A special report from the Yuqui territory delves deep into the dreams, challenges, joys and sadness of one of Bolivia’s most vulnerable indigenous groups.

The Upopoy National Ainu Museum has finally opened. With it the indigenous people of Hokkaido are gaining recognition but not access to fundamental rights.

The Upopoy National Ainu Museum and Park in Shiraoi, Hokkaido, the northern-most main island of Japan, finally opened to visitors on the 12th of July after months of delays due to the coronavirus pandemic. Built on the banks of the scenic Lake Poroto, the Upopoy has been created in an effort to promote knowledge and understanding of the Ainu people, the indigenous inhabitants of Hokkaido.

Also known as the Symbolic Space for Ethnic Harmony, this is Japan’s first national museum to diverge from the display and celebration of explicitly “Japanese” culture. Upopoy, which in Ainu language means “singing in a large group”, intends to act as the centre of Ainu culture and provide a space in which to learn about the rich variety of customs and traditions. A heritage that has been threatened to the brink of extinction due to over a century of colonial assimilation and discrimination policies by the Japanese government, which only recently passed the 2019 Ainu Recognition Bill: the first legal acknowledgement of the Ainu as the indigenous people of Japan, with their own language, beliefs and customs.

In the era of Black Lives Matter, Me Too and the global struggle for the protection of indigenous rights the Japanese government has felt increasing pressure to put Ainu culture on the map. Meant to open in concomitance with the 2020 Tokyo Olympic Games, the Upopoy has cost over 182 million US dollars and has been advertised extensively. Posters and videos of Ainu people donned in traditional robes, with eye-catching, brightly coloured geometrical patterns, have featured across the country and beyond. From the Tokyo Metro to an exhibition in London, the Upopoy’s opening has been promoted heavily and, prior to the outbreak of Covid-19, the target was to attract one million visitors a year. A clear recognition of the Ainu cultural centre’s potential as a tourism asset.

“The function of the museum is educational and tries to communicate indigenous Ainu culture. It can provide a space to correct some misled views about Ainu people”, explains Mark Winchester, Associate fellow at The Foundation for Ainu Culture. The complex is spread across 100,000 square metres of land, hosting three distinct areas for the display and promotion of Ainu culture. Firstly, the National Ainu Museum building, which features exhibitions in a gargantuan, modern and slickly designed building. Secondly, an outdoor National Ethnic Harmony Park dotted with reconstructed traditional villages, kotan, which house dwellings known as cise, and areas designated for open-air ceremonies and light shows. Finally, the most debated element, a Memorial Site, which hosts a collection of human Ainu remains that have been taken from burial sites over the course of the centuries for research purposes and are now to be stored at the Upopoy.

To date, over 1,600 human remains have been excavated from burial grounds across Hokkaido. Rarely engaging with local communities in obtaining their free, prior and informed consent, this has caused considerable resentment among Ainu communities. For decades Japanese and international researchers have kept these remains for research, storing them in university repositories. In the build-up to the opening of the museum, Ainu people were given the chance to apply for the ancestral repatriation of the exhumed remains, with all those left unclaimed to be moved to the Upopoy.

However, a number of communities have since complained that the application process provided significant barriers and that the transferral to the Upopoy amounts to yet another instance of forced displacement. “Ainu ancestors were forcibly relocated from their birthplaces to new settlements, then those buried in these new places were excavated without Ainu consent and kept in universities,” claims Hiroshi Maruyama, founder of the Centre for Environmental and Minority Policy Studies (CEMiPoS). “Now, these ancestral remains are collected at the memorial building in Upopoy. This amounts to the third forcible relocation of Ainu people”.

This issue has been a hotly contested subject and many communities and activists continue to voice their opposition to the transferral of human remains to the Upopoy, indicating that this benefits Japanese researchers and not the Ainu themselves.

The robbery of sacred burial grounds is just one aspect of the discrimination and repression suffered by the Ainu, who were subject to assimilation policies for over a century beginning in the Meiji era (1868-1912). The stamping out of Ainu culture not only sought to repress customs and practices but also render access to traditional means of livelihood illegal.

Laws against fishing and hunting were first introduced as far back as 1876 and have never been repealed. Furthermore, the 1899 Former Aborigines Protection Act consolidated assimilation policies starting with its very wording, where “former” was meant to imply that the Ainu identity had now merged with the modernising Japanese one. A systematic process of cultural annihilation whose effects are particularly evident in the evolution of the Ainu language, which has all but disappeared.

“As a result of assimilation policies, very few people are speaking Ainu these days and those who were completely raised in the Ainu language passed away in the mid 20th century,” explains Jeffry Gayman, Professor at the Department of Intercultural Education at the Faculty of Media and Communications at the University of Hokkaido, who was also involved in a major survey on the status of transmission of the Ainu language in 2012. “There are possibly only five native speakers still remaining and the people who do speak Ainu picked it up passively by being around a grandparent. Most of these people are now in their late eighties or nineties”.

Following post-World War Two reforms, the Japanese government engaged in a gradual process of reversing its racist policies based on eugenics and the desire to portray the nation as a uniform ethnic pot. In 2019, decades of legal reform reached their highpoint with the Ainu Recognition Bill.

The Upopoy is an integral part of this process and in 2009 the Council for Ainu Policy Promotion (chaired by Japan’s Chief Cabinet Secretary) stated that a “symbolic space for ethnic harmony” was key to a policy based on the recognition of the Ainu as an indigenous people. However, this new approach hasn’t come without controversy. “The Upopoy is the centrepiece of the new Ainu policy and is actually referred to in the legislation of 2019 as the new hub of Ainu cultural revitalisation,” Gayman points out, “which in terms of indigenous self-determination and community development is ironic seeing as the Japanese state has stripped the Ainu people of their lands, natural resource rights, education systems and political, social and economic customs. To now put forth the notion that Ainu culture, as defined by the Japanese state, can only be revitalised through a museum is ironic, to say the least”.

Ainu activist Shikada Kawami, former curator of the Asahikawa City Museum, released a statement in the days prior to the museum’s opening summarising many of the grievances levelled at it: “Upopoy looks like another instance of the Japanese exerting their power over the Ainu. Stolen Ainu human remains have been collected in the memorial building there. The collection benefits Japanese researchers but doesn’t alleviate the profound sorrow held by many grieving families. Some Japanese people blame us Ainu for wanting more besides Upopoy. In other words, they say that we should be satisfied and grateful for Upopoy. I don’t know how many Ainu are aware of the degree to which they are still exploited and discriminated against. I think we should study our culture, our language, our history and legitimate human rights more”.

Activists accuse the Japanese government of portraying a static image of the Ainu, whose cultural identity is being appropriated for its appealing commercial pull, whilst ignoring the issue of legal rights so that “protection has emerged synonymous with commodification,” continues Maruyama.

In particular, the failure to provide a set of rights to land, fishing and hunting has been particularly contentious as it confines “Ainu culture” to a projection of the past rather than granting access to the resources needed to actually live as an Ainu in the present. “Ainu culture isn’t limited to language or ceremonies or dance,” explains Ainu activist Tahara Ryoko, chairperson of the Ainu Women’s Association. “It is Ainu life itself. Whatever happens every day within the household is Ainu culture”. To promote an apolitical notion of Ainu culture whilst sidelining political and economic rights is problematic. Particularly as Ainu customs, beliefs and ceremonies are intrinsically linked to nature and the land on which they have lived for centuries.

Ainu activists indicate that recognition of indigeneity must go hand in hand with granting of legal rights. “Unfortunately, the Ainu are losing their connection to their lands and water because they have been prohibited from hunting and fishing,” explains Maruyama. “This limits Ainu culture to song, dance, embroidery and artefacts: products”.

This is especially apparent in the case of Satoshi Hatakeyama, the 77-year-old chairman of the Monbetsu Ainu Association, who has been subject to a criminal investigation for catching salmon in the Mobetsu River without the Hokkaido government’s permission. “Salmon fishing is something that our ancestors have continued doing for a long, long time,” the Ainu elder told reporters at a news conference. “If the central government recognises Ainu as an indigenous people, then it must seriously think about the return of and compensation for land and resources.”

“The fishing rights of indigenous peoples are guaranteed by international law,” echoes Maruyama. “The government should be rushing to put the recovery of these people’s rights into legislation but instead the issue hasn’t even come up as a topic of debate. Hatakeyama’s actions were meant to present the problem publicly and were out of necessity.”

Undeniably the Upopoy has helped put the Ainu on the national and international map, which can be understood as a step in the right direction. For many, both Ainu and non, it is a source of pride and satisfaction. A modern facility where countless people can learn about Ainu culture and Ainu people themselves can practice some of their traditions, passing them on to the new generations. However, for others, it is the logical continuation to assimilation policies, whereby symbolic recognition has been granted without any of fundamental rights for true cultural preservation. Without these rights, some Ainu see it as impossible to maintain their culture and identity and fear that what it means to be Ainu will remain embedded in static images of the past, commodified and sold as little more than stereotypes and false representations.

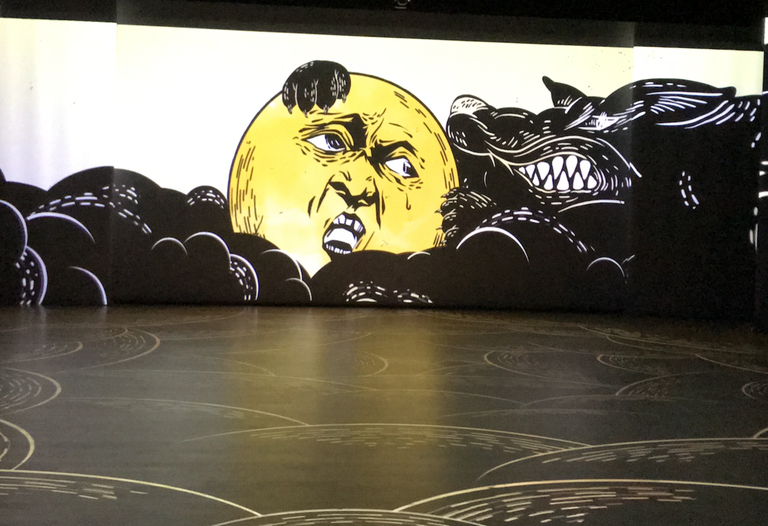

Watching the mesmerising light show at the Upopoy Museum’s opening ceremony, where traditional folk tales have been turned into captivating anime cartoons and traditional Ainu music is adapted to fast-paced electronic beats blasting from state-of-the-art speakers, it is hard not to be impressed. At the same time, the question lingers: is this the manifestation of an evolving Ainu cultural identity or simply its subjugation to the dominant narrative?

The truth, as always, probably lies somewhere in between.

Siamo anche su WhatsApp. Segui il canale ufficiale LifeGate per restare aggiornata, aggiornato sulle ultime notizie e sulle nostre attività.

![]()

Quest'opera è distribuita con Licenza Creative Commons Attribuzione - Non commerciale - Non opere derivate 4.0 Internazionale.

A special report from the Yuqui territory delves deep into the dreams, challenges, joys and sadness of one of Bolivia’s most vulnerable indigenous groups.

The Yuqui people of the Bolivian Amazon fight not only to survive in the face of settlers, logging and Covid-19, but to preserve their culture and identity.

Jair Bolsonaro is accused of crimes against humanity for persecuting indigenous Brazilians and destroying the Amazon. We speak to William Bourdon and Charly Salkazanov, the lawyers bringing the case before the ICC.

Activists hail the decision not to hold the 2023 World Anthropology Congress at a controversial Indian school for tribal children as originally planned.

Autumn Peltier is a water defender who began her fight for indigenous Canadians’ right to clean drinking water when she was only eight years old.

The pandemic threatens some of the world’s most endangered indigenous peoples, such as the Great Andamanese of the Andaman and Nicobar Islands in India.

A video shows the violent arrest of indigenous Chief Allan Adam, who was beaten by two Royal Canadian Mounted Police (RCMP) officers.

On top of a 2.4 million dollar compensation, the indigenous Ashaninka people will receive an official apology from the companies who deforested their lands in the 1980s.