The Amazon became an alternative classroom during the pandemic. Now, the educational forest in Batraja, Bolivia, lives on to teach children and adults the value of nature.

Bangladesh suffered widespread damage as a result of Cyclone Amphan. Yet the Sundarbans mangrove forest acted as a natural barrier protecting the country from further destruction, as it has done countless times before.

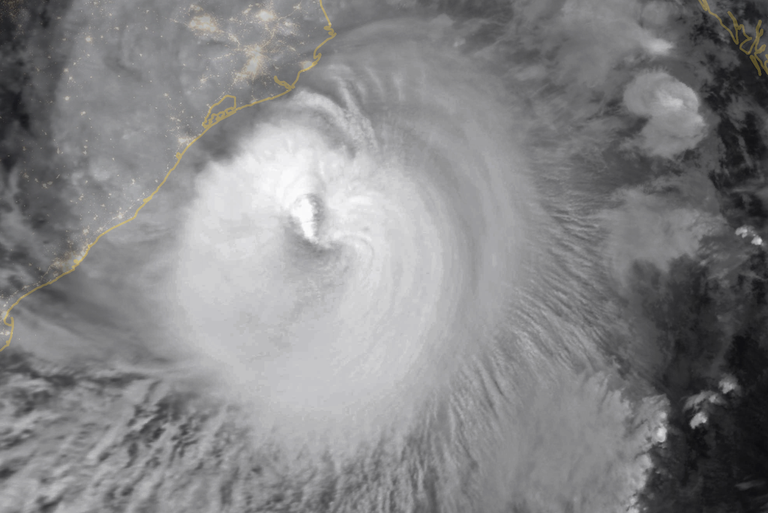

Cyclone Amphan hit Bangladesh on the afternoon of the 20th of May. The severe storm with winds of over 200 kilometres per hour left a trail of destruction in its wake, both in Bangladesh, where 31 people died according to official figures, and the Indian state of West Bengal. It also badly damaged parts of the Sundarbans, a Unesco World Heritage site and the largest mangrove forest in the world, which spreads across Bangladesh and India and is known for its unique flora and fauna. The cyclone broke over 12,000 trees and the forest department has incurred losses in infrastructure worth more than 220,000 US dollars. Yet this irreplaceable ecosystem located in Bangladesh’s Khulna division proved once again be the key saviour for the country, as it absorbed the fury of Amphan much as it has done with similar natural calamities in the past.

Across Bangladesh, the government preventatively evacuated up to two million people including over 700,000 children, who were moved to cyclone shelters in the nine most at-risk districts located in the Khulna and Barisal divisions. There are concerns that those moved to crowded temporary shelters are especially vulnerable to the spread of coronavirus, which has wreaked havoc in Bangladesh. Overall, more than 14 million people in the country live in areas vulnerable to extreme meteorological events, of which five million are children according to UNICEF estimates.

Read more: Coronavirus in Bangladesh, low testing and quarantine set the scene for a humanitarian disaster

Bangladesh’s meteorological department has stated that 26 districts in the south-west and west of the country have been badly affected by Amphan, causing damage to the tune of over a billion dollars. And at least 10 million people across the country have been left without electricity.

In addition, over a thousand kilometres of road and 200 bridges and culverts have been damaged according to the government, as well as 150 kilometres of dams owned by the Water Development Board, with cracks identified in 84 hydroelectric structures. 24 to 36 million dollars will be needed to repair them. Amphan’s fury along the coastal areas of Bangladesh has also affected crops over some 176,007 hectares of land in 17 districts, initial estimates suggest.

On the 15th of November 2007, Cyclone Sidr, with wind speeds up to 260 kilometres an hour, made landfall in southern Bangladesh causing over 3,500 deaths as well as severe damage. But it would have been more devastating still if the Sundarbans hadn’t acted as a safeguard. Similarly, the mangrove forest shielded Bangladesh in May 2009 during Cyclone Aila and last year at the time of Cyclone Bulbul also.

The Sundarbans’ value for the country is impossible to determine in financial terms. The forest is a gift from nature, acting as a wall whenever a severe storm hits Bangladesh. Local people and activists know that “if the Sundarbans weren’t there, the entire Khulna division would be like a desert without trees or human habitation, because the cyclone would bring salty sea water and destroy all vegetation,” in the words of Doctor Reza Khan, eminent wildlife and forest ecology expert.

Cyclone Amphan has battered parts of Bangladesh and eastern India, killing several people and destroying thousands of homes.

Read more: https://t.co/8d5LX6hSrg pic.twitter.com/zkYc0QXJKP

— Al Jazeera English (@AJEnglish) May 21, 2020

Environmental campaigners as well as forest and biodiversity experts have urged the government to halt all economic and commercial activities in and around the mangrove forest. This includes the Maitree Super Thermal Power Plant, a proposed 1,320 megawatt coal-fired power station in Rampal, in Khulna’s Bagerhat district. A partnership between India’s state-owned National Thermal Power Corporation and Bangladesh’s Power Development Board, the joint venture company overseeing it is known as the Bangladesh India Friendship Power Company.

The project, which would cover an area of over 740 hectares, would become Bangladesh’s largest power plant. While the government has defended it by stating that it’s located 14 kilometres north of the Sundarbans’ outer boundary, the plan violates the environmental impact assessment guidelines for coal-based thermal power plants. In 2013, Bangladesh’s Department of Energy approved its construction, but then changed its stance and set 50 preconditions for the project, including it being located outside a 25-kilometre radius from the outer periphery of ecologically sensitive areas.

Given the mangrove forest’s unique biodiversity and key role in protecting the country from cyclones such as Ampham, the hope is that the government will understand its value and act with wisdom and prudence in deciding whether to go ahead with the proposed infrastructure.

Siamo anche su WhatsApp. Segui il canale ufficiale LifeGate per restare aggiornata, aggiornato sulle ultime notizie e sulle nostre attività.

![]()

Quest'opera è distribuita con Licenza Creative Commons Attribuzione - Non commerciale - Non opere derivate 4.0 Internazionale.

The Amazon became an alternative classroom during the pandemic. Now, the educational forest in Batraja, Bolivia, lives on to teach children and adults the value of nature.

Our species took its first steps in a world covered in trees. Today, forests offer us sustenance, shelter, and clean the air that we breathe.

On top of a 2.4 million dollar compensation, the indigenous Ashaninka people will receive an official apology from the companies who deforested their lands in the 1980s.

The tapir was reintroduced into Brazil’s Atlantic Forest, the country’s most at-risk ecosystem. The species can play a key role in the forest’s recovery.

Forests are home to 80 per cent of the world’s terrestrial biodiversity. This year’s International Day of Forests highlights the urgent changes needed to save them.

After a legal battle that lasted two years, Indonesia’s Supreme Court has revoked the permit to mine for coal in the forests of South Kalimantan in Borneo.

The list of human and animal victims of the Australia wildfires keeps growing – one species might already have gone extinct – as the smoke even reaches South America.

Areas where the FARC guerrilla used to hold power in Colombia have faced record deforestation. Farmers cut down trees, burn land and plant grass for cows. Because, “what else can we do for a living here in the Colombian Amazon”? An intimate report from the heart of the felled forest in Caquetá.

Refusing the anthropocentric vision and respecting the laws of ecology is the only way to safeguard the future of our and all other species, Sea Shepherd President Paul Watson argues in this op-ed.