A special report from the Yuqui territory delves deep into the dreams, challenges, joys and sadness of one of Bolivia’s most vulnerable indigenous groups.

The tribes of the Lower Omo Valley in Ethiopia live in close contact with nature and the river they depend on. But their ancestral ways of life are being threatened by the impacts of a mega-dam, climate change and a booming tourism industry.

A mother holds her son’s head, the boy is no older than two years old, inside a goat’s stomach. After a couple of minutes, he resurfaces as if out of water. He isn’t wet but his skin in covered in what the animal ate before dying – semi-digested grass – which his mother smears on his feet as if performing a cosmetic treatment. Then she gives him a piece of the stomach to chew on.

To undestand the lifestyles and worldviews of the tribes of the Lower Omo Valley in southwestern Ethiopia, first we must suspend all judgement. The ritual described may seem cruel but the child is peaceful and like the rest of the Hamer tribe his mother believes this act, which would be considered a form of violence elsewhere, can protect him from malaria. If anything, it serves to prepare him for a hard life of daily toil and suffering. What’s important isn’t to establish what’s right and what’s wrong, but gain a clearer picture to understand whether these peoples’ ways of life should be preserved. And, more importantly, who gets to decide.

We use water from the river. Before it was full but now there’s less, I don’t know why. Lorogue, Dassanech tribe elder

“Everything has changed in the past few years,” says tour guide John Lomala of the Dassanech, 48,000 people living along the Omo River and one of the area’s most populous tribes. The Lower Omo Valley is home to a total of 200,000 indigenous inhabitants divided into pastoralist tribes whose roots, languages, customs, cultures and physical appearance differ from one another, as do their agricultural systems. Eight groups were officially recognised in the government’s 2007 census, the last, but many anthropologists speak of greater numbers: from twelve to sixteen, to a couple dozen tribes. In Ethiopia, described as the “museum of peoples” by early 19th century Italian historian Carlo Conti Rossini, there are more than eighty ethnic groups.

90,000 people live along the banks of the Omo River and depend on its natural cycle of seasonal floods to fertilise the soil. The river, whose source lies at 2,400 metres in altitude, runs for 700 kilometres until il reaches the Turkana, the largest desert lake in the world, at 100 metres above sea level, marking the passage into Kenya. The river is a vital source of sustenance for the inhabitants of this area, which is unique for its high concentration of native populations who “still live fully in contact with nature, like humans did 3,000-4,000 years ago,” says Giovanni Miceli, a tour operator who has been travelling to Ethiopia for over a decade and who founded the NGO Barjo Imè to provide assistance to three villages of the Hamer tribe.

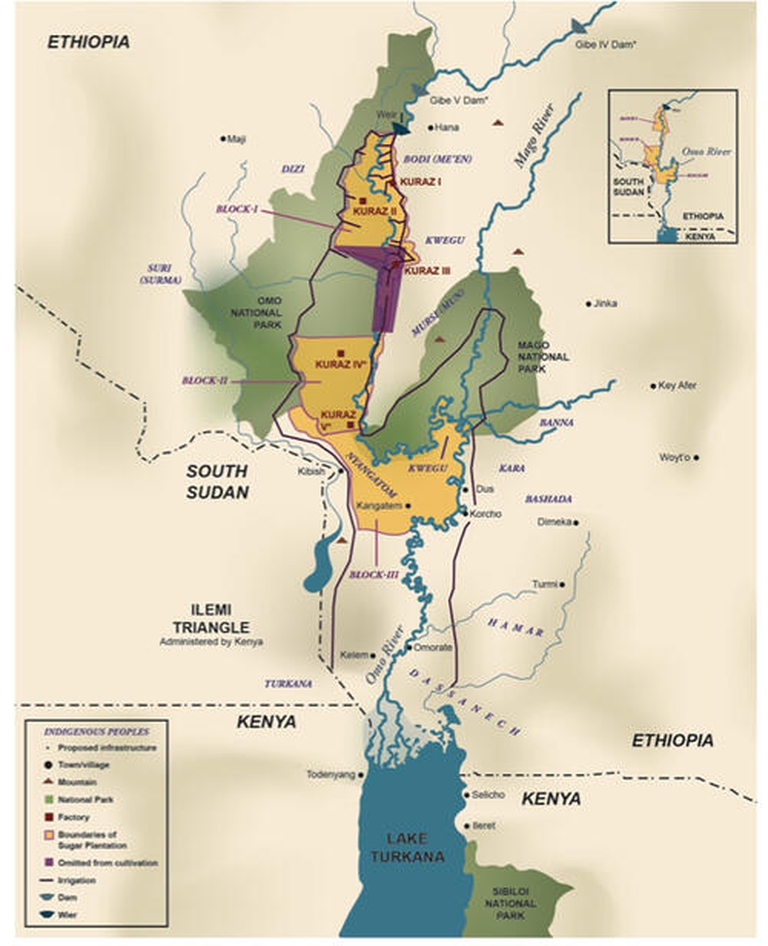

Yet seasonal floods have ceased due to a massive hydroelectric project – five dams in total, two of which are due to be completed – which has led to communities’ eviction from their land and increased their reliance on rain-fed (rather the flood-fed) agriculture. Food insecurity has resulted from the impacts of climate change, which has caused alterations in rain patterns, longer droughts and a higher frequency of unexpected, powerful floods. “The river used to be very full but for a few years now we haven’t been able to cultivate the banks,” explains Damo Dori of the Kara, one of the smallest tribes in Africa, with around 1,500 members. The origins of this sudden change are to be traced to the first dam built on the Omo, Gibe III, in 2016.

The dam, no question, is very important for the country: it produces electricity, therefore hard currency. But it needs to be managed properly to benefit the tribes as well. Yonas Mahetemu, founder of Bella Abissinia, an Addis Ababa-based tour operator

The dam is an important source of hydroelectric energy and water used to irrigate industrial sugarcane and cotton fields. “In the absence of oil or gas, Ethiopia’s most precious resources are water and land,” Mattia Grandi, researcher at the Sant’Anna School of Advanced Studies in Pisa, Italy, points out. With a huge hydroelectric potential, second on the continent, the country has decided to invest in this renewable energy source to feed its burgeoning GDP, which has grown up to 10 per cent annually in recent years, and a 15 per cent increase in energy demand (though two thirds of the population remain disconnected from the grid).

The current government led by Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed Ali, known as Abiy, who came to power in April 2018, has continued supporting massive hydroelectric projects such as the Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam (GERD) on the Nile, which will become the continent’s largest, as well as Gibe III, the tallest dam in Africa with its almost 250 metres in height. Therefore, the administration has put its “political weight behind building a development model based on the regional trade in energy, which is sold to neighbouring countries,” Grandi contextualises.

I don’t know anything about the dam.Lorogue, Dassanech tribe elder

Gibe III’s name comes from the Omo affluent on which first two hydroelectric turbines, Gibe I and Gibe II, were completed in 2004 and 2010 respectively. All the structures were built by Italian company Salini Impregilo, currently involved in the construction of the Gibe IV or Koysha dam, as well as GERD. “Salini is basically the Ethiopian government’s operational arm with regards to hydroelectric development,” writes Emanuele Fantini of the IHE Delft Institute for Water Education in The Netherlands.

My people have no idea about the dam, they’re saying God is punishing them.John Lomala, Dassanech tour guide

The second Gibe was financed directly by the Italian Ministry of Foreign Affairs, a decision that “was met with a great deal of criticism and in light of which a study conducted by the country’s national development agency suggested that the government suspend financing of successive dams,” Grandi explains. Controversial aspects were highlighted such as “the anomaly of granting Salini the contract through a direct negotiation” and “the inadequacy of the environmental impact study”, as mentioned in a 2010 Italian parliamentary inquiry into the ministry’s actions.

Gibe III, funded by the Industrial and Commercial Bank of China with the World Bank’s contribution for building the transmission lines, also came under fire due to the absence of an independent Environmental and Social Impact Assessment (ESIA). “It’s not true that it wasn’t carried out,” Grandi clarifies. “Simply, the government’s 2006 ESIA, updated in 2009, was conducted by Italian consulting firms,” therefore potentially close to Salini’s interests.

I know about the dam on the Omo River.Allo Shada, Hamer tribe

“The inhabitants of the Omo Valley have been deprived of their land as well as access to water and the river especially due to the plantations,” Grandi points out. The conversion of hectares of savannah into large fields began in 2011 when fertile plots, some of which occupied by villages, were given to foreign investors and destined to become part of the government-owned Omo-Kuraz Sugar Development Project (KSDP) for the cultivation and processing of sugarcane: initially allocated 245,000 hectares, its projected size was reduced to 100,000 hectares.

I’ve heard about the dam and plantations, but I’ve never seen them.Damo Dori, Kara tribe

An ambitious project aiming to transform the Omo Valley into an agro-industrial export hub whose political and economic relevance was made clear when both Abiy and Eritrean president Isaias Afewerki attended the inauguration of the Omo-Kuraz III factory, built with a loan from a Chinese bank, in October 2018. Organisations such as Human Rights Watch accuse the government of having violated its duties by failing once again to publish an ESIA and create the employment opportunities the tribes were promised. Only 4 per cent of the 700,000 new jobs estimated by the Ethiopian Sugar Corporation, owner of the Omo-Kuraz factories, has materialised according to data from 2016. Furthermore, many of these seasonal and low-paid positions have been assigned to migrants from other parts of the country.

My family depends on livestock. If I work on the plantations I can survive, but if all the grazing land is taken what will my family do?John Lomala, Dassanech tour guide

There are fewer trees, less rain and harvests are smaller. Maybe there isn’t enough water in heaven.Urmale Guyta Orgawa, Konso ethnic group

The social and environmental fallout of the hydroelectric projects and connected industrial agricultural complex can’t be isolated from the wider effects of global warming, which is having profound effects in the Horn of Africa. Average temperatures in the Turkana basin have already increased by 2-3 degrees Celsius since the 1970s. Over this period, the lake, a considerable part of which used to be in Ethiopia, has shrunk up to the border with Kenya. “Today, drought has become an annual feature in the region, but it used to happen just once every four years,” says Paul Obunde of Kenya’s National Drought Management Authority. Seasonal rain patterns have also changed, as the inhabitants of the Omo Valley describe: “The rainy season used to be four months long, now it only lasts two months,” says Damo Dori and, “while there used to be three rainy seasons, now there are only two,” according to Dassanech tribe elder Lorogue. “And there’s also more drought,” he adds.

We’re not yet getting it right in terms of Eastern Africa’s humanitarian response to drought. We’ve not taken a long-term development approach. Billions of dollars flow into these countries. Is it effective? No, because the drought is coming again.Jeanine Cooper, Agriculture Minister of Liberia and ex-head of the UN Office for Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs in Kenya

Rising temperatures and lack of water have pushed pastoralists to compete for reduced grazing land, leading to its over-exploitation. A scenario compounded by the interruption of the Omo’s regular seasonal inundations because of the dams, notwithstanding the (until now empty) promises on the government’s part that the lands adjacent to the river would be irrigated by artificial floods.

Furthermore, the filling of the Gibe III basin caused the level of the Turkana, which receives 90 per cent of its water from the Omo, to decrease by up to 1.5 metres between 2015 and 2017; the level of the lake, whose average depth is of 30 metres, could be reduced by 10 to 20 metres according to University of Leicester hydrologist Sean Avery. The resulting increase in the water’s salinity as well as fall in the nutrients transported by the river could halve the biomass of the lake in which over sixty fish species, ten of which endemic, live, and fishing could be reduced by two thirds. In light of this situation, Unesco has added Lake Turkana to the list of World Heritage Sites in Danger.

Private property of land doesn’t exist in Ethiopia. Instead, the government gives the right of usufruct, usually for 99 years. Expropriation hasn’t only led to the loss of usufruct rights but also the possibility of selling them.Mattia Grandi, researcher at the Sant'Anna School of Advanced Studies in Pisa

The Lower Omo Valley is a frontier not only because it borders with Kenya but because its tribes live on the edge of modernity – a term used neutrally here, stripped of positive or negative connotations. The Gibe dams and industrial plantations represent a bold step in its integration into a modern national development model, though resource scarcity remains a problem. For example, the tribes, whose diet is based on maize and sorghum flour, don’t have enough food, says Chao Dro of the Arbore tribe, with a population of around 6,000 to 7,000 people. In this context, some state that they receive food aid from the government, though Lorogue laments the fact that this has arrived only once over the course of two years. Others point out that they don’t receive any help, according to Oruduru, village head of the Mursi tribe, numbering around 10,000 people.

Our village was on really fertile land so we had to move for it to be given to investors for farming. The elders resisted but government officers took them to town and when they got back, we had to move.John Lomala, Dassanech tour guide

In part to mitigate the stress on agricultural systems, the government has tried to relocate some villages, especially those around the Omo-Kuraz hub, a policy known as villagisation, which “also aims to provide services in places where there aren’t any roads,” Grandi explains. “However, this means altering the way of life of entire populations,” and the authorities have responded to the tribes’ resistance with violence, Grandi adds. “Widespread human rights abuses have been reported, including forced evictions, the ploughing of ripening crops, beatings and rape,” according to think tank Oakland Institute’s report published last year. “Seeing as the tribes’ settlements are essentially always small, the news (of violence and forced evictions, ed.) has reached us only a fraction of the times it’s actually happened,” Miceli contextualises.

Furthermore, the government’s interventions to teach tribes agricultural skills haven’t been successful, seeing as “in some areas these have been learnt but productivity remains low, and in others such skills haven’t been acquired at all,” Miceli explains. Many of these communities, in fact, still rely on food aid even if they’ve been allocated plots of land. But these are too small and lack adequate services, the Oakland Institute points out. For example, the “government promised the Dassanech and all the tribes along the Omo River – the Kara, Nyangatom, Mursi and Kwegu – that each village would receive a water pump for irrigation,” Lomala recounts. “We only have two water pumps in two villages and we are 52 villages. The government should keep its promises”.

When there’s drought we don’t have enough food so we exchange our goats for sorghum and maize. If the drought becomes severe we move our livestock to where there’s water, such as along the Omo River. This causes conflict with the Dassanech as they don’t want us to use their land as pasture.Allo Shada, Hamer tribe

Conflicts between tribes have worsened. “The degradation of pastures has caused a rise in episodes of plundering,” Grandi explains. “These have always occurred, as in any nomadic society, but the last ten years have been particularly critical”. For example, 65 members of the Kenyan Turkana tribe died in a single attack at the hands of the Dassanech in 2011 and 100 members of the Ethiopian tribe were killed in retaliation. In 2015, local media reported the killing of 75 people overall and the theft of 25,000 animals.

There’s no fish because the drought made everybody become fishermen. The fishermen of Turkana, they come, they want to fish here. Of course, it’s Dassanech land. The Dassanech want to come and fish here, so they don’t want the Turkana fishermen to fish here, then they have to fight them to chase them away.John Lomala, Dassanech tour guide

The fight for resources between the Dassanech and Turkana has been described as one of the world’s first climate change conflicts, in the words of a UN official. “The countries are continually introducing programmes to bring peace,” says Patrick Devine, co-founder of the Shalom Center for Conflict Resolution and Reconciliation, “but they don’t have sufficient institutional mechanisms to control the conflict”. In this context, a lot of expectation is falling on Abiy’s shoulders, especially after being awarded the Nobel Peace Prize “for his decisive initiative to resolve the border conflict with neighbouring Eritrea”. But, in Lomala’s words, the prime minister is “far from the tribes, and now he’s busy with the settlement of his new government”, as well as ferocious internal political battles. “I don’t blame him for what’s happening to us, we need to give him time, he might be able to help us,” Lomala adds, hopeful.

The government is engaged in disseminating the national curriculum by supporting the development of a capillary education system, a topic dear to it, Miceli explains. “When I was in school, we used to walk for two days across the bush,” recounts Ariyo Dore Zusay of the Kara, a local administrator and the Head of the Education Office for the Hamer district, “now it’s easier because the government has built new schools in more remote areas. We’re trying to serve all villages by giving them access to alternative basic education and mobile schools”. But obstacles are significant as “parents are substituting the work of children to send them to school, but there’s high dropout because of drought, mobility and internal conflicts between tribes and clans”.

“Some families take the children away from class and send them into the fields to take care of the goats,” teacher Sister Messele explains. “We’re trying to convince parents to let their children attend class at least two to three hours a day”. The teacher works in a small school in the Hamer village of Labella built by the Italian NGO Barjo Imè, founded by Miceli in 2016 to give access to water and education as well as emergency relief to this and other two of the tribe’s villages. “It was simple to think of education as a tool to put in their hands,” Miceli clarifies. “We chose a village, the one furthest from town, with the poorest access to services and we gave it a school, a walled structure with two classrooms, for now”. This means the children don’t have to walk for miles every day to receive an education.

“The first year there were few students, but the next year there were 21 and now there are 35,” Sister Messele says, proudly. She teaches the national curriculum and lives in a house built by the NGO. “To the tribes, schooling means understanding how to live: for example, children who attend class are better equipped to protect themselves from diseases,” comments Yonas Mahetemu, founder of Addis Ababa-based tour operator Bella Abissinia, a friend and colleague of Miceli’s who manages the charity in Ethiopia. In addition, education offers even wider prospects. “I decided to send my son to school because times have changed,” explains Esta Shada, who has also started attending class because he believes this can give both him and his son a better future.

Education can be especially transformative for girls. The rate of female education in the area is very low, around one in four students are girls, Zusay explains. “It’s difficult for the tribes to send girls to school because they’re an asset; when they get married families receive cattle and goats as dowry,” Messele points out. Furthermore, in certain tribes “it’s strictly forbidden to send girls to school,” Chao Dro specifies, therefore you can’t push anybody. Mahetemu believes that families will start sending their daughters to school once they understand how important education is.

Things are changing, slowly. The Labella school is attended by three girls and there are mothers such as Allo Shada who are breaking down barriers. She was the first in the Hamer village of Arna to send her daughter to school to give her a better future. “I don’t know what she can become as I’ve never been to school. She’ll decide herself as she grows up,” Shada explains.

As the tribes increasingly come into contact with ‘us’, the government and urban society, they start wanting cell phones, clothes, sunglasses, jeans and shoes. I don’t think there’s anything wrong with that, it’s a process we also went through. However, what is wrong is the speed at which it’s occurring, which is accelerated compared to a natural progression.Giovanni Miceli, tour operator and founder of the NGO Barjo Imè

“Our role should be that of bringing the benefits of our civilisation and help the tribes make their life a little easier and their future a little brighter, while at the moment we’re running the risk of intervening too forcefully,” Miceli points out in reference to the changes brought out by a relatively new phenomenon. Tourism, which began in earnest in the 1990s, has grown five if not six-fold according to Miceli. “I started coming to the Omo Valley fifteen years ago,” Mahetemu recounts, “the tribes were very wild and there were few tourists. But in the last six to seven years, the road was changed to asphalt and now there’s easy access because of the airport”.

“Years ago, people in the villages would run away from visitors,” adds Dinote Kusia Shenkere, guide of the Konso ethnic group, whose territory is adjacent to that of Omo tribes. “So we started giving things to children for them to get closer to tourists. People hated cameras because they thought they would take their soul, now they want their photos to be taken in exchange for money”. Alala, wife of the Mursi village head Oruduru, points out that the money paid by tourists is used for food. And whilst “we cultivated the riverbanks beforehand, now we have money to buy flour,” says Damo Dori, adding that the income is shared by the community. Chao Dro is also happy when travellers come because, “us women used to have to ask our husbands for money but now visitors pay us directly for photos”.

Even though my life is based on tourism, I don’t want them to maintain their traditions just for my survival. I don’t oppose or insist for someone to wear their traditional clothes, it’s their decision. Yonas Mahetemu, tour operator

Scarcity of resources such as water, land and food is in part balanced by the possibility of buying goods thanks to the cash inflow provided by tourism. On the other hand, “travellers are seen as ATMs, a source of easy money,” Miceli points out, a mechanism that creates a cycle of economic dependency that could end up substituting local subsistence mechanisms developed over the course of thousands of years. “The territory is fragmented, the government’s control is sporadic, tourism is rampant, they need money, so it’s easy to fall into a vicious cycle of paying and leaving. Ideally, we should be working on encouraging responsible tourism based on reaching agreements that reflect the tribes’ real needs. Our NGO has the value of raising awareness so that people realise it isn’t right to visit the Omo tribes as if they were items to add to a collection, but it’s desirable to visit fewer of them and spend more time with them”.

There are clear signs that contact with outsiders is radically transforming the tribes’ ways of life. Travellers visit the area to see populations who follow pre-industrial lifestyles but, paradoxically, the sole fact of them being there hastens the tribes’ integration into modern, mainstream society, writes travel journalist Susan Hack. “We must also understand what preserving traditions actually means,” Mattia Grandi comments. “On the one hand, you lose the open-air museum but on the other hand, it’s inevitable. Traditions are such because they change over time through internal and external pressures; they also develop for people to survive in the face of adversity. Maintaining this aspect is of the utmost importance”.

“If we all start wearing your clothes, we’ll lose our traditions”. These words, spoken by Hamer boy Dido Kaffa mirror those of a number of Omo Valley residents who express their desire to preserve their cultures. For example, Chao Dro believes the Arbore have been able to preserve their customs notwithstanding the growth of tourism: in fact, “all women are circumcised when they get married”. The mother of seven children, three of whom girls, offers another example of a practice that is considered a violation of girls’ rights elsewhere but is viewed as a marker of identity here in the Omo Valley.

If it’s truly important that the Omo’s peoples are in control of their future, their choices should be accepted and respected. What they need are the right tools to decide what’s best for them and consciously adapt to the inevitability of change. With the passage of time – and therefore the worsening of climate change, the prolonged impact of the dams and plantations, as well as increased contact with other cultures – this becomes increasingly urgent.

Ethiopia is undergoing radical transformations, also thanks to reforms pushed ahead by Abiy, who “wants the country to develop and leave behind its past of famine and poverty,” in Mahetemu’s words. But the Arbore, Dassanech, Hamer, Kara, Mursi and all the other tribes of the Lower Omo Valley don’t have control over these events. In these uncertain conditions, the question regarding their future remains unanswered. Only time will tell if the pace of life here will continue following that of the river – slow and gentle, and violent and destructive at times – or if change will overwhelm the tribes like an unexpected flood. And if the boy at the beginning of our story will follow his mother’s example by subjecting his children to the same ritual, or if he’ll recount this experience to tell them about a world that no longer exists.

Siamo anche su WhatsApp. Segui il canale ufficiale LifeGate per restare aggiornata, aggiornato sulle ultime notizie e sulle nostre attività.

![]()

Quest'opera è distribuita con Licenza Creative Commons Attribuzione - Non commerciale - Non opere derivate 4.0 Internazionale.

A special report from the Yuqui territory delves deep into the dreams, challenges, joys and sadness of one of Bolivia’s most vulnerable indigenous groups.

The Yuqui people of the Bolivian Amazon fight not only to survive in the face of settlers, logging and Covid-19, but to preserve their culture and identity.

Jair Bolsonaro is accused of crimes against humanity for persecuting indigenous Brazilians and destroying the Amazon. We speak to William Bourdon and Charly Salkazanov, the lawyers bringing the case before the ICC.

Activists hail the decision not to hold the 2023 World Anthropology Congress at a controversial Indian school for tribal children as originally planned.

Autumn Peltier is a water defender who began her fight for indigenous Canadians’ right to clean drinking water when she was only eight years old.

The pandemic threatens some of the world’s most endangered indigenous peoples, such as the Great Andamanese of the Andaman and Nicobar Islands in India.

The Upopoy National Ainu Museum has finally opened. With it the indigenous people of Hokkaido are gaining recognition but not access to fundamental rights.

A video shows the violent arrest of indigenous Chief Allan Adam, who was beaten by two Royal Canadian Mounted Police (RCMP) officers.