depths, where it deposits as sediment. This may pose a further threat to an already stressed ocean system and has so far received strong criticism.

Adding salt to the injury, some studies have detailed another benefit of hydrothermal vents, which act like a “plumbing” system to help regulate oceans’ chemical composition across the globe. This suggests that destroying these irreplaceable environments might have an even more profound impact. Yet the International Seabed Authority (ISA), which regulates all mining activities that concern seabeds in international waters, has already given permission to 25 countries (including Japan, Russia and France) to carry out deep-sea mining. No commercial operations have begun just yet but it is estimated that by the mid-2020s large-scale mining enterprises could become a reality.

The Wild West of Deep-Sea Mining https://t.co/AcIS4VNzJC — DeepSea Mining (@oceanmining) May 19, 2017

Three main issues are immediately apparent: the important role that the ISA should play to safeguard these unique habitats, how protective regulations (once in place) would be enforced in non-international waters, and understanding just how much these ecosystems are in danger. What seems to be lacking the most is research to base any decision upon, although with time and proper resource allocation this issue may be solved. Unfortunately, at the current pace of affairs, there may not be much time left.

Siamo anche su WhatsApp. Segui il canale ufficiale LifeGate per restare aggiornata, aggiornato sulle ultime notizie e sulle nostre attività.

![]()

Quest'opera è distribuita con Licenza Creative Commons Attribuzione - Non commerciale - Non opere derivate 4.0 Internazionale.

A group of experts in Tokyo suggested pouring radioactive water from Fukushima into the open sea. A marine biochemist explains the consequences of this absurd decision.

The decline in grey and humpback whales in the Pacific and Atlantic Oceans has been traced to food shortages caused by rising ocean temperatures.

The United Nations has launched a major international alliance for ocean science, undertaking a mission close to all our hearts.

The cargo ship that ran aground off the coast of Mauritius on 25 July, causing incalculable damage, has split in two and its captain has been arrested.

The largest coral reef in the world is severely threatened by climate change, but researchers are developing strategies that could contribute to saving the Great Barrier Reef.

Seychelles have extended its marine protected area, which now covers over 400,000 square kilometres, an area larger than Germany.

Norwegian oil giant Equinor had pulled out of drilling for oil in the Great Australian Bight, one of the country’s most uncontaminated areas. A victory for activists and surfers who are now campaigning for the area to be protected forever.

30 per cent of the planet needs to be protected to stop precipitous species decline. The UN has set out its aims for the the COP15 on biodiversity scheduled for Kunming, China in October.

Ocean warming has risen to record highs over the last five years: just in 2019 the heat released into the world’s oceans was equivalent to that of 5-6 atomic bombs per second. The culprit, no doubt, is climate change.