A group of experts in Tokyo suggested pouring radioactive water from Fukushima into the open sea. A marine biochemist explains the consequences of this absurd decision.

Getting people to consume less is important, but it’s not enough. There has to be a cultural shift, and design is likely to have a key role in transforming our approach to plastics.

Using smarter plastics, making them last longer and designing for the future, also in aesthetic terms, with end-of-life in mind. These could be the main precepts defining the role that the world of design can shape for itself in the coming years, forming the basis of an attempt to bring about the cultural change needed to limit the social and environmental impacts of irresponsible plastic consumption.

Read more: Visionaries Marcel Wanders and Ross Lovegrove dialogue on plastics and design

Of course, design alone can’t solve the problem, given the immense consequences of myopic industrial decision-making and inadequate recovery and recycling policies. Of the 90 billion tonnes of raw materials (minerals, fossil fuels, metals and biomass) consumed worldwide each year, only 9 per cent is reused, and in Europe less than a tenth of the 50 million tonnes of plastic produced each year is introduced into a circular economy model.

Yet design can achieve a lot in terms of improving quality by spearheading innovative projects that privilege eco-conscious materials, question their environmental value and encourage adopting new attitudes towards daily consumption.

The ability to bring about new behavioural trends has always been central to the discipline of design, often beginning with the use of new materials, like plastics were in the 1960s. In 1964, when Marco Zanuso and Richard Sapper designed the first ever children’s chair made entirely out of polyethylene – the most common type of plastic – for Italian furniture brand Kartell, the material still needed to build its credibility and reputation. An intelligent and sturdy design based on a single material resulted in an item so well-built that it remained in the company’s catalogue for over twenty years (going out of production only following a change in children’s physical dimensions): the chair has been passed down for generations and is still found in people’s homes today, fifty years on.

Design’s response to the environmental catastrophe caused by plastics is still focused on the realm of behaviour, although today it aims first and foremost to give these materials some social dignity back, so that we may become more conscientious of our choices. This is part of a wider phenomenon that doesn’t only involve plastics. Daphne Stylianou, design researcher and past associate at Material Driven, British platform where designers and startups can showcase their innovations in this field, has coined the term “anthropology of materials” to describe the ever-growing attention that the design community is paying to their social role. This relates to their ability to influence people’s behaviours by promoting a higher degree of care and respect, as opposed to the lack of dignity we usually ascribe to everyday objects.

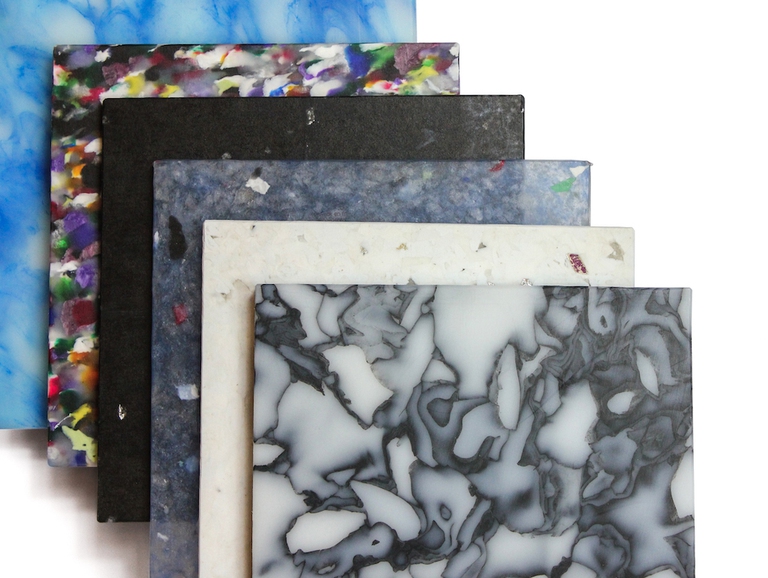

Across Europe, a growing number of innovative projects concerning materials design are finding new and sustainable possibilities for plastics, with the goal of transforming volumes of discarded waste into aesthetic materials, and integrating bioplastics into design strategies for the production of long-lasting products. On both these fronts, the driving motive is the production of beauty supported by the belief that design materials can become ambassadors of the value of conscientious product choices.

Young designers are the ones driving this kind of experimentation, often independently, and by joining forces with engineers and companies, they’re producing materials using semi-industrial techniques. Many are derived from the processing of mixed waste that hasn’t been recovered through industrial or public recycling systems, bought locally and reworked, virtually by hand, to be sold online – sustaining a new upcycling alphabet through which recycled materials are transformed into higher-value objects.

The most recent and probably most interesting of these ventures is ecothylene, a recycled plastic developed by ecoBirdy in Belgium. Its production begins with a process of waste separation based on colours (red, green, yellow, blue, white and clear), which allows for a high degree of control with regards to the resulting products’ aesthetics. The new material, presented in 2018 by ecoBirdy, the Antwerp-based company behind its development, has (for now) been used to create furniture for children: tables, chairs and containers, all pleasantly coloured and with an opalescent finish.

These products are beautiful regardless of the fact that they’re eco-friendly, and they have an important story to tell. The raw materials come from used plastic toys, which, instead of becoming waste, are recovered through an awareness campaign conducted in schools aimed at informing children on the issue of plastic waste and possible solutions. Subsequently, containers are provided to schools, and children and their parents are asked to collect used or broken toys that would otherwise be thrown away. The project, which uses waste from across Europe, is co-financed by the EU’s Competitiveness of Small and Medium-Sized Enterprises (COSME) programme.

The ecothylene project is part of a wide range of schemes that attempt to enhance the value of waste products that wouldn’t otherwise enter waste reduction programmes, giving them a new life.

Supporting upcycling is one of the possibilities for giving plastic a second life, but it’s not the only way to address its impacts. Integrating bioplastics into design projects is equally, if not in some ways more important.

In the over sixty years since their arrival on the productive scene, plastic materials have changed enormously. We often refer to them in the singular – plastic – when in reality this scenario is populated by many different formulas that vary in terms of their origin and performance, and that are in constant evolution. In this shifting universe, “bio” versions of traditional high-performance plastics, i.e. derived from renewable rather than fossil-based sources, such as so-called Green Polyethylene and bio-polyester (PET), are proliferating. However, these are neither biodegradable nor compostable.

The good news is that, while it may seem like an oxymoron given the state of our oceans, today even plastics can be eco-conscious. In recent years, biodegradable and compostable types have been developed and perfected, reaching levels of performance that make them suitable even for specialised uses. Amongst these some are still fossil fuel-based, such as polybutylene succinate (PBS): biodegradable and compostable, it’s derived from bacterial fermentation and its properties allow it to be employed for uses normally reserved for non-biodegradable plastics. Finally, there are biodegradable compounds that, instead of being derived from corn or potatoes (which, if used in massive quantities could cause imbalances in land use), are based on carbon, like Italian-developed polyhydroxyalkanoates (PHAs), created by Lux-on by capturing atmospheric CO2.

Designing bioplastics for the production of durable goods is the aim of companies such as Crafting Plastics!, a European design studio based in Berlin, Germany and Bratislava, Slovakia. Its team spent six years developing Nuatan, a patented new-generation plastic that is based on 100 per cent renewable raw materials and is also completely biodegradable, which the studio uses to create high value-added products. The high-performance material is the result of a longterm interdisciplinary collaboration between Crafting Plastics!, the Slovak University of Technology and Panara, a Slovenian company initially specialised in polyethylene film. Since 2006, Panara has been investing in bioplastics and produces several types based on PHB (polyhydroxybutyrate, a biodegradable plastic made naturally with bacteria), PLA (polylactic acid, a polymer derived from biomasses) or biodegradable and compostable polyester.

Composed entirely of plant-based biopolymers made of PLA and PHB obtained from natural sources like corn or potato starch, Nuatan can resist to temperatures of over 100°C and has a programmable lifespan ranging from one to fifty years, depending on the mixture. When put into an industrial composter, the material biodegrades in water, CO2 and biomass. The second generation currently being developed will also biodegrade in domestic composts, soil and ocean water. The new material can be injection moulded and 3D printed, or “blown” like traditional plastics. It was developed and fine-tuned with the precise aim of accelerating the transition to a circular economy, optimising the lifecycle from the moment of production all the way to the final dismantling of various products, including consumer electronics.

What about recyclability? Important steps are also being made in this field: an Italian startup, Direct 3D, has perfected and patented a special extrusion head that allows for 3D printing from granules, powder or mixed shavings, rather than just classic filaments. This paves the way for using recycled plastics even in small-volume productions.

Also, on a larger scale, Dow Chemical, one of the world’s principle plastic manufacturers, recently announced that it has developed a way of using recycled plastic in the production of alternative asphalt. And in the Netherlands the Plastic Road project is currently being tested on cycling lanes in Rotterdam, with the aim of creating roads that integrate cabling and water distribution systems entirely from plastic waste recovered from the oceans and diverted from incineration plants.

Hence, the challenge is open.

Siamo anche su WhatsApp. Segui il canale ufficiale LifeGate per restare aggiornata, aggiornato sulle ultime notizie e sulle nostre attività.

![]()

Quest'opera è distribuita con Licenza Creative Commons Attribuzione - Non commerciale - Non opere derivate 4.0 Internazionale.

A group of experts in Tokyo suggested pouring radioactive water from Fukushima into the open sea. A marine biochemist explains the consequences of this absurd decision.

The decline in grey and humpback whales in the Pacific and Atlantic Oceans has been traced to food shortages caused by rising ocean temperatures.

The United Nations has launched a major international alliance for ocean science, undertaking a mission close to all our hearts.

By recovering clothes discarded in the West, Togolese designer Amah Ayiv gives them new life through his high fashion creations.

The cargo ship that ran aground off the coast of Mauritius on 25 July, causing incalculable damage, has split in two and its captain has been arrested.

All catwalks in July will be broadcast online: after Paris, it’s Milan Digital Fashion Week’s turn. And the biggest beneficiary is the environment.

The largest coral reef in the world is severely threatened by climate change, but researchers are developing strategies that could contribute to saving the Great Barrier Reef.

The book Fashion Industry 2030 aims to contribute to reshaping the future through sustainability and responsible innovation. An exclusive opportunity to read its introduction.

Seychelles have extended its marine protected area, which now covers over 400,000 square kilometres, an area larger than Germany.