Mountain areas are home to around 1 billion people and provide goods and services. This is why the protection of healthy mountain ecosystems has become a must. The op-ed by FAO’s Mountain Partnership Secretariat.

Inequality has increased anywhere in the world despite substantial geographical differences, with the richest 1% twice as wealthy as the poorest 50%. The results of the World Inequality Report 2018.

In the last few decades, inequality has increased everywhere in the world. This is not only one of the causes of poverty and social conflict, but also one of the elements that form the contemporary economic system: globalized capitalism.

This message is conveyed by the 2018 World Inequality Report that was presented in mid December in Paris, France. It’s the first document that discusses this phenomenon on a global scale: the 300-page text was created by approximately 100 researchers from around the world and developed on an enormous database that was made public and therefore available for anyone who wishes to study the analysis in depth. The objective is to present a snapshot of the current situation, comprehend the changes that brought us to it and make hypotheses on possible future scenarios.

British economist John Maynard Keynes published The General Theory of Employment, Interest and Money in 1936 explaining that capitalism was not only unable to guarantee sufficiently low rates of unemployment, but had also caused “an unequal distribution of arbitrary wealth”. This consideration is even more true and current 80 years later. In fact, economist Lucas Chancel, the main coordinator of the report, said that “on a global level, the top 1 per cent has pocketed twice as much of the economic growth as half of the bottom 50 per cent”.

The researchers working on the project have explained that “economic inequality is widespread and to some extent inevitable. It is our belief, however, that if rising inequality is not properly monitored and addressed, it can lead to various sorts of political, economic, and social catastrophes“. Especially in countries where the gap between the rich and poor is wider.

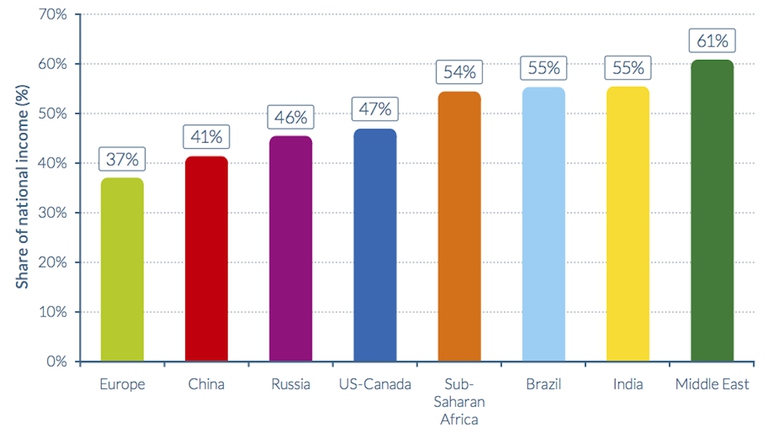

The World Inequality Report shows that the disparity in wealth distribution varies significantly from one region to another. In Europe, 37 per cent of the national revenue is pocketed by the top 10 per cent, 41 per cent in China, 46 per cent in Russia, 47 per cent in North America and around 55 per cent in sub-Saharan Africa, Brazil and India. The highest value can be found in the Middle East, with 61 per cent.

Data on the development of African economies (supporting the hypotheses expressed by Branko Milanovic’s work, titled Global inequality: a new approach for the age of globalization, where he theorizes the existence of unavoidable waves of inequality) are especially alarming. The disparity that was registered in the distribution of wealth produced in numerous countries within the continent could in fact be a recipe for disaster if combined with the strong demographic growth that is predicted to take place in the same area. Today, Africa hosts 17 per cent of the global population, but this figure is expected to hit 26 per cent in 2050. Between 1993 and 2013, in Italy, the poorest 90 per cent of the population lost 15 per cent of their wealth (from 60 to 45 per cent). Whilst the top 10 per cent gained the remaining 55 per cent.

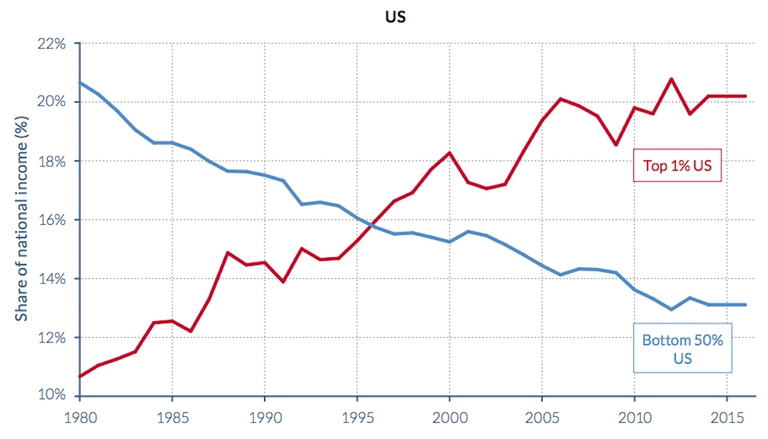

Trends from the last few years show a generalised increase of inequalities: from 1980 to 2016, they have grown especially in the United States, China, India and Russia. In Europe too, but less so. The portion of wealth held by the top 1 per cent has increased from 10 to 12 per cent in the old continent. On the other hand, the figure has grown from 22 per cent in 1980 to 39 per cent in 2014. The report states that “the income-inequality trajectory observed in the United States is largely due to massive educational inequalities, combined with a tax system that grew less progressive”, focal point of the liberalist economic theories.

In China and Russia, the amount of wealth held by the top percentage of the population has gone from 15 to 30 per cent in China and from 22 to 43 per cent in Russia. In a way this can be seen as good news: the gap between Europe and other countries shows that if they want to, institutions possess the means to limit inequalities. Lowering taxes using progressive rates, introducing transfers that favour the poor, imposing a minimum wage and offering more public services are a few examples of effective methods to contrast the structural tendencies of capitalism that widen the gap between the rich and the poor. A tax on financial transactions is another example.

The report underlines that the increase in inequalities grew parallel to another phenomenon: the decrease of wealth owned by the public compared to private wealth. The study explains that “there has been a general rise in net private wealth in recent decades, from 200-350 per cent of national income in most rich countries in 1970 to 400-700 per cent today.” And the 2008 financial crisis “didn’t invert the trend”.

In the last few decades, in China and Russia, the percentage of public property went from 60-70 per cent to 20-30 per cent. “This arguably limits government ability to regulate the economy, redistribute income, and mitigate rising inequality. The only exceptions to the general decline in public property are oil-rich countries with large sovereign wealth funds, such as Norway.”

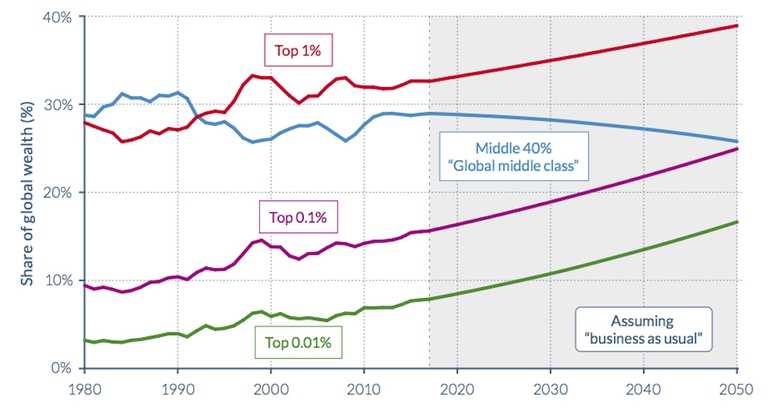

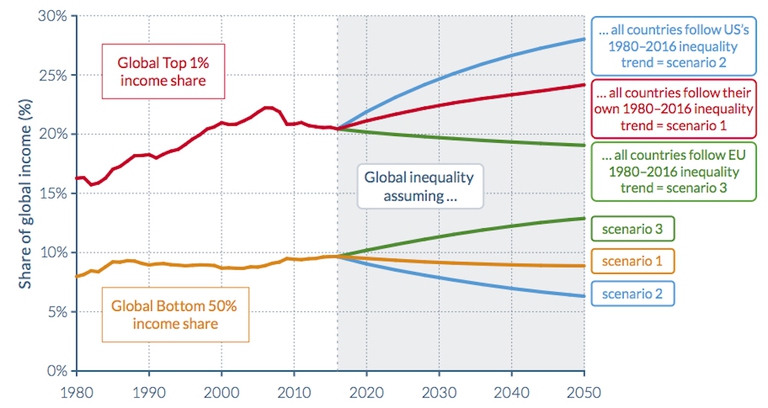

The report also includes some projections for years to come: “The continuation of past wealth-inequality trends will see the wealth share of the top 0.1 per cent global wealth owners (in a world represented by China, the EU, and the United States) catch up with the share of the global wealth middle class by 2050”. Things will be even worse if the world adopts the North American liberalist approach. On the other hand, the gap will shrink if we opt for European model.

This will all be accompanied by drastic set backs in terms of poverty: the average yearly income of an adult who is part of the poorest 50 per cent of the world population is 3,100 euros. In 2050 this figure will rise to 9,100 if the European model is adopted, and only 4,500 if the American one is followed.

Siamo anche su WhatsApp. Segui il canale ufficiale LifeGate per restare aggiornata, aggiornato sulle ultime notizie e sulle nostre attività.

![]()

Quest'opera è distribuita con Licenza Creative Commons Attribuzione - Non commerciale - Non opere derivate 4.0 Internazionale.

Mountain areas are home to around 1 billion people and provide goods and services. This is why the protection of healthy mountain ecosystems has become a must. The op-ed by FAO’s Mountain Partnership Secretariat.

AXA, one of the world’s biggest financial services companies, is dumping investments in tar sands and ending insurance for controversial oil pipelines, taking fossil fuel divestment to new heights.

We talk to Samir de Chadarevian, an expert in sustainable development, philanthropy, impact investing and social innovation.

We can learn a lot from philanthropists and families investing their money for the future of all of us. We talk about this with Gamil de Chadarevian, founder of GIST Initiatives.

After Pantelleria, Italy in 2014, the Republic of Malta in 2015, and Gran Canaria, Spain in 2016, this year the Italian island of Favignana, off the coast of Sicily, will host the fourth edition of the Greening the Islands International Conference on the 3rd and 4th of November. The event marks an important opportunity to tackle the topic of

How do wealthy families invest their capital? Fortunately, impact investing is an increasingly common choice. An anticipation of some of the most important findings.

All companies aim to profit, but some of them are doing something for the society. They’re called benefit corporations.

More and more wealthy families care about our Planet. Data emerged from the Investing for Global Impact prove this.

In the next few months LifeGate will host a series of in-depth analyses on philanthropy and impact investing. This section is supported by Investing for Global Impact, a global research published by The Financial Times in partnership with GIST (Global Impact Solutions Today) and with the support of Barclays. Why philanthropy and impact investing, together In