South African court dismisses a major lawsuit by 140,000 Zambian women and children against Anglo American for Kabwe lead poisoning. A setback for affected communities enduring the lasting impact of lead contamination.

Extinction is silent, like sand sliding through an hourglass; we barely notice it until it’s too late and have lost what will never return. If someone were to tell us that the only living specimens of a mammal were two females, we would think the species is doomed. How can it survive if it has

Extinction is silent, like sand sliding through an hourglass; we barely notice it until it’s too late and have lost what will never return. If someone were to tell us that the only living specimens of a mammal were two females, we would think the species is doomed. How can it survive if it has exhausted the natural possibility of reproducing itself?

This isn’t a mere hypothesis. After the last male northern white rhino, named Sudan, died of old age, at 45, in March last year, the species survives with only two females, Fatu and Najin. They both live in the Ol Pejeta Conservancy in Kenya and are under 24-hour surveillance to avoid the risk of being killed by poachers.

However, scientists may have found a way to overturn the hourglass and bring these mammals, a subspecies of the white rhino, back from extinction. An international consortium of resarchers called BioRescue, led by Thomas Hildebrandt of the Leibniz Institute for Zoo and Wildlife Research (IZW) in the German capital Berlin, has given us an answer on how to save the northern white rhino from extinction by turning to advanced reproductive technologies.

The group devised a scheme to regenerate the animal’s population through in vitro fertilization, a process in which egg and sperm are fertilized in a lab, therefore outside the animal’s body. For several years before Sudan’s death, scientists at BioRescue had been collecting and freezing semen from northern white rhino bulls, including the last survivor, and testing in vitro fertilization to perfect the technique. The procedure was the result of years of research, development, adjustments and practice.

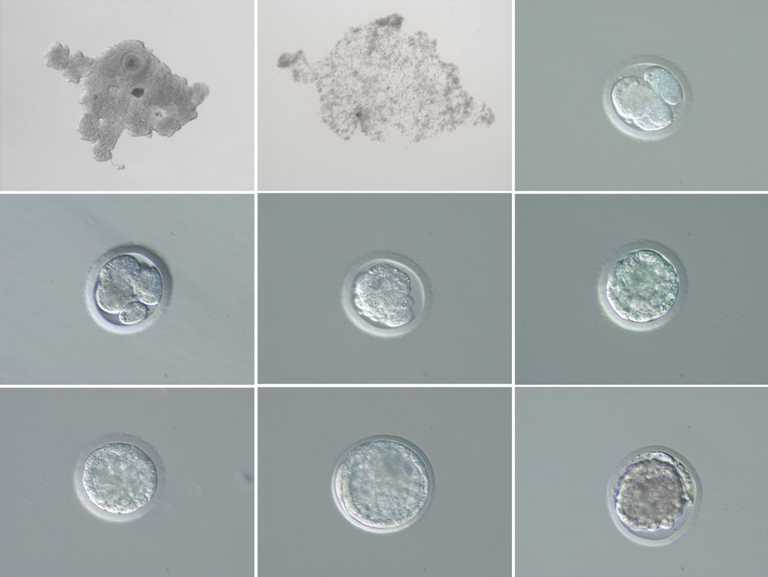

Today, the international consortium of scientists and conservationists has achieved a milestone in assisted reproduction that may be a pivotal turning point in the fate of these magnificent mammals. Using the eggs collected from the two remaining females and frozen sperm from deceased males, they successfully created two northern white rhino embryos. The embryos are now stored in liquid nitrogen to be transferred into a surrogate mother in the near future.

“This is a blueprint that we’re developing with our technology. We only have two females left, so everybody would say, two females? It’s not possible to get the species back from the brink of extinction. But if we succeed, we have a blueprint model that we can use for other species,” Steven Seet, head of Science Communication at IZW, points out.

The consortium includes Avantea, an Italian lab for advanced technologies in animal reproduction based in the northern city of Cremona, which has led the in vitro fertilization process; the Kenya Wildlife Service; Ol Pejeta Conservancy of course; and last but not least, Dvůr Králové Zoo, a safari park in the Czech Republic and one of the best rhino breeders outside of Africa.

At a press conference where the consortium announced the creation of embryos in Cremona on Wednesday September 11th, the Director General of Kenya Wildlife Service, Brig. (Rtd) John Waweru said, “pioneering in vitro embryos of the northern white rhino is a strong testament to what committed partnership can achieve in pushing the frontiers of science to save a creature from extinction.”

In 2014, scientists learned that Fatu and Najin were likely to be unfit for birthing: one has problems in the ligaments of her hind legs, making pregnancy risky, and the other is likely infertile because of cysts and uterine lesions. To bypass this issue, the embryos will be implanted in surrogate mothers of the southern white rhino species, of which there are many more specimens – between 17,212 and 18,915 in the wild.

On 22 August this year, the oocytes were successfully retrieved from anesthetized Fatu and Najin and, during the night, airlifted to Avantea in Cremona for insemination. Extracting their eggs was a tricky process – a procedure that has never been attempted in northern white rhinos before – but ultimately the team counted ten viable oocytes, five from each rhino. At Galli’s lab in Cremona, the team waited about ten to twelve days for the fertilized eggs to develop into embryos.

“We have ten oocytes and the percentage of potential embryos is about 20 per cent, so two embryos is a good average,” says Cesare Galli, founder and director of Avantea, and embryologist famous for cloning a horse for the first time. “It’s the first time we try this procedure with this species so there’s also an unknown factor of timing and protocol to consider”.

One of the unknown factors to consider in the quest to conserve the northern white rhino is perfecting the actual implantation technique of the embryo into the surrogate mothers. Scientists will cryopreserve (i.e. freeze) the embryos until they’re ready to be transferred into the surrogates.

“To implant the embryos successfully, it’s important to choose surrogates who have already proven to be fertile,” Galli told us. “The idea, once the pregnancies are successful, is to have the mothers give birth in Kenya, where the presence of the other females (Fatu and Najin) will help the newborn calves with species imprinting”.

One of the risks is, in fact, that even if the offspring are born, without help from Fatu and Najin the rhino calves might not be able to acquire the behaviour typical of their species. This means that the protection of the last two female rhinos isn’t only fundamental for their own survival, but also because they represent the key to the species’ success in the future.

There are five different rhino species in the world: three in Asia and two in Africa, and two of these have less than 80 animals surviving in the wild. An average of three rhinos are poached for their horn every day across Africa, according to Save the Rhino, a UK-based (and Europe’s largest) rhino charity. This is also true for northern white rhinos, which have been wiped out by poaching and loss of habitat.

This species was once found in abundance throughout southern Chad, the Central African Republic, southwestern Sudan, the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC), and northwestern Uganda. As late as 1960, there were still around 2,360 northern white rhinos, says Save the Rhino, but widespread poaching and civil unrest across the region decimated the species, shrinking the population to only 15 by 1984.

Read more: Mountain gorillas’ survival depends on us

Even though demand for rhino horn in traditional Chinese medicine and dagger handles in Yemen fueled a boom in poaching in the 1970s and 80s, by 2003 the number of northern white rhinos had doubled thanks to international rescue and conservation efforts. The surviving specimens lived in a single population in the eastern DRC’s Garamba National Park at the time. In the following three more years, however, the northern white rhino population was once again exterminated by poaching because, during the Congolese Civil War, harvesting ivory and rhino horn was one method the rebel and militia groups raised funds for their operations. By 2008 the northern white rhino was considered extinct in the wild.

For decades the story of the northern white rhinoceros has been a tale of decline and today the species, with only Fatu and Najin surviving, faces complete extinction. This is why the only hope for these magnificent animals now rests on pioneering assisted reproduction techniques. According to Seet, it’s crucial to save the species because it influences the ecosystem by carrying out an umbrella function: its extinction could cause that of many other animals, insects or plants. “Rhinos have a huge impact on the ecosystem as they’re large browsers and distribute seeds through their faeces. Rhinos are landscape architects and they influence habitat,” says Seet. “We as humans can interrupt that process, invading and destroying it.”

The current efforts scientists are undertaking may well be the animals’ only hope. However, they come with some challenges. Because Fatu and Najin are mother and daughter, and the semen collected in the past years is from only four bulls, the genetic pool is limited and this could create problems for the future development of the species. Eggs can only be collected from the females every three or four months for a maximum of five times, says Galli, and a lack of genetic diversity could hamper the species’ survival. According to Avantea’s founder, this insemination technique could lead to the birth of calves and avoid the species’ extinction, however supporting a healthy northern white rhino population in the long term won’t be easy.

To avoid a “genetic bottleneck”, Seet says, the idea is to develop a second, equally challenging approach based on stem cell research. Using preserved skin samples from twelve northern white rhinos, the researchers hope to produce gametes (egg and sperm cells) which can then be fertilized in vitro to create genetic diversification. Japanese scientists successfully tested this technique on mice, creating a model that produced nine “viable mouse pups” through tissue cells, Seet points out.

Because of the urgency of the project, efforts to revive the northern white rhino should be likely to attract different sources of funding. The consortium encourages that, “the support of additional funding from companies and private donors will help to win our race against time and is a fundamental contribution to save biodiversity and to take environmental responsibility”. At the moment, the consortium is partially funded by the German Federal Ministry of Education and Research (BMBF), and also includes a partnership with the University of Padua in Italy, whose department of Comparative Biomedicine and Food Science participates in the project with special focus on ethics assessments and educational programmes.

“For the egg collection from Najin and Fatu we developed a dedicated ethical risk analysis in order to prepare the team for all possible scenarios of such ambitious procedures and to make sure that the welfare of the animals involved is totally respected”, says Barbara de Mori, the conservation and animal welfare ethics expert from Padua University.

This conservation model could change the game for a number of other endangered rhinos like the Sumatran and Javan rhinos in Indonesia. “There are other species that could benefit (from these techniques), like the Sumatra rhino, where we haven’t reached the criticality of two individuals yet, but even so, only a couple dozen remain, so now should be the time to collect and conserve genetic material,” Galli says. Seet echoes his caution by recalling: “I read a quote from my colleague the other day, he was saying that animals are like textbooks and today…we’re destroying the library of life”.

Conservation efforts to fight extinction shouldn’t commence only once the sand in the hourglass has largely dissipated, but long before. The human impact on many species is too high, and unless we mitigate poaching and loss of habitat due to deforestation, climate change and human settlements, no amount of funding or advances in science will counter their extinction.

Siamo anche su WhatsApp. Segui il canale ufficiale LifeGate per restare aggiornata, aggiornato sulle ultime notizie e sulle nostre attività.

![]()

Quest'opera è distribuita con Licenza Creative Commons Attribuzione - Non commerciale - Non opere derivate 4.0 Internazionale.

South African court dismisses a major lawsuit by 140,000 Zambian women and children against Anglo American for Kabwe lead poisoning. A setback for affected communities enduring the lasting impact of lead contamination.

Controversial African land deals by Blue Carbon face skepticism regarding their environmental impact and doubts about the company’s track record, raising concerns about potential divergence from authentic environmental initiatives.

Only two northern white rhinos remain, and both are females, but scientists have created two new embryos to save the species, for a total of five.

Majuli, the world’s largest river island in Assam State of India is quickly disappearing into the Brahmaputra river due to soil erosion.

Food imported into the EU aren’t subject to the same production standards as European food. The introduction of mirror clauses would ensure reciprocity while also encouraging the agroecological transition.

Sikkim is a hilly State in north-east India. Surrounded by villages that attracts outsiders thanks to its soothing calmness and natural beauty.

Sikkim, one of the smallest states in India has made it mandatory for new mothers to plant saplings and protect them like their children to save environment

Chilekwa Mumba is a Zambian is an environmental activist and community organizer. He is known for having organized a successful lawsuit against UK-based mining companies.

What led to the Fukushima water release, and what are the impacts of one of the most controversial decisions of the post-nuclear disaster clean-up effort?