At the dawn of a new era, women in Japan still face old challenges: they’re paid less than men and struggle to scale the professional ladder. How can the impasse be broken?

Sharia is the Islamic canonical law based on the teachings of the Koran (Qur’an) and the Prophet Muhammad: a set of disciplines and principles that govern the behaviour of a Muslim towards others including with regards to investments or financial services. Sharia explains the Islamic concepts of money and capital, the relationship between risk and profit, and the social

Sharia is the Islamic canonical law based on the teachings of the Koran (Qur’an) and the Prophet Muhammad: a set of disciplines and principles that govern the behaviour of a Muslim towards others including with regards to investments or financial services. Sharia explains the Islamic concepts of money and capital, the relationship between risk and profit, and the social responsibilities of financial institutions and individuals in detail.

Based on this philosophy, Sharia-compliant instruments and techniques have been developed and used by Islamic finance units and customers for financial activities worldwide. Central to Islamic finance is the concept that money itself has no intrinsic value, it is simply a medium of exchange. The two most important components of the Islamic financial world are banking services and the sukuk market – the Islamic equivalent of the bond market. Other services include leasing, equity markets, investment funds, insurance (Takaful), reinsurance (Retakaful) and microfinance.

A Muslim isn’t allowed to benefit from lending or receiving money. In addition, paying or receiving of interest is forbidden (riba), financial activities involving excessive uncertainty shouldn’t be engaged in (gharar) and prohibited (haram) sectors can’t be invested in. These are the cornerstones of Islamic finance.

Riba is a concept in Islamic banking that refers to charged interest and is forbidden under Sharia law because it is thought to be exploitive. Riba creates social injustice because lenders requiring interest on loans tend to profit from the weak position of borrowers. In an Islamic mortgage, for instance, a bank doesn’t lend money to an individual who buys a property; instead, it buys the property itself. The customer can then either buy it back from the bank at a higher price, paid in instalments (murabahah) or make monthly payments to the bank comprising both a repayment of the purchase price and rent until they own the property outright (ijara). Similarly, a holder of sukuk hasn’t technically lent the issuer money; instead, they own a nominal share of whatever the money was spent on and derive income not from interest but either from the profit generated by that asset or rental payments made by the issuer. At the end of the sukuk’s term the issuer returns the principal to the investor by buying shares in the asset.

Gharar is an Arabic word that is associated with uncertainty, deception and risk and is prohibited under Islam as there are strict rules against transactions that are highly uncertain (similar to joker123 gambling). This includes the prohibition of conventional financial practices like: forms of insurance, such as the purchase of premiums to insure against something that may or may not occur; short selling, the sale of a security that is not owned by the seller; speculative trading, which is trading without the intention of actually obtaining the underlying commodity; and derivatives, a contract between two parties that derives its value or price from an underlying asset like stocks, bonds or commodities.

Not very different from the concept of socially responsible investing (SRI), Sharia investing excludes companies that are prohibited by Islamic law (haram) by not investing in them. These so-called sin stocks include companies which derive income from the sale of alcohol, pork products, pornography, gambling, military equipment or weapons.

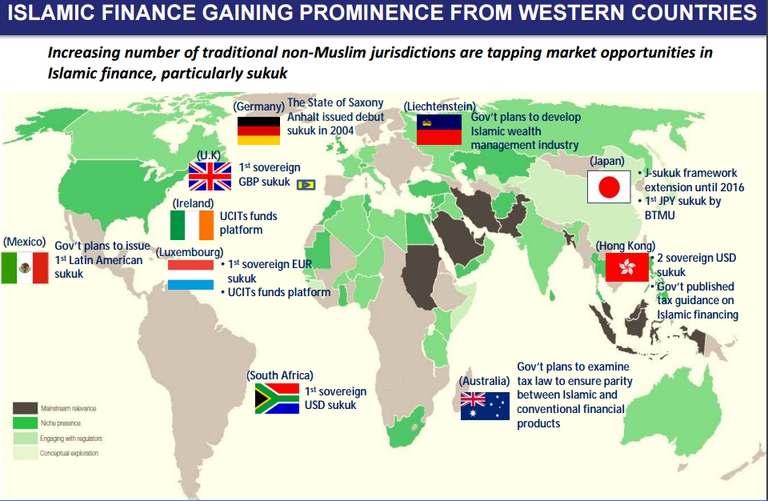

Sharia investing gained popularity in the mid-1970s, coincident with and in response to the accumulation of tremendous oil wealth in Islamic states, which fuelled interest in and demand for Sharia-compliant products and practices. The Islamic finance market stands at USD 2 trillion in assets based on 2015 assets disclosed by all Islamic Finance institutions along with sukuk and Islamic funds (projected to grow to around 3.5 trillion by 2021), according to the State of the Global Islamic Economy Report 2016/2017. Islamic banking outperformed conventional banking, increasing its penetration rate above 15 per cent in the Middle East and Asia. Sukuk issuances also increased twenty times to reach USD 120 billion in 2013, with new issuances in Africa, East Asia and Europe.

According to Sharia, money itself isn’t considered equal to wealth but is a means through which we can create a system of production and trade, generating social impact in sectors such as knowledge, health, education and infrastructure. Islamic finance has emerged as an effective tool for financing development worldwide, including in non-Muslim countries, according to the World Bank. Moreover, since Sharia investment emphasises asset-backed financing and risk-sharing, it provides alternative sources of financing for small and medium-sized enterprises (SME), as well as investment in public infrastructure. For example, Malaysia has used sukuk to build roads, airports and other large infrastructure projects; the Islamic Development Bank has lent USD 150 million through Sharia-compliant facilities for the new Lekki port in Nigeria. This is especially important as infrastructure needs in developing countries will continue to rise over the next decade and these are struggling to be met by public investments or traditional bank funding. The emphasis on tangible assets ensures that the industry supports only transactions that serve a real purpose, thus discouraging financial speculation.

Due to the ethical basis of Islamic finance and poor performance of conventional banks following the financial crisis, Sharia investment is attractive even to non-Muslims looking for ethical investments or fair financial products. For example, in 2013 Britain became the first western country to issue sovereign sukuk; the GBP 200 million (USD 322 million) sale attracted orders of GBP 2.3 billion.

Since the onset of the 2008 financial crisis, the Islamic finance industry has continued to expand at a rate of 17 per cent per year, helping to strengthen financial stability. It also helps promote financial sector development and broadens financial inclusion. Of the 1.6 billion Muslims (around a quarter of the global population) in the world, only 14 per cent use banks, with Sharia-compliant assets making up only around 1 per cent of the world’s financial assets. Considerable potential exists for expanding Islamic finance which is held back by a lack of awareness of what it offers. Even in countries where Islamic banking has a strong foothold, such as the Gulf states or in Southeast Asia, its share rarely accounts for more than one third of the market.

Despite this, Islamic finance is still in its early stages of development and needs to address several challenges. Currently, it is less profitable than conventional banking. A 2014 E&Y report finds that shareholder returns are 20 per cent lower as a result of higher costs and operational inefficiencies. Islamic banks tend to be smaller, making it hard to achieve economies of scale. Furthermore, they’re relatively poor at cross-selling (selling a different product or service to an existing customer) with an average of 2.1 products per customer compared to 4.9 products per customer in conventional banks. Sukuk financing also has not taken off outside Malaysia due to the lack of stable regulatory frameworks and an economic environment encouraging of it.

There is also far less standardisation in available products because of banks’ and jurisdictions’ different interpretations of what is acceptable under Sharia law. For example, Goldman Sach‘s attempt at entering the market failed amid claims its proposed sukuk was non-compliant. Indonesia scaled back its issuance of one type of sukuk due to similar complaints.

This has led to calls for greater international standardisation, in turn leading to the creation of the Islamic Financial Services Board, which issues both religious and prudential guidance (playing the same role as the Basel Committee does for conventional banks).

Islamic banks have tremendous scope to keep growing and to become more than a niche market, but they must compete with the conventional banks to play their expected part in supporting the development of emerging economies and financially underserved populations.

Siamo anche su WhatsApp. Segui il canale ufficiale LifeGate per restare aggiornata, aggiornato sulle ultime notizie e sulle nostre attività.

![]()

Quest'opera è distribuita con Licenza Creative Commons Attribuzione - Non commerciale - Non opere derivate 4.0 Internazionale.

At the dawn of a new era, women in Japan still face old challenges: they’re paid less than men and struggle to scale the professional ladder. How can the impasse be broken?

Inequality has increased anywhere in the world despite substantial geographical differences, with the richest 1% twice as wealthy as the poorest 50%. The results of the World Inequality Report 2018.

AXA Investment Managers, a France-based investment service provider, has pledged to divest 165 million euros (175 million dollars) of its fixed-income portfolios and 12 million euros (13 million euros) of equities portfolios as a result of its new coal policy. It announced that it won’t invest in companies that derive more than 50 per cent of their

We talk to Samir de Chadarevian, an expert in sustainable development, philanthropy, impact investing and social innovation.

The global gender gap or index has widened, the 2017 World Economic Forum report shows. In view of the International Day for the Elimination of Violence against Women, we analyse how these phenomena are sadly related.

We can learn a lot from philanthropists and families investing their money for the future of all of us. We talk about this with Gamil de Chadarevian, founder of GIST Initiatives.

How do wealthy families invest their capital? Fortunately, impact investing is an increasingly common choice. An anticipation of some of the most important findings.

All companies aim to profit, but some of them are doing something for the society. They’re called benefit corporations.

More and more wealthy families care about our Planet. Data emerged from the Investing for Global Impact prove this.